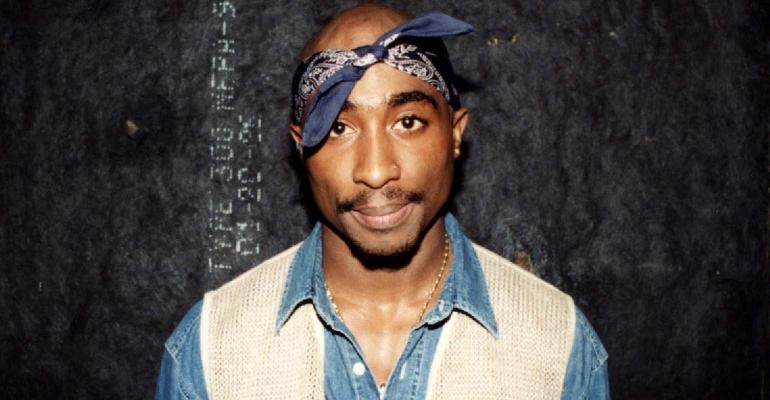

West coast rapper Tupac Shakur was tragically murdered in 1996, but his estate continues to be at the center of legal woes. His late mother, Afeni Shakur-Davis, who was Tupac's sole beneficiary, spent years battling over rights to royalties and master copies of his unreleased songs. More recently, earlier this year, Shakur’s sister, Sekyiwa Shakur, along with the Tupac Shakur Foundation, sued the executor of Shakur’s estate, Tom Whalley, alleging he has embezzled $5.5 million.

Whalley has been the executor of the estate since Afeni’s death in 2016 and in charge of managing Amaru Entertainment, a record label founded by Afeni that’s responsible for Shakur’s classic LPs and posthumous albums, among other things. According to Rolling Stone, Whalley is accused of unreasonably enriching himself at the expense of the beneficiaries by taking excessive compensation. He’s also accused of withholding tangible personal property, left to Sekyiwa, for “investment purposes.” In his defense, Whalley argues that the trust granted him “absolute discretion” to withhold and use the items to make money for the estate.

In a follow up to that claim, last month, Sekyiwa asked the court for an independent estate audit, arguing that the accounting provided by Whalley “falls woefully short of compliance with the legal and accounting requirements of the trust.”

Who Owns the Right to the NFT?

The estate’s latest legal dispute over who owns the rights to the cover art for Shakur’s last album, The Don Killuminati: The 7 Day Theory, which was posthumously released two months after his death in 1996. The art, designed by Compton, California artist Ronald “Riskie” Brent, controversially depicts the late rapper as Jesus Christ nailed to a cross, which he eerily approved prior to his death. Ownership rights to the art came into question after it was announced in May 2022 that the art will be turned into a non-fungible token (NFT) to be sold at auction by Heritage Auctions in Dallas.

Though the details are somewhat murky, according to TMZ, Brent sold the painting he designed back in 2015, but crypto and NFT wallet Manager Zelus helped him recover the art (this is supported by court documents filed by the two parties showing that the art was sold and later purchased by Zelus in 2021 for an undisclosed sum). Meanwhile, Sekyiwa sent a letter to Heritage Auctions asserting that the art falls under “the umbrella of the late rapper’s property” and that as successor-in-interest, she “owns all of Tupac’s DRR releases and recordings, including…all of the artwork created in connection with those releases and recordings.”

In response to Brent’s and Zelus’ claim of ownership rights, Shakur’s estate filed their own legal claim to the work. As reported by Quartz, the June 15 filing states, “The painting was created by a DRR employee (Brent) in the regular course of his job duties at DRR” and invokes the work-for-hire doctrine under the U.S. Copyright Act. Under the work-for-hire doctrine, if the work is made for hire, the employer or other person for whom the work was prepared is the initial owner of the copyright unless both parties involved have signed a written agreement to the contrary.

The Heritage Auctions website nonetheless states that the art piece, along with its associated NFT, was sold to a winning bidder on June 18, 2022 for $212,500.

Is There a Copyright Issue?

According to Jonathan Steinsapir, a partner at Kinsella Weitzman Iser Kump Holley in Los Angeles, “There doesn’t appear to be a copyright issue in this case, but rather a question of who owns the property—the physical artwork—so the work for hire doctrine is only marginally relevant, if at all.” He further explains that as owner(s) of the painting, Brent and Zelus have the right to sell the painting—however, the issue may be that Brent improperly acquired the painting in the first place. If it’s found that the record company who hired Brent to create the painting never stipulated that the original was his to keep, than the estate may be able to prevail on its argument that the painting belongs to it.

The NFT part gets a bit more complicated. In general, selling an NFT with an image of the album cover art doesn’t mean that the buyer of the NFT acquires any copyright to the original image. Copyright law doesn’t give an NFT owner any rights unless the creator takes affirmative steps to make sure that it does—for example by executing a copyright licensing agreement to the work connected to the NFT.

It’s not clear what, if any, rights the estate is claiming to the 1/1 NFT that was auctioned off together with the physical painting. If the NFT is an exact copy of the album cover art, a court may find that the creator infringed on the estate’s copyright to the exclusive use of that intellectual property.

A relatively new sector of assets, NFTs are inevitably ripe for legal disputes, including copyright issues and beyond; this case is likely just the tip of the iceberg as NFTs, bitcoin and the like continue to gain popularity.