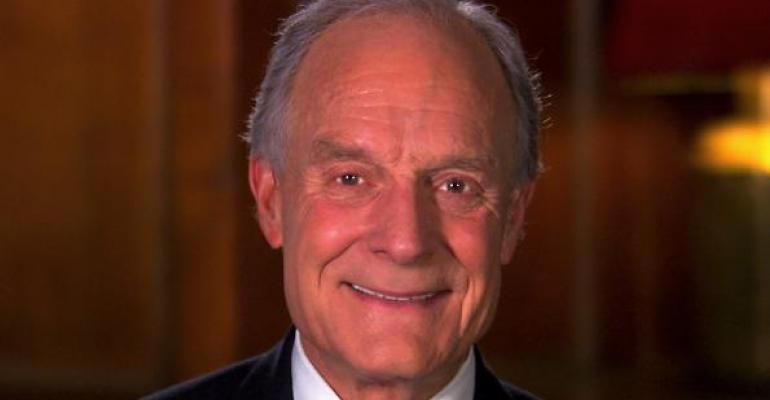

Charley Ellis has been preaching about the benefits of passive investing for a long time. In 1975, he wrote the now-classic article "The Loser’s Game," which challenged the traditional wisdom about the investment business—that professional money managers can beat the market. “That premise appears to be false,” he wrote.

The statement was heretical at the time, but much has changed in the intervening years. Passive investing is widely accepted as a superior approach for the average retirement saver. Indeed, last year, passive investments topped 40 percent of holdings in U.S. equity mutual funds for the first time, according to Morningstar, up from 20 percent 10 years ago.

Now Ellis, who has written 17 books, served as a consultant and investment advisor and professor, is back with a new book assessing the passive landscape—The Index Revolution: Why Investors Should Join It Now (Wiley, September 2016).

You don’t need to read Ellis' books to understand the writing on the wall; the evidence of the superiority of passive strategies for the average investor over the long haul has never been clearer. S&P Dow Jones Indices, which does a semi-annual scorecard tracking the consistency of top-performing mutual funds, reports that very few equity funds consistently stay at the top, especially after five or more years.

Only 7.33 percent of domestic equity funds that were in the top quartile of performance in March 2014 were still there two years later. And just 3.7 percent of large-cap funds maintained top-half performance over five consecutive 12-month periods. For mid-cap funds, the comparable figure was 5.79 percent, and for small-cap funds it was 7.82 percent.

Separate research by S&P Dow Jones finds that most fund managers in nearly every category have underperformed their respective benchmarks over the past five years. For example, 76.2 percent of retail mutual fund managers underperformed the S&P 500 over that time period.

Moreover, more than 80 percent of small-cap fund managers underperformed the S&P SmallCap 600. That finding runs contrary to fund company assertions that the small-cap market is an inefficient asset class and hence requires active management.

I asked Ellis how the active-passive debate looks now compared with 50 years ago when he was beginning his career. “Candidly, back then anyone who was conscientious and hard-working could expect to do better in the market than the averages, although individuals already were being outpaced,” he says. “That is what Winning the Loser’s Game was about—don’t be an individual going out onto a playing field where everyone else is from the NFL and you are going to be outclassed.”

Since that time, the industry’s changed structure has reversed that dynamic. As he notes in the book:

- Trading volume on the New York Stock Exchange increased from three million to five billion shares daily over the past 50 years.

- The dollar value of trading in derivatives rose from zero to more than the value of the cash market.

- Trading by individuals has been overwhelmed by institutional and high-speed machine trading, now representing 98 percent of all trading.

- The 50 most active professionals (half of them hedge funds) do 50 percent of all NYSE-listed stock trading.

“When I first got involved, the secret sauce of active investing was that you could go to the companies that you were interested in, and senior executives were thrilled to have the opportunity to talk with you because they wanted to let investors know what they were doing,” he says. “So you would learn an enormous amount and you could make comparative judgments that were well-informed.”

“Now, the SEC requires any public companies to disclose information to all investors simultaneously, so that obliterates the secret sauce. There are almost one million investors actively involved in trying to find pricing errors—50 years ago there were 5,000.

“Everyone has access to information; they are all smart and aggressive—and they may not be perfect but awfully good. So mistakes don’t last long and they can’t get very big.”

Fees pose another key hurdle for active managers. The drag on performance is well documented. “One percent of assets doesn’t sound that bad until you consider that as a percentage of returns—if we are assuming a seven percent return on equities, that’s 14 percent of returns.”

The high “death rate” among active funds is another nail in the coffin. S&P Dow Jones reports that across all market cap categories, about one-third of equity funds in the fourth quartile were liquidated or merged over the last five years. In the book, Ellis notes that “there’s a painful sting in the tail” from funds that close: They tend to decline sharply in their last 12 to 18 months—3.98 percent in the last 18 months, 2.47 percent in the last 12 months.

The high mortality rate poses a range of problems for investors. They often are forced to sell at depressed prices; if the funds are held in taxable accounts, investors could receive capital gains distributions and owe taxes, even if the holdings were purchased before the fund was owned. There could also be liquidation expenses.

Ellis has nothing but admiration for active money managers. “I know the people involved—they are good guys, but they have gotten themselves into an ethics trap,” he says. He hopes “many remarkably capable and hardworking investment professionals will find this short book a wake-up call to redefine their responsibilities and real purpose of their work.”

I asked him to elaborate on that hope, especially the role of financial advisors. The big opportunity for advisors, Ellis thinks, is to shift from focusing on stock-picking to a more holistic approach to advising clients.

“It really changes the nature of your responsibilities, from picking the manager who will do better, the advisor who will sit with a client and help that client by asking sensible adult questions and to recognize who they really are, will do well. What are their wealth, their future income and their future spending needs? What is the family’s longevity history? How many children do they have, and what kind of legacy requirements do they have?”

That kind of approach to advice also is at the heart of the new fiduciary requirements now being rolled out for retirement advisors by the U.S. Department of Labor. Taken together, the market’s move to passive and the DOL rule point strongly toward a new focus on overall financial health, and much less on stock-picking.

Or to use one of Ellis’ favorite quotes, from Winston Churchill: “You must look at facts, because they look at you.”