Last week, the bond market received a respite from the ongoing tumult between the Trump administration and, well, just about everyone else. It was a diplomatic trip for the President and a vacation for the rest of us. Call it a hiatus until his budget proposals are reworked (in all likelihood dramatically so) and the investigations start. Both bode to be long developments that continue to leave markets in grand uncertainty.

It amazes me that things marketwise remain quite calm — sideways price action in the grand scheme and low volatility. I don't think it's complacency, but rather a reflection of people not having a big directional call and so staying stable.

I demonstrate little insight to say that into the long weekend and next week's plethora of data — ISM, NFP, Personal Income and Spending, PCE deflators — the market has too much to second guess on a piecemeal basis. Except, that is, for the Fed. In the post-Memorial Day week, the WIRP odds for a June hike are at 100 percent and 83.1 percent for the CME. In this regard, the Fed has all the cover it needs to hike. The data would have to be disastrous to alter those odds to less than even.

There is at least some eyebrow raising that might be warranted. April's core PCE deflator is expected to dip to 1.5 percent with the headline creeping to 1.7 percent. That would be the lowest core rating since last March. Between the hike and inflation data like that, I should be biased for a flatter curve, but the flattening heretofore has pushed the technicals into overbought territory making me wary of chasing it, especially when the hike is so fully priced in.

To dwell a bit more on the charts, if there was a curve play I'd make, I'd be inclined to sell five-year treasury notes versus the wings (see charts at the end). I've seen more compelling patterns to be sure, but momentum measures favor two- to five-years steepening and five- to 10-years flattening. There are also momentum divergences at work in two- and five-years, and two- and 10-years, i.e., MACD and stochastics were rising while the curve was touching new flats.

A Dovish Hike?

I'm not sure this is worth suggesting, but I suspect people will be talking about a dovish hike. That's partly about the inflation data and partly about their want to start talking up the balance sheet as a tool towards normalization. There is no urgent need to sound more aggressive and, surely, the FOMC is pleased with how little turmoil their hikes have been so far. Why rock the boat?

It does seem a bit contradictory to talk about a dovish hike in the wake of the FOMC Minutes that emphasized "transitory" weakness in Q1, an anticipated pickup in inflation to their targets and more hikes and balance sheet reduction. Sill, the Fed has got to be concerned with the market's reaction. And it does seem that balance sheet reduction is coming sooner than many, myself included, originally thought.

In light of recent inflation data and perhaps a bit of diminished confidence about the timing or magnitude of the Administration's fiscal agenda, I think the June hike that's so priced in will be accompanied by the tone of "gradual" especially as they need to prep the market for the balance sheet reduction. The latter is new information and accommodation is warranted.

Growing Pessimism Among Retirees

The thematic of demographics that I've been harping is getting old (I'm sure there's a joke in there). Last week saw an article in the Wall Street Journal that caught my attention and warranted pulling a relevant chart from my presentation on the long-term growth impact of aging demographics. To wit, the WSJ article was titled, “Why Retirees Cut Back on Spending: A Growing Pessimism, It Seems.”

Indeed, in a study by the National Institute on Retirement Security, 72 percent of Americans said they plan to cut current spending to ensure a secure retirement. A Bloomberg article citing the same study made note that the average American over 60 cuts 2.5 percent from their spending per year, or 20 percent over a 10-year timeframe. Their version of this story ran “Rich Retirees Are Hoarding Cash Out of Fear.”

This is hardly a new thing. The chart below shows spending by age cohorts. This ramps up in the household formation years and peters off into retirement; it makes sense. By the time you're retiring, you presumably have bought all the stuff you need, the kids are grown up, you're more content with the furniture you bought, you're driving less and likely you're downsizing. You simply don't need to spend the way you did. Given the growth in the size of older cohorts, the spending as a percentage of total may increase, but behavior patterns suggest that such will be a drag on overall consumption.

Anyway, that WSJ article says older people could spend more — they have the money, at least some do — but it's pessimism that keeps their hands on their cash. “As people age, they become more pessimistic about the stock market, the economy and their own finances,” according to the study they cite. However, that attitude encourages them to safer investing decisions as well. This, too, makes sense. In the last 17 years, they've lived through the NASDAQ bubble, the housing crisis and the financial crisis, which is to say that sometime in their retirement something like one of those could happen again. Of course they're living longer too, and perhaps feel uncertain about the future of entitlements, especially medical care. But it's the pessimism the study seems to emphasize above and beyond the normal prudence of people no longer earning an income.

It's hard to measure this pessimism, or prudence, other than watching spending and investing habits. Again, however, it all makes fiduciary sense; even if retiring and retired baby boomers could spend more than they do, I don't see the injection of confidence that would encourage them to do so. Indeed, the opposite would play in if I were to include the uncertainty generated by Congress and the Administration. Stuff needs to be paid for, right? Maybe these prudent retirees think about the budget deficit.

What are they anxious about? 1) not being able to live a desired lifestyle, 2) not knowing how much they could safely spend, 3) not leaving enough inheritance and 4) dying before they can spend all their wealth.

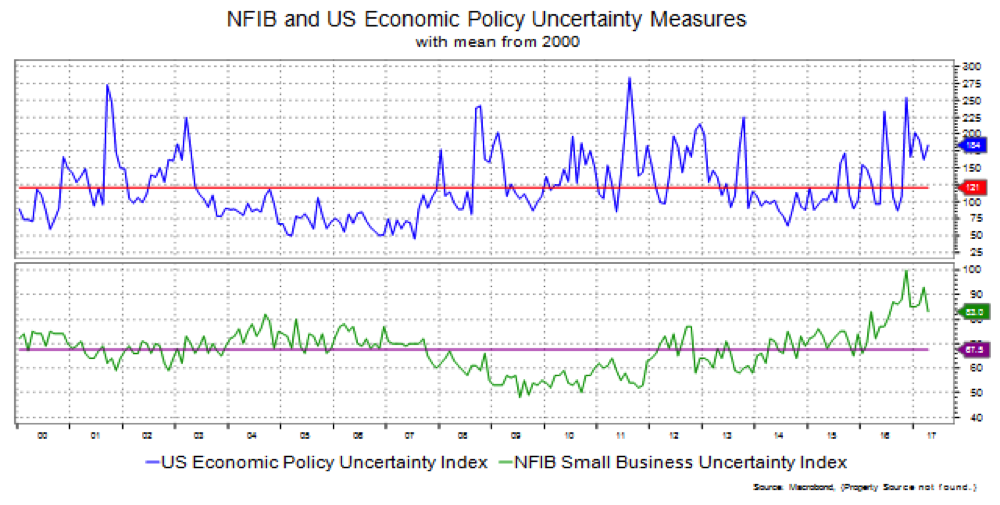

Which brings me to another point I've been talking about: uncertainty. I am by no means the first pundit to note that measures of uncertainty are running high. I know this is not reflected in the VIX and a good deal has been written about that, but here in these soft measures we can readily discern uncertainty. I think it's this uncertainty that's keeping the bond market in a pretty steady sideways range with no discernable longer-term trend in immediate evidence. In this regard, when uncertainty becomes certainty, presumably markets can move either way depending on the conviction.

Hard Data and Soft Data Tell Two Different Stories

What's better — soft measures (like sentiment) or the harder ones (aggregated in something like the Citi Economic Surprise Index or BBG's Surprise Index)?

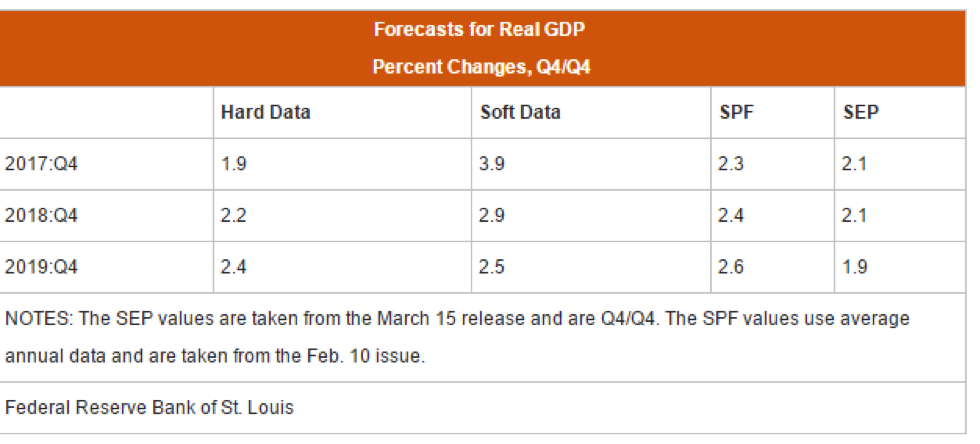

Well the Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis recently posted something on this. Turns out the hard data projects growth at about 2 percent per quarter through the end of 2019 while the soft data looks for a peak of 4 percent in early 2018. Quite a divergence.

Author Kevin Kliesen compared those with the Fed's own forecast from the Survey of Professional Forecasters and the FOMC's Summary of Economic Projections. His conclusion was that the forecasters in question relied more on the hard data as that tends to flow into the macroeconomic models.

He also writes “However, as the upbeat forecasts from the soft data show, there appears to be some upside risk to the near-term forecast for real GDP growth. This upside risk likely reflects the widespread expectation of expansionary fiscal policy and a strengthening in global growth.”

Hmm. So, if the Trump Agenda stumbles on investigations and/or simple pushback from Congress, I presume the forecasts that include some of the fiscal elements will pull back somewhat.

If we do revert to the hard data model's forecast, surely the Fed could lose some of its hawkish bent and line up more with the market's own, less aggressive, anticipation.

EPFR Insights

EPFR is one of the groups in Informa that tracks fund flows in pretty much every market. I will be looking into these more as time goes on but want to tease you with the sort of thing we might uncover.

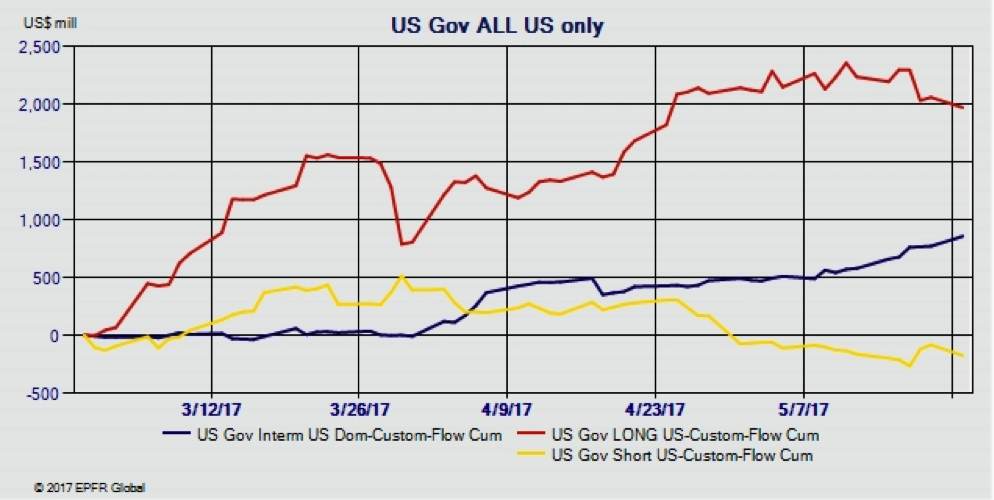

Below you'll see a chart of flows into and out of U.S. Government funds since the start of March on a cumulative basis, specifically for domestic players. The red line shows flows into long-government funds, which you can see has been quite positive. The blue line shows intermediate-fund flows, which is somewhat positive and the yellow line shows flows into short-government funds and is negative. These are at least consistent with the flattening yield curve over the timeframe in question. Ultimately, I'm trying to discern the directional impact, or consistency, of this activity.

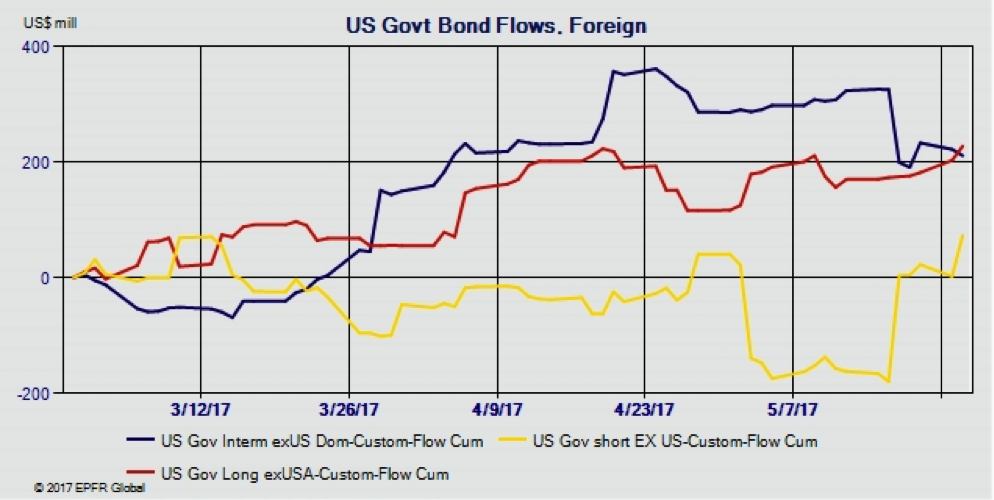

This next chart looks at foreign flows into U.S. Government funds and is somewhat different from the domestic flows displayed above. Here you see the biggest buying flows into long funds, which have been somewhat steadier in recent weeks. Activity in the short end has been flat over the broad time frame though did pick up in the last few weeks, possibly connected to the latest CPI report, though that's rather a guess versus being based on any compelling evidence. It is, however, consistent with the drop in two-year yields since that event.

David Ader is Chief Macro Strategist for Informa Financial Intelligence. To download the pdf version, please click HERE