(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The housing market is in tough spot, with 30-year mortgage rates averaging more than 7%, housing starts and prices falling, and those in the know predicting worse times ahead. So why were more than 1.7 million housing units under construction in the US in September, a new all-time high?

Part of the answer is that the housing market is in a tough spot, and builders are slowing the pace of construction because there’s not much point in rushing. But as should be apparent from the above chart, it’s construction of apartments, not single-family houses, that is breaking records and, well, apartments are different.

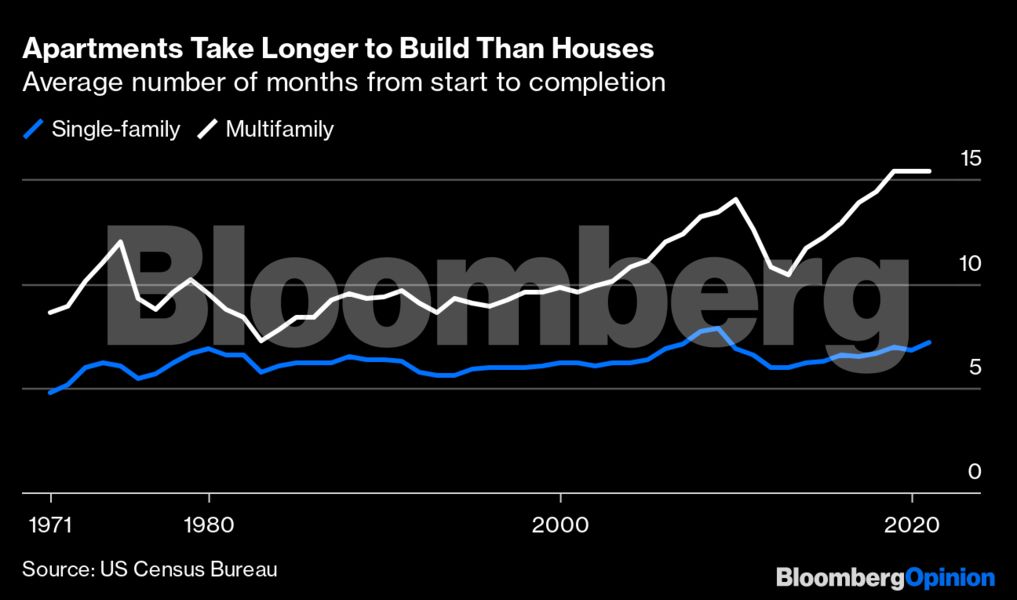

One way in which apartments are different is that it has always taken longer to build them than single-family houses, and the gap has grown a lot lately.

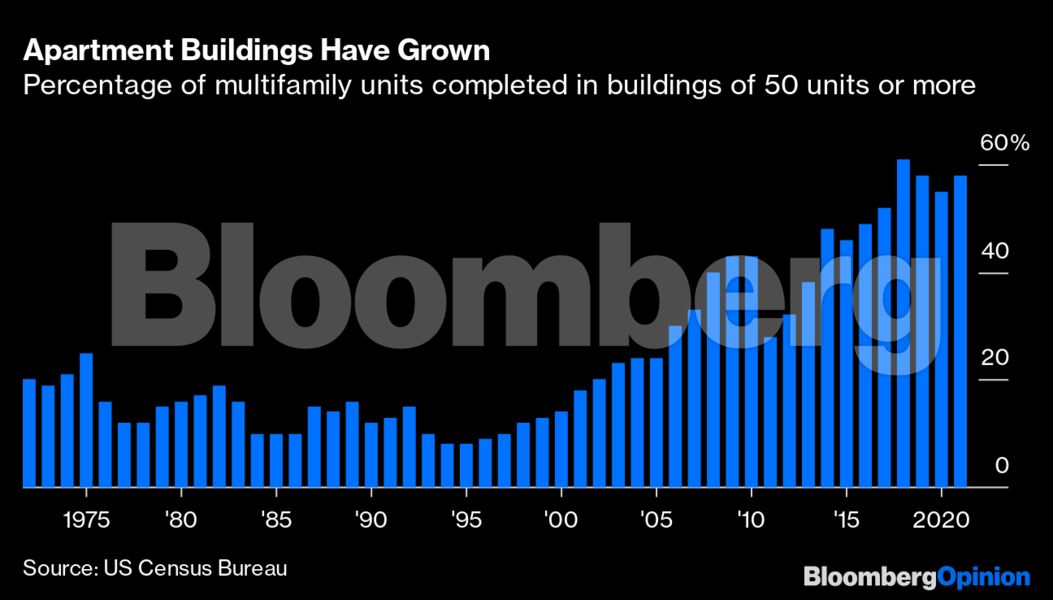

The big increase in multifamily time-to-completion over the past couple of decades is not so much because builders have become slower but because the buildings have become much larger — and bigger buildings usually take longer to construct. Every year since 2017, most multifamily units completed in the US have been in buildings of 50 units or more, which had never happened before then (and yes, these statistics go back only to 1972, but I’m reasonably confident that this is a historical first).

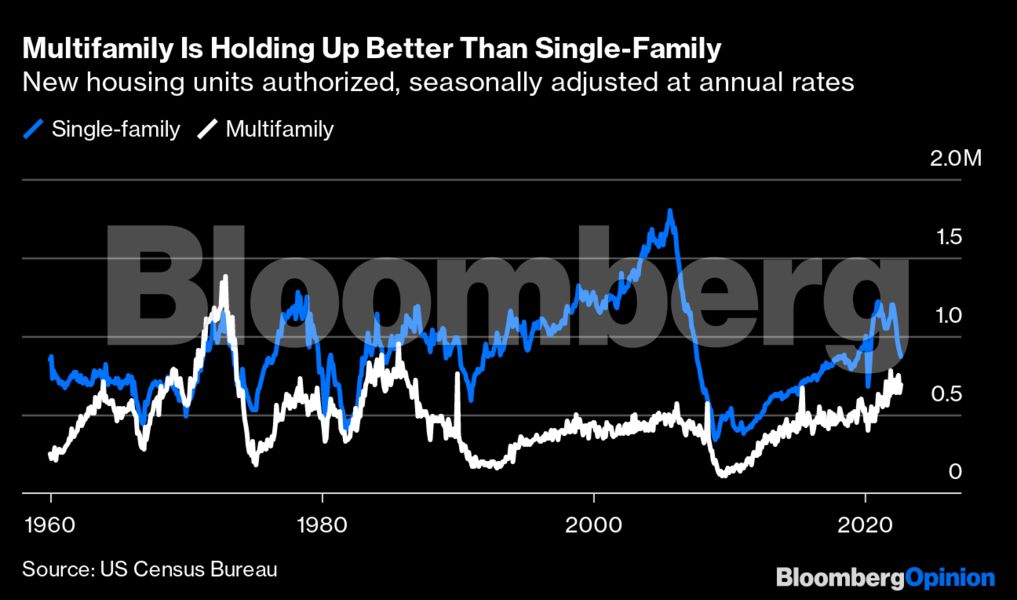

Bigger buildings and longer construction times go a long way in explaining why apartments have made up the majority of housing under construction for the past few years, something that hadn’t happened on a sustained basis since the early 1970s, but they don’t explain everything. Housing-permit statistics, which aren’t affected by construction time, show (1) more multifamily housing being permitted than at any time since the mid-1980s and (2) barely any decline in multifamily permits in recent months, a big contrast to what’s been taking place in single-family construction.

Multifamily investors rely on a different set of financing tools than individuals who are buying single-family homes, so they don’t seem to have been as affected by interest-rate increases — yet. The capitalization rate for prime class A multifamily assets, a measure that kinda-sorta represents the interest rate on new multifamily investments, was still below pre-pandemic levels at 4.09% in the third quarter, according to CBRE Research.

Still, it is interesting that developers are continuing to put up so many big apartment buildings despite a pandemic and remote-work boom that many assumed would spur a shift away from apartment living. CBRE Research also reports that multifamily investors are now more optimistic about future rent increases in so-called gateway markets — the biggest, most expensive metropolitan areas — than in smaller ones. Maybe these investors know something about the future that the rest of us are missing.

Or maybe they don’t: The multifamily building booms of the mid-1980s and early 1970s both ended unexpectedly, after all. The 1970s boom seems to have been driven by millions of baby boomers entering adulthood, along with billions of dollars in federal public housing subsidies and the rise of the then-exotic form of homeownership called the condominium. It ended abruptly when the 1973 oil crisis sent inflation, interest rates and unemployment skyrocketing. The 1980s boom was clearly driven in part by tax incentives, given that it withered when they were removed by the 1986 tax reform.

Something will eventually halt the current multifamily boom, too. But the crash isn’t happening yet.

More From Bloomberg Opinion:

- Downtown San Francisco Can’t Shake Working From Home: Justin Fox

- Downsizing? Rising Interest Rates Are Your Friend: Conor Sen

- Buying a House Now Wouldn’t Be a Bad Idea: Teresa Ghilarducci

© 2022 Bloomberg L.P.