The emotional turmoil that cooler heads simply call “volatility” surely sends a spasm of fear down the spines of those in, or on the cusp of, retirement.

After all, we’ve been through this in 2000 and again in 2008, which don’t feel so long ago, and those memories have resurfaced vividly. The difference today, however, is demographics. At that time, baby boomers and older Gen Xers had a long runway to retirement. As painful as the bear markets were, they had time to make up for losses. That’s no longer the case: a bear market in equities now damage, perhaps devastate, the plans of millions of people looking at retirement.

One of the factors that’s hurting stocks surely is the rise in interest rates across the yield curve. The front end is hit by the Fed’s tightening while the longer end faces fears of inflation and the rapidly rising federal budget deficit forcing more Treasury debt into the market. However, there are ample reasons to expect the rise in yields to be limited, and its peak not too far away. In short, it may very soon be time to look at the bond market with fondness.

The rise in the federal budget deficit is ample reason to expect yields to rise. The Congressional Budget Office just updated its forecasts and puts the deficit at $981 billion in 2019, from $689 billion, and sees a $1 trillion deficit in 2020, two years sooner than in their prior estimates. Blame the recent tax plan for that. Simple supply and demand math tells you more supply warrants lower prices—which in the case of bonds means higher yields, right?

Not so fast. The flipside of the budget coin will be a major deficit and more Treasury issuance to the bond market. It’s already started, but that’s only been the tip of the iceberg. The thing is, all those bonds will actually force buying and that forced buying will inhibit a dramatic rise in bond yields.

It works like this: Fixed income portfolio managers and ETFs follow various bond indexes. The broadest, and largest, contains U.S. Treasurys. As more Treasurys come into the market, those same Treasurys enter a given index and investors have to buy those to keep pace with the changes. It’s identical to a stock entering the S&P 500: when it’s added, benchmarked or indexed funds have to buy that particular stock, sending its price up. Bond indexes are no different.

One of the largest bond ETFs is the iShares Core U.S. Aggregate Bond (AGG), which tracks an index composed of the entire U.S. investment-grade bond market and has about $55 billion in assets under management. U.S. Treasurys make up 37.8 percent of that ETF. It’s a given that as the deficit soars, increased issuance will lift that 37.8 percent weighting sharply.

An added quirk is that the Fed is reducing the size of its balance sheet by buying fewer Treasurys. When the Fed, in its various bouts of quantitative easing, bought Treasurys that were concentrated in longer maturities, they were taken out of the index. Now they too will enter the market—and hence the indexes. In other words, as the federal budget deficit drives more and more Treasury bond issuance, indexes will gain a proportionally larger share of Treasurys and investors will be forced to buy.

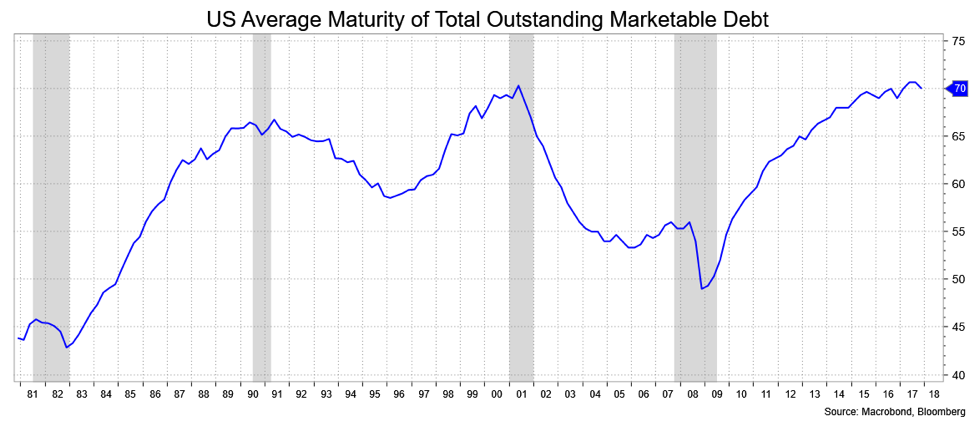

Not only will they be forced to buy, but what they buy likely will be longer maturities. First, over the course of the recovery the average maturity of outstanding Treasury debt has increased dramatically—to a near record 70 months, from less than 50 months in 2008. In short, as the Treasury market has gotten longer so too has the Treasury allocation in an index. Expect even more of an increase.

The Treasury Department has said otherwise: it doesn’t want the average maturity to increase, but I think they’re wrong. First, if rates remain historically low, it makes sense to add longer-term debt. Second, if the Fed continues to hike rates in the intermediate term and the yield curve flattens, that’s an incentive to issue more at the long end. Third, many countries have issued longer-term debt—40-, 50- even 100-year maturities. There clearly is demand out there; in the event, the average maturity would rise even more.

David Ader is Chief Macro Strategist for Informa Financial Intelligence.