By Nir Kaissar

(Bloomberg Gadfly) --Conflicts of interest won’t make brokers any richer. Not anymore.

If you’re in the business of recommending mutual funds to investors, you probably shouldn’t also take money from the funds you recommend. And if you do, you should probably disclose that to your clients, right?

That, in a nutshell, is the principle behind the Department of Labor’s fiduciary rule, issued last April over the moaning and wailing of brokerage firms and scheduled to take effect in two months. Critics of the rule are attempting to delay its effective date in the hope that President Donald Trump will revoke it in his anti-regulatory fervor.

Critics of the fiduciary rule aren’t defending the conflicts that the rule brings to light. Instead, they complain that the rule is too burdensome. Tim Pawlenty, CEO of the Financial Services Roundtable, grumbled that “the current rule is overly complex, involves too much red tape and is already negatively impacting consumer choice and service.”

That objection is a red herring, however. For one thing, if critics were worried about the rule’s burdens, they would argue for a more narrowly tailored one rather than its elimination. Also, many of the rule’s burdens relate to exceptions that allow brokers to receive fees from mutual funds they recommend to clients if accompanied by appropriate disclosure. Brokers could avoid many of those burdens by simply declining fees from fund companies.

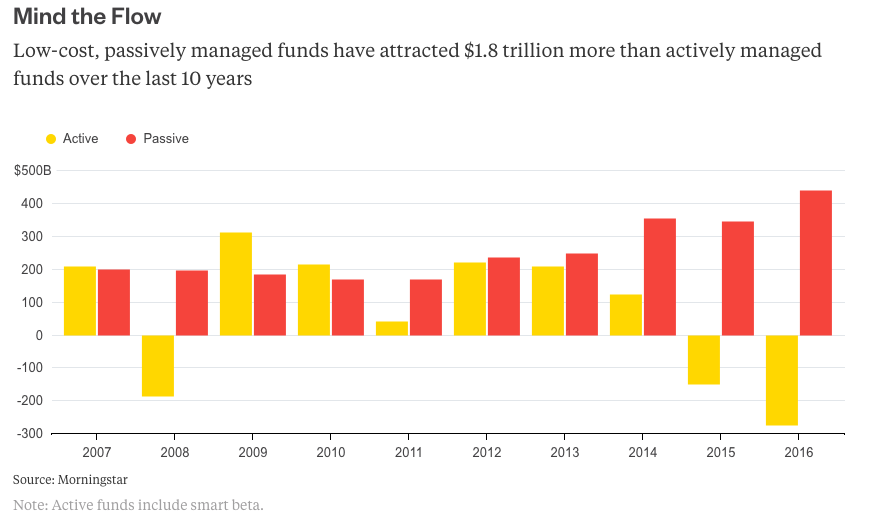

The real objection is that brokers’ wallets are shrinking. But brokers are fixed on the wrong culprit. Yes, the fiduciary rule makes it harder for brokers to collect fees from fund companies. The biggest threat to brokers, however, is that investors increasingly want low-cost, conflict-free investment options. Just look at the billions of dollars flowing into index funds and robo-advisers.

There’s nothing that President Trump or anyone else can do about that, and some brokers are getting hip to the trend. As a result, investors now have more choices than ever. Merrill Lynch -- the archetypal traditional broker -- now offers discount brokerage accounts and low-cost robo-investing. And a growing roster of firms are rolling out robo-advisers of their own, including UBS, Fidelity and TD Ameritrade.

Rather than fight a misguided battle with the fiduciary rule, brokerage firms should do more to clean up their conflicts. But old habits die hard. Morgan Stanley recently announced that its clients would only have access to ETFs that pay the firm a distribution fee. Morgan Stanley says that conflicts would be mitigated because 1) its financial professionals don’t receive compensation directly from the ETFs and 2) the fees are fixed, so there’s no incentive to favor one ETF over another.

That may be true, but it doesn’t address the root conflict. Morgan Stanley’s clients no doubt believe that the firm recommends investment products that are in their best interests. In reality, however, Morgan Stanley will only recommend ETFs that pay it fees, which may not be the best choice for clients. That’s precisely the kind of conflicted advice that investors resent.

These pay-for-access arrangements are customary for mutual funds. Many brokers have curated lists of no-transaction-fee funds. They may look like the best investment options, but in reality they’re just funds that pay the broker a hefty distribution fee -- often as much as 0.4 percent annually.

That fee is passed on to investors in the form of higher expense ratios. The result is that no-transaction-fee funds are often more expensive than comparable commission-based funds. Brokers aren’t quick to point that out to investors.

I’m not suggesting that brokerage firms settle for lower fees. But if brokers want more revenue, they should compete openly and fairly in the market by taking their case for higher fees directly to investors. They shouldn’t enter into conflicted, backdoor arrangements with fund companies that pass on those higher fees to investors without their knowledge.

The fiduciary rule pulled back the curtain on one type of conflict, but there are many others. It’s only a matter of time before they come to light, too. Brokerage firms would be wise to end those conflicts before investors discover them and take their money elsewhere.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Nir Kaissar is a Bloomberg Gadfly columnist covering the markets. He is the founder of Unison Advisors, an asset management firm. He has worked as a lawyer at Sullivan & Cromwell and a consultant at Ernst & Young.

To contact the author of this story: Nir Kaissar in Washington at [email protected] To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at [email protected]