Penny Pennington, the new managing partner of Edward Jones and the first woman to lead the nation’s largest brokerage firm (by headcount), wakes up at 5:15 a.m. every morning and meditates, kneeling in either the library of her home or an outdoor garden for a moment of calm. It’s a daily ritual done in silence–she doesn’t use meditation apps or play music.

She practices intermittent fasting and skips breakfast but makes sure to drink 40 ounces of water during her brief 10-minute drive to the office. She takes the same route every day, she says.

A focus on ritual, routine and process, while still being open to new ideas, could describe Pennington’s approach to Edward Jones as well. The 97-year-old firm’s granular focus on selling investments to middle-class clients has helped it grow to $1.1 trillion in assets and become a seemingly ubiquitous presence in neighborhoods all across the country, with more than 14,000 immediately identifiable offices in stand-alone houses, strip malls and main streets across the country.

But it is also an easy target for critics, who see an old-fashioned, largely commission-based brokerage where recruits, like religious missionaries, go door to door to drum up new business. It’s seen by many as a cold-calling shop, an anachronism in a world of registered investment advisors, fiduciary mandates and financial planning.

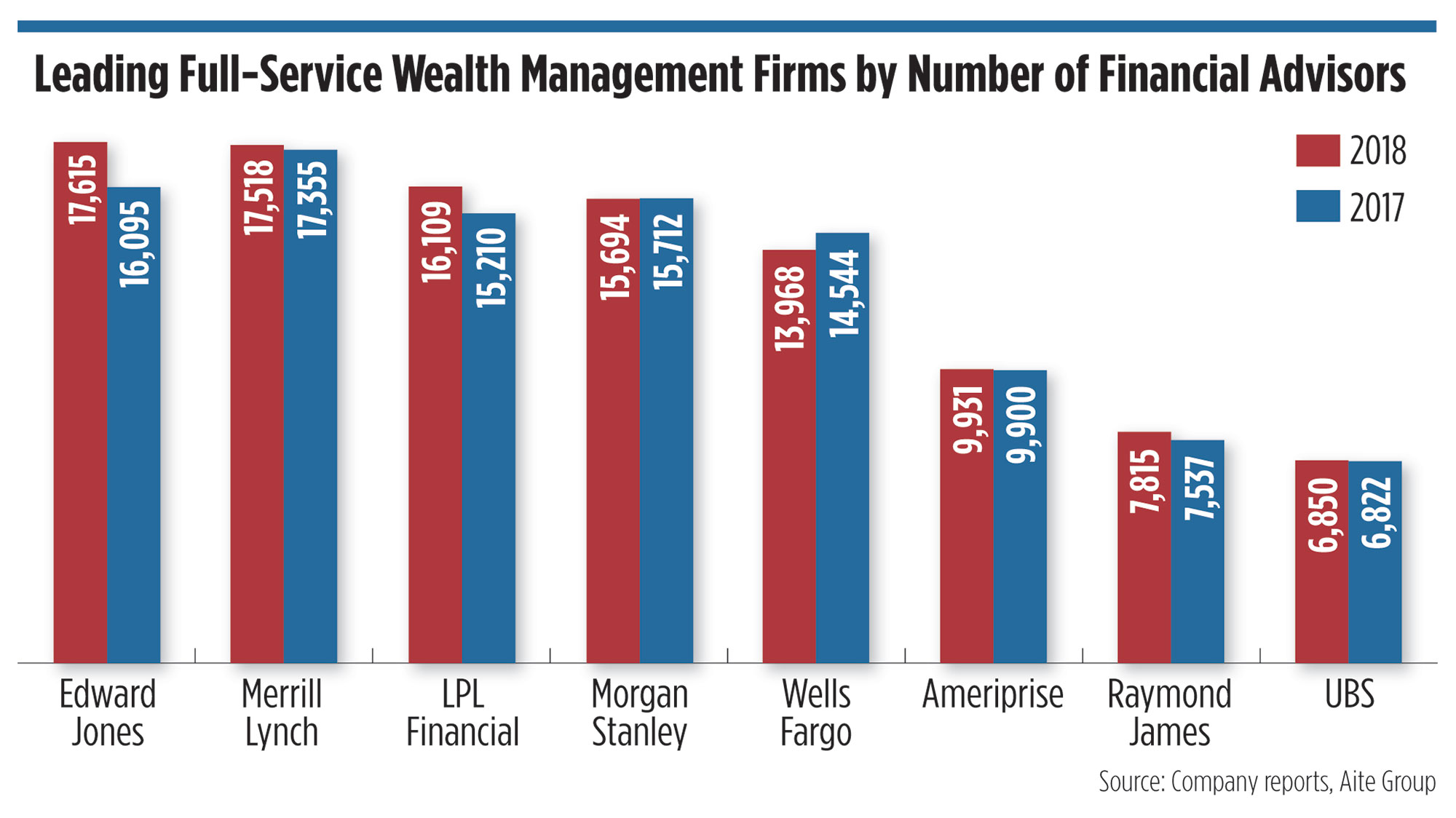

And yet in many ways Edward Jones is steps ahead. While other firms talk a lot about the need for a more diverse workforce, Edward Jones has moved the needle. Employees there are younger than the industry average, with greater racial and gender diversity. It’s consistently ranked as one of the nation’s best places to work, with broker satisfaction levels far outpacing other firms. And, unlike many of those other firms, it’s growing. The firm added over 1,000 advisors in the past year, part of a stated goal to grow to 20,000 by the end of 2020, and eventually 30,000.

“It’s a very structured, franchise-like business,” said Dennis Gallant, a senior analyst for Aite Group’s Wealth Management practice. “Despite what everyone wants to say about them, it works.”

Pennington says she realizes the firm’s structured approach is important to achieve its aggressive growth goals, but so is a willingness to adapt to the times. Small changes are already underway, starting with the managing partner’s office.

A wall and large wooden doors were replaced with glass. Decades-old dark paneling and bookshelves were torn out. The office is now filled with contemporary furniture in gray and purple hues.

Adjacent to her L-shaped standing desk, amid a bust of the founder’s son Ted Jones and photos of the previous managing partners is a replica of the “Fearless Girl” statue. When Pennington learned the artist behind the statue was selling replicas and donating the proceeds to charity, she had to have one, she said.

“[Our history] gives us perspective on the way we lead the firm. It doesn't tell us what to do, and it’s not so precious in that we never do anything that leads us into a more contemporary way of serving our clients,” Pennington told Wealthmanagement.com during a tour of the office.

Before leaving Comerica Bank 20 years ago to join the brokerage, Pennington said she was a “middling” professional. At Edward Jones, she found the partnership structure supported a unique communal effort by employees to grow and better the firm, and each other. Pennington said her mentors at Edward Jones taught her leadership and collaboration.

“The organization has poured into me, has inspired me, has given me things that I had no idea were possible in my professional or personal life,” Pennington said. “I want to give back to it. I want to help make it an even better place.”

One thing that won’t change: Advisors at Edward Jones don’t turn away investors. Their model means they can do business with anyone, even if that means only a handful of transactions for, say, retirement accounts an investor has collected working for different employers over the years.

Consequently, the percentage of fee-based assets at Edward Jones lags behind some other independent broker/dealers and the wirehouses. In 2018, Edward Jones had $334 billion in fee-based assets, representing about 30% of total client assets just above $1.1 trillion.

Although Edward Jones almost tripled its percentage of fee-based assets from 12% in 2011 to 30% in 2018, LPL Financial has gone from 32% of client assets in fee-based programs in 2011 to 62% in 2018. Fee-based assets at Merrill Lynch and Morgan Stanley reached 47% and 45%, respectively. UBS and Wells Fargo haven’t shifted assets into advisory accounts at the same pace. Only 36% of assets are in fee-based accounts at UBS and 34% are at Wells Fargo.

The persistence of commission-based business currently has Edward Jones in a standoff with the CFP Board; it remains an open question whether Edward Jones advisors will be allowed to use the designation given the board’s higher fiduciary threshold for designees. A spokesperson for Edward Jones says the firm is discussing the situation with the CFP Board and no decisions have been made.

As you would expect with smaller clients, productivity per Edward Jones advisor was $446,928 in 2018, well below that of Morgan Stanley, Merrill Lynch and UBS advisors, whose productivity hovered around $1 million per person in 2017 and 2018, according to Aite Group.

But while wirehouse workforces have remained stagnant or shrunk, Edward Jones is on pace to achieve its goal of 20,000 by the end of next year. It added more than 1,500 advisors in 2018, a 9.4% increase, bringing the total to 17,615.

The next closest competitor was LPL Financial, which grew at about half that rate. As of May 24, Edward Jones had hired another 444 advisors so far this year, bringing its total to over 18,000, a spokesperson for the firm said.

If Edward Jones can keep adding 1,500 advisors each year, it will have more than 30,000 before 2027.

“It sounds extremely aggressive and cost intensive,” said Greg O’Gara, a senior research analyst for Aite Group’s Wealth Management practice. “I haven’t seen anyone move the needle by a thousand additions a year in a long time, if ever.”

Achieving that growth rate will mean relying on career-changers and recruiting experienced advisors to the brokerage, often in metropolitan centers, which the firm has not done historically.

Diversity

Edward Jones is also defying the impact an aging and shrinking industry workforce is having on some other firms. The average Edward Jones advisor is 45 years old, the company said. The industry average is 51, according to Cerulli Associates.

Women accounted for 20.1% of Edward Jones advisors in 2018, up from 18.9% in 2016. That’s slightly ahead of the industry average. Over 7% of Edward Jones advisors are minorities, up from 6.6% in 2016. Industry-wide statistics are hard to come by, but for reference, the CFP Board says only 3.5% of its 80,000 designation holders are black or Latino.

Earlier this year, Edward Jones began paying brokers 10% more for any assets they transition to women or minorities to hasten the diversification of its workforce.

Emily Pitts, a principal of Inclusion and Diversity at Edward Jones, said the goal is to better represent current and potential customers–people want to do business with others like them, she said.

“I also add a caveat that I think we have to be careful when we talk about attracting diverse talent,” Pitts said. “It does not have to be an African American financial advisor doing business with an African-American client. My clientele was probably 70% Caucasian because of where my office was located. But I do think, as an industry and as an organization, we have an opportunity to build our businesses cross culturally.”

Inspired by an initiative at PricewaterhouseCoopers, Pitts asked Pennington’s predecessor Jim Weddle in 2018 to sign a corporate pledge to promote dialogue about diversity between employees, which he did. Edward Jones then organized 40-person group discussions on unconscious bias and micro-inequities. More than 1,000 Edward Jones employees who work in St. Louis participated.

“The impetus for these conversations is first identify solutions, possible solutions, that are either at the grassroots level or at the firm level, as to what we can do to improve the culture, the inclusiveness, I should say, of the firm, attract more talent to the firm, better understand our clients opportunity, all of these things,” Pitts said.

Pennington signed the same pledge in January, and this year over 1,500 people signed up.

The firm is also in the process of a multiyear transformation of its client experience too, including the workflow of its branches and the digital tools used by advisors and clients, said Kevin Alm, the head of Solutions within Edward Jones’ Client Strategies Group. It’s improving the ability for Edward Jones to give clients better goals-based advice, because clients are asking for it, Alm said.

To standardize the process, the firm has established a linear three-step method of discovery, goal-setting and execution. Clients will have the choice of working through those steps in an Edward Jones office, at their home or online. Each contact with a client is a chance to revisit their risk tolerance, understand what their goals are and review their portfolio. All the recommendations that come out of the process should be agnostic to advisory or brokerage accounts, Alm said.

“So, if a client says to us: ‘Look, I don't want to make any of these investment decisions. I’m not interested in individual security selection. I don't want to do any of that,’ our advisory solutions mutual fund advisory platform is perfect, right? Others are the opposite; they want to be very engaged. They love individual security selection. Well, we’ve got two choices for them. We have a fee-based option, and we have the broker/dealer option,” Alm said. “We’ve maintained this position, principally because of what our clients need, but I think we also look at it from our business model and say, it’s just good diversification of our revenue.”

Whether the rapid growth that Pennington has planned for Edward Jones is sustainable without compromising the firm’s distinct culture, the quality of new advisor training or profitability, remains to be seen.

Alan Kindsvater, a principal at Edward Jones who leads advisor training, has worked at the brokerage for 32 years and isn’t fazed by adding more brokers. Training itself has changed dramatically since Kindsvater became the 1,065th advisor at the firm, but he’s seen the regional structure scale to 18,000.

“How are we going to reach 18,000 financial advisors? Well, we’re not going to do it by scaling up in the home office to deliver one-on-one attention to every branch team,” Kindsvater said in May. “We’re going to do that for our new financial advisors, we’re going to do that for our most productive, and we’re going to reach everyone else through this network of volunteers in the regions and skill them on what that looks like, starting with the business plan.”

At other brokerages, financial incentives to become a branch manager or lead firm initiatives make for worse candidates in those roles, Kindsvater said. Advisors at Edward Jones volunteer to take on other responsibilities, he said, part of the familial culture of the firm, which starts at the top.

Pennington describes herself as the lid of Edward Jones, which “can only go as fast as I’m willing to grow and develop and contribute,” she said.

“I am, every day, growing in ways that I knew to expect because I’ve been here at Edward Jones for 20 years. But now in this role people would say, ‘Wow, you’ve arrived,’” Pennington said. “That’s not the way I feel at all. The way it feels is I’ve got so much more growing and learning to do. It makes me a little positively anxious every day.”

(Ed note; this article has been updated to correct an error; Edward Jones pays brokers a 10% incentive to turn any or part of thier books over to a minority or female advisor. The original story said they only paid the incentive to retiring brokers.)