By Jared Dillian

(Bloomberg View) --The only thing better than getting rich slow is getting rich quick.That bit of truism is all you need to understand the rapid rise in leveraged exchange-traded funds, which were created in 2006 as a way for investors to double their exposure to stock indices. More were created later tied to bonds, commodities, currencies and just about anything else that fund issuers could dream up.

To say that these financial instruments have been popular would be an understatement. As of January, there were 261 leveraged ETFs with $41 billion in assets, or 2 percent of all assets held by ETFs, according to Bloomberg Intelligence. Trading volumes are spinning off into space, and in some cases, in a classic case of the tail wagging the dog, it is the leveraged ETFs that drive the market, not the other way around.

They’re actually a pretty clever financial innovation, as far as financial innovations go: the ETF simply holds a swap agreement with a counterparty such as a bank that agrees to provide two (or three!) times the exposure of the S&P 500 Index, the Nasdaq 100 or anything else. Sounds simple enough, but it became evident fairly early on that these things didn’t behave quite they way people thought they were supposed to behave. Over long periods of time, the leveraged ETF would tend to dramatically underperform the multiple of the underlying index.

So what is going on here? Because of the way leveraged ETFs are constructed, they can only promise two times the daily return of an underlying index. If the S&P 500 goes up 1 percent, the ETF will go up 2 percent -- but only for a day. At that point, the swap has to be rebalanced (which involves some trading activity around the close by the swap counterparty), the leverage is reset, and any overnight holders of the ETF will underperform the index. The difference is often imperceptible at first, but the underperformance adds up over time. A lot.

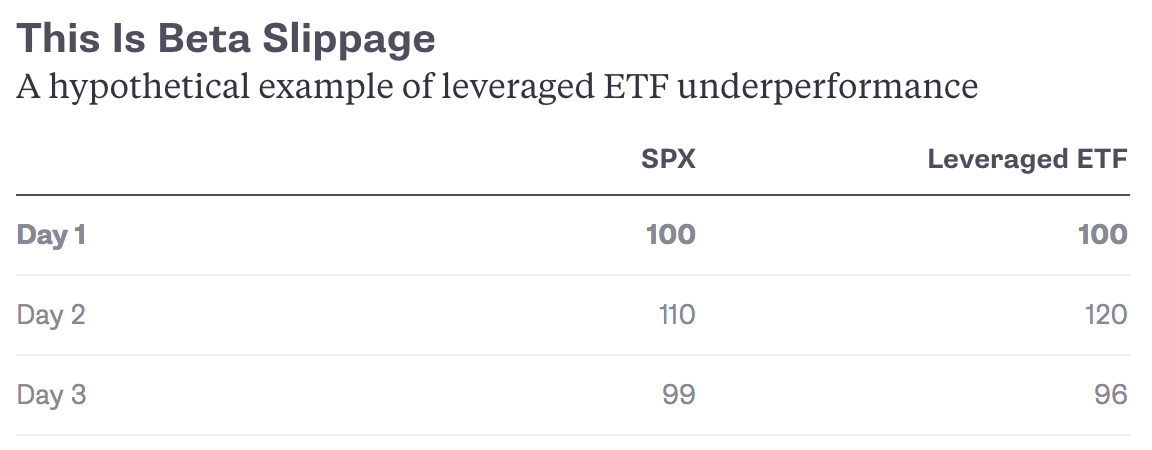

Let’s take the hypothetical example of the S&P 500 index and a 2-times-leveraged ETF that tracks it. On day one, both are at par. On day two, pretend the stock market goes up 10 percent. An unlikely example, obviously, but the math is easier to understand. So, the S&P 500 goes from 100 to 110, and the leveraged ETF does what it is supposed to do — it goes from 100 to 120, delivering twice the daily return.

Then on day three, the market drops 10 percent, sending the S&P 500 down to 99 from 110. The leveraged ETF, however, which started at 120, loses 20 percent of its value and ends up at 96. So after just two days, the ETF has underperformed by about 3 percent. It should be noted that the losses are usually much smaller in practice as they vary with the size of the daily moves.

Issuers of leveraged ETFs are very careful to disclose that the products only deliver 2 or 3 times the daily returns, but how many people read a prospectus? They have been in existence for more than 10 years, and I always hear stories of individual investors finding out the hard way about what the quants call “losses from daily rebalancing,” known colloquially as “beta slippage.” There are many unhappy holders of leveraged ETFs. The issuers will tell you the products are not meant to be held, they are meant to be traded, and on an intraday basis only. But if that were true, then how would leveraged ETFs attract assets under management?

The reality is that leveraged ETFs are super complicated financial instruments --certainly more so than futures, which are linear and plain vanilla because all you have to understand is margining and spreads. In a way, they’re more complicated than options. There’s plenty of math in options, but a closed-form equation describes them. If you’ve ever taken differential equations and statistics, they’re not all that difficult.

The problem with leveraged ETFs is that the losses from daily rebalancing are not easy to quantify. They’re dependent on volatility: the more volatile the underlying index, the more quickly the ETF will “decay.” But there is also autocorrelation risk, meaning there is compounding when the underlying index is up or down several days in a row. The ETFs have taken in $72 billion in new cash since 2006, according to Bloomberg Intelligence, yet their level of assets has stayed about the same because they tend to burn through money in the long term due to the daily resetting of leverage.

Leveraged ETFs are also path dependent in ways that most financial instruments are not. In fact, they’re one of the most complicated derivatives imaginable, especially when you have leveraged ETFs on things like volatility, but they’re easier for retail investors to access than either futures or options.

While retail investors were slow to pick up on the daily rebalancing feature, the quants were not, and what ensued was a giant transfer of wealth from retail investors to professional investors. Professional investors figured out that you could be short leveraged ETFs and actually benefit from the effects of the daily rebalancing. Look, the whole point of Wall Street is to have a transfer of wealth from the unsophisticated to the sophisticated. There is nothing un-American about that. But this is egregious. New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman went after the daily fantasy sports providers, in part, on the same grounds -- the pros were fleecing the punters. It was considered to be excessive. To be fair, the Securities and Exchange Commission did freeze new approvals after warnings from the likes of BlackRock Inc.’s Laurence Fink and Wall Street’s brokerage regulator, the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority.

I was running the ETF desk at Lehman Brothers around 2006 when one of the issuers came by the trading floor to convince us to be authorized participants for the first leveraged ETFs. I saw how these things worked and asked myself, “Are these guys nuts?” Too bad the regulators didn’t feel the same way back then. It's tough to put the genie back in the bottle, but if one were to have perfect knowledge of what was about to happen next, I think the SEC would like to have this one back.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Jared Dillian is the editor and publisher of the Daily Dirtnap and is the author of "Street Freak" and "All the Evil of This World."

To contact the author of this story: Jared Dillian at [email protected] To contact the editor responsible for this story: Robert Burgess at [email protected]

For more columns from Bloomberg View, visit Bloomberg view