Any discussion of a potential impending recession should begin with borrowing.

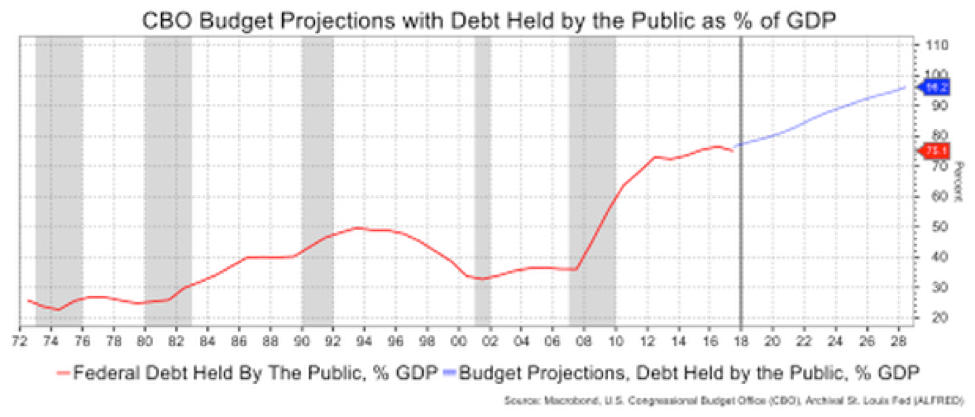

This (un)happy chart shows the total Federal Debt, held by the public, as a percentage of GDP:

Note where the vertical line is now as the debt percent grows forever. If and when we hit a recession, this deficit will grow even more. Why is this a problem?

- It means that government borrowing will crowd out the more productive and economically boosting borrowing from businesses and individuals,

- The fact the deficit has grown when the economy is strong is an anomaly. We should be reducing borrowing as a percent of income/GDP when things are good.

- If we have high debt in growth, we have less room to borrow when things are bad, i.e., government spending (or lower taxes) to boost the economy during a recession.

- More and more government spending will be on interest payments on the debt, aka debt service, which means less for other purposes.

- When the deficit gets larger, there’s the real risk of higher interest rates demanded by investors because the U.S. becomes a riskier credit.

- Taxes will have to go up to pay for the deficit and/or spending decrease, which gets back to Social Security and Medicare for retirees.

And that’s just scratching the surface.

Then there’s the consumer. We all know that while unemployment is low, wage gains have been pitiful for most people. This explains the doofus populism of Trump’s economic policies that ultimately will make things worse (e.g., see deficit above). But here’s the thing; we are a materialistic, short-sighted, stupid people who are envious of things. So when we don’t earn enough to support buying habits—tattoos on, tattoos off—we borrow, it means less for difficult times, the proverbial nest egg and, of course, retirement.

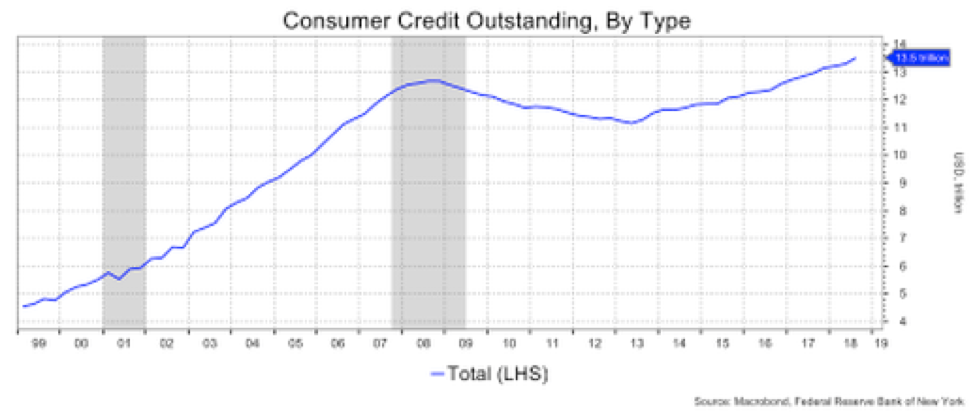

Don’t believe me? This next chart shows Consumer Credit, i.e., what we borrow, at $13.5 trillion. That’s $1.4 trillion more than just before the last recession—which was caused by too much borrowing. But here we are in a growth phase when, in theory, we should be relying on incomes to consume, not borrowing. With interest rates now higher, evidence is there, in softer auto sales and housing, that they’re taking a bite. People will borrow to maintain lifestyles, but watch out when they lose their jobs in a recession.

U.S. corporations have borrowed hugely. Why? Mostly to buy other companies and buy back their own stock. U.S. corporations have been the largest buyer of the stock market, in case you didn’t know that. It, maybe, made sense when rates were low and corporate borrowing rates (known as credit spreads) were very tight to U.S. Treasury rates. Well, the Fed is tightening, rates are up and people are pondering all the corporate debt out there.

Corporate debt is 46.4 percent of GDP, a record high. It traditionally gets over 40 percent in a recession, not in a growth phase, which means when a recession hits, the quality of corporate debt—the credit rating—will get worse in the form of downgrades.

If fears of corporate indebtedness are strong (they are), then there’s less room for borrowing to buy back stocks, which means we lose the biggest buyer of the stock market in the last 20 years. That’s not good for stocks, is it? Oh, and the fact they’ve used debt to buy back stocks means they’ve haven’t been investing in organic growth that boosts productivity and real profits.

A related issue is that the investment-grade corporate bond market is of lesser quality now than it was. There’s been a lot of triple B issuance, so the overall credit rating of the corporate market is weaker. In a recession, credit spreads will widen more than tradition, making it more difficult for corporations to borrow and expand.

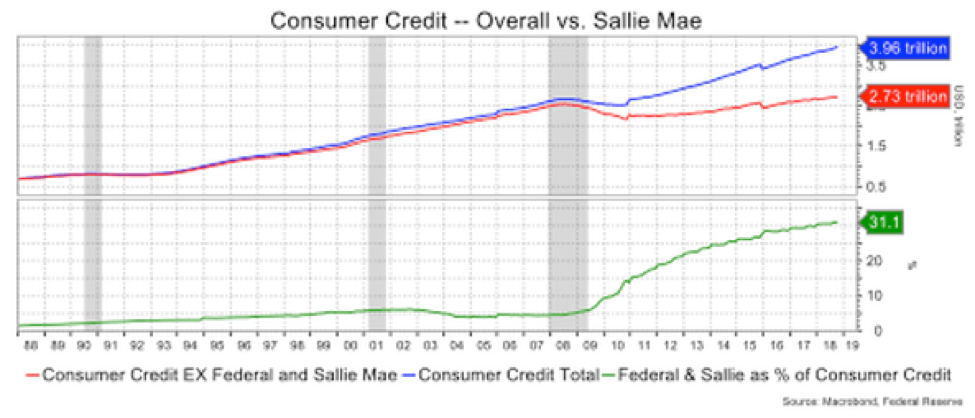

In the movie, Bye Bye Birdie, they sang the song, “What’s the Matter With Kids Today?” I don’t know about what was going on in 1962, but I can tell you the matter today is debt. Students owe about $1.44 trillion in student loans, the delinquency rate is rising on those and it’s been one of the large components to rising consumer credit in general. So, poor kids, have to pay that stuff back which means less money for cars, snowboards, houses, etc.

I won’t argue about the value of a college education, but young people with jobs are burdened by this reality, and there won’t be any relief, except maybe from their parents, which simply pushes the problem up the ladder by now constraining their spending/saving habits.

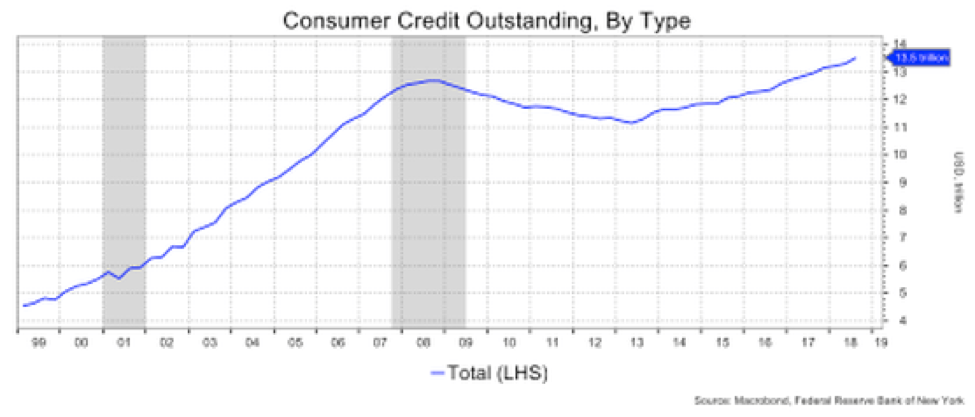

This last chart puts it in a nutshell: total debt as a percentage of GDP. It appears flat, which is a function of less borrowing for mortgages and by federal agencies after the last recession, and, to a degree, more stable borrowing by consumers (think about less home equity lines of credit). If my suspicions are correct, there will be a surge in this measure as a recession causes people to go into debt, and that means coming out of the next recession in worse shape than ever before, which translates to a slower economy for a long while to come.

How do we get out of this in the long run? I suppose we’ll have to accept lower income gains or negative income gains due to higher taxes to pay for some of it, maybe higher inflation, if the government will tolerate it (higher inflation means you’re paying it back in cheaper dollars). I won’t offer grand investment strategies, but assume that cash should hold up, dividend stocks from companies that won’t go out of business should do okay (at least given income) and gold and TIPs offer some allure against the inflation ideas (but not for a couple of years yet). Oh, I’m also thinking about converting IRAs to a Roth, given lowish taxes now and stocks still quite high and worthy of a sale to pay the taxes on the conversion. The idea is that taxes will rise in a few years and a Roth avoids that risk.

David Ader is the former chief macro strategist at Informa Financial Intelligence, and previously held senior roles at CRT LLC and RBS/Greenwich Capital. He was the No. 1-ranked U.S. government bond strategist by Institutional Investor magazine for 11 years, and was No. 1 in technical analysis for five years.