Are cracks starting to appear in the once white-hot M&A market for independent RIAs?

Despite a plummeting stock market and signals from the Federal Reserve that it may risk plunging the economy into a recession in order to cool inflation, mergers and acquisitions in the still highly fractured independent wealth management space continued at a record pace.

Year to date through the third quarter, there have been 203 RIA deals completed, up 23% from the first nine months of 2021, according to the latest DeVoe RIA Deal Book. DeVoe & Co. predicts total 2022 transactions will top last year’s tally of 241 deals by a range of 12% to 20%.

Yet deals in the space may be a lagging economic indicator. Big RIA buyers are not immune to market conditions, industry observers say. The underlying economics are bound to put pressure on firms’ balance sheets, and while it remains to be seen how that changes the landscape for deal-makers, few doubt it will.

Many active RIA acquirers finance deals with debt. And with the Federal Reserve raising interest rates, financing costs are going up at a time when revenues, still largely a percentage of assets under management, are decreasing. These acquirers are dealing with inflation-challenged margins, falling market valuations and nervous lenders, whose non-performing loan books are starting to grow.

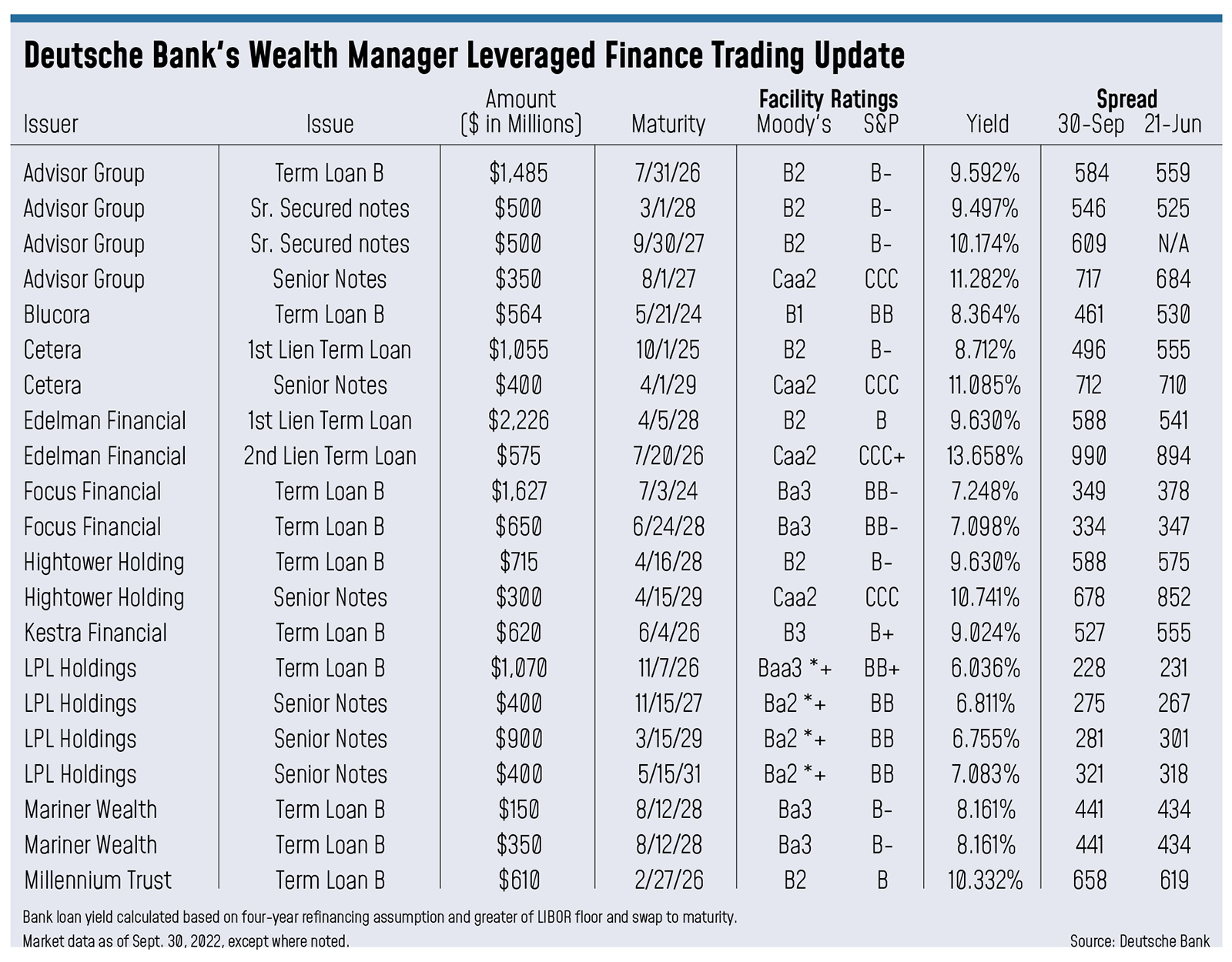

If these firms continue to do deals, not only will their future borrowing costs increase but also the costs of servicing their current debt. Yield spreads in the bonds of many active wealth management acquirers—already in or near junk status—are widening, a sign the market is requiring more compensation to hold their debt.

Higher financing costs and lower revenue make lenders more skittish, and lead to more restrictive covenants on loans, less frenzy in the market and fewer deals.

“It’s a simple rule of banking that if the cash don’t flow, the loan don’t go,” said Mark Tibergien, a consultant and the retired CEO of Pershing Advisor Solutions.

“The concern is the ability to repay. You can see it with some firms seeking equity through the public markets, or trying to and not succeeding, as a way to rebalance their balance sheet,” he said. “I wouldn’t say [lenders have] turned off the spigot, but they have made access to it a little bit more of a challenge, either through pricing or through other qualifications that they’re looking at.”

Matthew Crow, president of Mercer Capital, a business valuation and financial advisory services firm, said investor sentiment in publicly traded RIAs shifted negative last November when it became clear the Federal Reserve was going to raise interest rates.

“Acquisition activity from the publics has been muted this year, probably a consequence of their sagging stock prices,” Crow said.

Focus Financial’s stock price is down some 47% year to date (as of Oct. 11). CI Financial, another active acquirer in the U.S. RIA market, stock price declined nearly 57% this year. That far outpaces the broader 19% loss in the S&P 500 financial sector.

Privately held companies looking to access public markets seem to be in retreat. Dynasty Financial Partners, the St. Petersburg, Fla.–based services platform for independent advisors, filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission in January for an IPO; last April, CI said it would sell up to 20% of its U.S. wealth management business via an IPO, using the proceeds to pay down the debt that helped fuel the spending binge; in September 2021, RIA Tiedemann Advisors made a deal with Cartesian Growth Corp., a special purpose acquisitions company (SPAC), to merge with British money manager Alvarium Investments and go public last month.

“None have happened, and none are likely,” Crow said. These acquirers are not required to disclose their financials, “and in a year like this, I’m sure they’re grateful for it.”

Inflation is a double-edged sword for RIAs, he said. “Inflation is positively correlated with the cost of doing business … and negatively correlated with asset values.” Beyond financing, labor costs are rising, hitting as much as 75% of an RIA’s operating budget.

On the other side, revenue for most RIAs is based on assets under management; take the Vanguard Balanced Index Fund (ticker: VBIAX) as a back-of-the-envelope proxy for a typical 60% equity/40% bond portfolio. Those managed assets—and the firm’s revenue—have fallen by some 20% year to date (assuming no acquisition of clients or firms).

Firms more prudent in their borrowing, yet focused on growth, are in a good position.

“I think for people like Creative Planning or even Captrust, which historically have not carried a lot of leverage and have businesses generating really strong cash flows, I think you’re going to see them kind of dominate the headlines in terms of acquisition,” said a source close to the RIA deal-making community who declined to be named.

Firms with more leverage on their books are going to be under pressure. He said some operators were modeling financing costs at 5%; now pricing hovers around the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR) plus 600 basis points, or over 9%, nearly double the previous assumptions.

“For some of these private companies, before the market took a dip, they were carrying six times leverage,” this source said. “And now they might be carrying 7 1/2 or eight.”

Amit Dogra, president and chief operating officer at tru Independence, a platform for RIAs, said that he is starting to see a change in the makeup of buyers, many of whom are becoming much more discerning. While there’s an increase in the number of firms coming to market, the large, serial aggregators and consolidators are staying away from what they see as lower-quality prospects.

That paves the way for more emerging buyers to enter the space and try to get a foothold. He expects to see more of an infusion from private equity looking to scoop up bargains, squeeze the firms and exit on a traditional timetable.

“Private equity doesn’t view it the same way as (the aggregators) do,” Dogra said. “Where the risks will come in is for larger RIAs who have gobbled up advisors, they’re the ones who will slow down because it won’t make sense to them because they’re not looking to sell it. Private equity has an exit strategy built into it. Advisors don’t. These larger advisors don’t. So, it’s going to change the makeup of the type of buyer.”

Yet some aggregators or large acquirers who have made that deal with private equity already may be on a treadmill they can’t get off, he said.

“You’re not being an acquirer, because you don’t think the deals are good, but now you also have the pressure of this leverage, and the markets are down and interest rates are up. And is (this debt) callable?” he said. “Are you going to have to make decisions differently than you did before? Whether that’s cost cutting, whether that’s staff reduction.”

Or maybe some firms decide to double down on deals, Dogra said, to pay down their debt.

“So robbing Peter to pay Paul—moving one bucket to the other.”

Valuations and Deal Structures

Valuations for RIA firms have reached all-time highs recently. But Larry Roth, former CEO of Advisor Group and Cetera Financial and founder and managing partner of RLR Strategic Partners, said he’s starting to see those multiples crack. Last year several firms traded at 20 times earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization (EBITDA); now he’s seeing numbers around 16 times EBITDA, or 18 at the high end, he said.

“There is likely to be a period—I don’t know how long that is—of transition from lofty valuations and what people were hoping to sell at one point when money was basically free, to ‘Is there a price where the market clears,’” said Bradley Kellum, partner in the Americas Wealth and Asset Management practice at global management consulting firm Oliver Wyman. “In other markets, that tends to slow activity.”

Roth said he’s also seeing some change in deal structures. Previously, sellers would sell 90% to 100% of the business. Today, some might sell 60% now and the balance at the end of three years, on the optimistic assumption that the market will bounce back. The hope is that they’ll get the full value on the second piece of the business.

A Case of Indigestion

Another point of pressure is the ability of these firms to bring on more RIAs, integrate them into the business and find synergies.

Kellum said it requires more bandwidth, time and money to train and onboard acquired advisors as these firms become larger enterprises with more national footprints.

“As you see acquiring firms want to scale these platforms—like wanting to bring more advisors or more firms onto the platform—I either do more deals of the same number of advisors, or I have to go after bigger targets,” Kellum said. “Either one creates more onboarding complexity.”

tru Independence’s Dogra said some firms are struggling to integrate what they already have.

“You’ve heard firms say, ‘Oh, we’re going to digest what we have, or ‘We’re going to focus on what we have,’” Dogra said. “Those are called consumption pains, where ‘We have not aligned or integrated or found cost savings in what we have, and now we need to focus on that. Or we’re not delivering from a service, organic or value proposition perspective.’”

Tibergien said many of the buyers are still just financial buyers, and if they don’t integrate, then they don’t have a platform. If they don’t have a platform, he argues, they can’t move into the expansion and growth phase.

“This becomes a challenge for consolidators, whether or not they want to be a portfolio manager holding a bunch of advisory firms as their asset on which they get a return, or whether or not they want to build a truly consolidated business that allows them to grow,” he said.

The ‘Bear Stearns Moment’

RIA M&A experts don’t expect to see a wave of defaults and failures among the consolidators. More likely, deal-making moves upstream.

The evolution from fragmentation to consolidation has happened in almost every industry, Tibergien said.

If you look at the top 2,000 RIAs that have over $1 billion in assets, roughly 30% are corporate owned at this point, he said.The RIA industry is further along the consolidation curve than 10 years ago, but with plenty of room for more in the years ahead.

At this point, the big players are feeling the heat, faced with increasing costs of business, higher operational risks and declining markets putting pressure on future earnings, Tibergien said. That probably means we’ll soon see more consolidation among the consolidators.

“You won’t see a failure, but I think you will see almost a ‘Bear Stearns moment.’ Maybe it’ll look a little more dignified. But you’ll see some of these guys strategically merge because they’ve got to cut expenses due to debt funding costs doubling,” said the unnamed source close to deal-makers.

“I think you’re going to see some of these overleveraged guys look at exits. They’re not just going to throw up the white flag and say the lender’s going to have the business.”