The push to broaden fiduciary protection for investors at the federal level is looking more and more like a lost cause, so states are starting to step into the void. And that’s prompting some disagreements among organizations that represent financial planners.

The Department of Labor fiduciary standard is dead, and the Securities and Exchange Commission is moving toward adoption of the so-called Regulation Best Interest standard, which is likely to cause even greater confusion about the roles and fiduciary responsibilities of broker/dealers and advisors.

The federal retreat has prompted some states to enact fiduciary rules of their own. Nevada lawmakers approved a law last July that extends an existing fiduciary law to include not only financial planners but stockbrokers and other commission-based investment representatives. Advisors also must disclose profits or commissions they earn on client investments.

Legislation also has been adopted in Connecticut; New York, New Jersey and Maryland also are considering fiduciary legislation. “Given the inadequacies of the SEC proposal, a number of states will be considering the options they may have to strengthen protections for investors,” says Barbara Roper, director of investor protection at the Consumer Federation of America.

Groups representing b/ds and the insurance industry have made clear that they will fight any state-level initiatives. SIFMA and other trade groups have argued that the National Securities Markets Improvement Act of 1996 limits the ability of states to create new recordkeeping obligations for b/ds and may contain other barriers to state action on fiduciary standards.

Roper agrees that any state rules will need to be crafted carefully to avoid violating the NSMAI. “I think it is possible, but any state that goes that route will have to be prepared to face intense industry push-back.”

Meanwhile, an interesting difference of opinion has surfaced between key organizations representing the planning profession. The Certified Financial Planner Board of Standards announced in September that it would oppose regulation of financial planning as a distinct profession by states, citing the cost and regulatory burdens for planners who work in multiple states.

Meanwhile, the Financial Planning Association has staked out a somewhat different position. In a statement to its members, FPA said: “In this increasingly competitive landscape, we don’t believe it serves our members’ or the profession’s interest to dismiss any national or state advocacy strategy. Frankly, what seems right today from a policy or strategy standpoint, may not be right tomorrow.”

Frank Paré, a CFP and FPA’s president this year, explained to me in an interview that they’re really is not a huge amount of daylight between his organization and other key organizations.

“We all agree that a federal solution is preferable,” he said. “Where we differ is that FPA doesn’t think that actively opposing any state regulation, or not showing up to press our view of what a state regulation should look like, is a solution.”

Richard Salmen, a CFP and the CFP board’s chairman, took a similar line in a press briefing held during FPA’s recent annual conference. “The word “split” is too strong,” he said. “FPA is a membership group—it needs to be responsive to its members. Our responsibility is certifying. And we don’t believe state regulation is the most effective way to elevate the profession.”

Paré stressed FPA’s membership mission as well. “We should not stay silent, because we have members in these states who want someone to advocate on their behalf,” he added. “If a rule is working its way through a state legislature and our members will be impacted by that law passing, then we have to do something, right?”

In some cases, FPA will oppose regulations, he said. “Or, it could involve showing up and indicating where there may be some problems and to suggest improvements.”

FPA’s key goal, he said, is consistency—that is, regulation with uniformity across state lines. “At the end of the day, we all want consistency on fiduciary standards, whether state by state or ideally at the federal level. But federal action doesn’t seem to be coming anytime soon, so absent that we have a decision to make—how do we advocate on behalf of our members?”

Is consistency among states a practical objective, I asked?

“I don’t think so,” he replied. “But we still want to approach each state with consistent language that we hope will be used.”

FPA is working on model language that will be based on the CFP board’s recently updated Code of Ethics and Standards of Conduct.

There is plenty of reason to worry about developments on the federal level. As proposed, the Regulation Best Interest contains poorly defined standards and confusing consumer disclosure forms. “We think it will cause greater confusion,” says Paré. “You have a regulation on best interest that doesn’t even define what best interest is, and it doesn’t include a fiduciary duty of loyalty.”

And usability testing conducted earlier this year of the proposed SEC Customer Relationship Summary form brought up numerous serious problems. The tests of the form—a central component of the proposed rules—were conducted by AARP, the CFA and the Financial Planning Coalition.

The tests showed that investors:

- Did not understand the form’s legal disclosures or the term “fiduciary standard.”

- Based on their understanding of the term “best interest,” viewed the CRS as portraying brokerage accounts in a more favorable light than advisory accounts.

- Did not understand critical distinctions between different payment models, fees and associated services.

- Could not figure out which type of fees might cost more.

- Thought conflicts would not impact them.

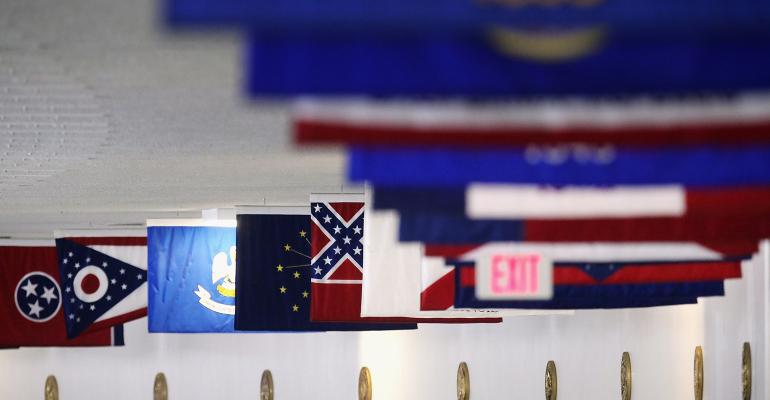

The bottom line: Confusion about fiduciary roles likely will be rampant in the marketplace in the foreseeable future as the federal role diminishes. A strong federal standard would be best; a checkerboard map of state regulations will only create some difficulties for planners, but some protection will be better than none.

In this respect, the debate over federal and state responsibilities is beginning to resemble the ongoing fight about a retirement savings policy.

The Obama administration proposed addressing the problem of workers not covered by employer retirement plans with a national auto-IRA program. Workers would be enrolled automatically in Roth IRAs tied to payroll deduction systems. When Republicans blocked that effort, states began launching auto-IRA programs of their own.

Oregon was the first out the gate with a plan and other states, including California, Illinois and Maryland, are getting ready to launch their own plans. Again, federal policy would be better, but lacking that, states are stepping up.

If current trends in Washington continue, we can expect more—not less—of this regulatory fragmentation in the years ahead.