You may have noticed that oil prices have soared recently. Oil exchange traded funds have topped the charts this year by wide margins. Unfortunately, many investors shun oil ETFs for fear of the commodity markets. Some equate commodity trading to gambling.

This equation is unfounded. There’s a distinction between gambling and speculation. A broad economic purpose is served by commodity speculation. Gambling? Not so much. Speculation keeps prices for staples – such as bread, meat and gasoline – low. Or lower than they would be without a futures market.

Producers and users of commodities constantly square off against price risk. Take an oil refiner as an example. An independent refiner such as Valero Energy Corp. buys crude oil on the open market to process into gasoline and other distillates for subsequent sale. Valero’s profit margins are at risk from both sides of its refining cycle. Rising crude costs and/or falling distillate prices could put the squeeze on the company’s earnings.

Look at the input side. Valero can hedge the risk of rising crude costs in a number of ways, one of which is to use the oil futures market. Buying oil futures contracts ahead of the company’s intended need essentially locks in the firm’s supply cost. If crude market prices rise, the value of Valero’s futures contracts also increases, providing a profit that can be used to offset higher cash prices when the refiner ultimately takes an oil delivery. While hedged, Valero has two crude oil positions: long futures and short spot. These positions more or less offset each other, transforming the once-large cash market price risk into a smaller, more manageable and predictable risk in the basis – the difference between the futures and cash prices.

So, who sells the oil contracts to Valero? Speculators. Traders who think oil prices may actually fall during the tenure of their contracts. Speculators, having only a short futures position, take on the entirety of the price risk Valero seeks to shed.

Hedgers transfer price risk to speculators through the futures market. By hedging, Valero can better manage its input costs, which, in turn, helps to keep its margins and end-product prices more stable.

Gamblers don’t fulfill such an economic purpose. The risk they accept when they walk up to the green felt tables doesn’t stabilize market prices for others. Any benefit inures entirely to the gambler.

That brings us to the gambling house’s “edge,” the built-in advantage for every game, to keep it in business. The longer you play, the more likely the house will earn its edge from you. That’s why they keep you at the tables with free booze and other “comps.”

Buying certain futures for the long term can also subject you to an edge of sorts. It’s called contango – the premium at which more distant future deliveries trade over those closer. Case in point: Let’s say crude oil for May delivery changes hands at $62 a barrel. If June crude simultaneously trades at $63 a barrel, there’s a $1 contango. Contango’s made up mostly of the storage and insurance costs incurred when holding a commodity for future delivery. Contango persists when there’s an ample supply of a storable commodity. A backward or inverted market – one in which the nearby contract is priced at a premium over the more distant future one – develops when that same commodity is in short supply.

To illustrate the impact of contango, let’s suppose you believe oil will rise over the next year. Buying the nearby May contract gives you exposure to the spot price, but that exposure will expire when the May contract goes off the board. To keep your long position in spot oil, you’ll need to roll your futures position forward before the May contract’s delivery period. You’ll need, in other words, to sell the expiring May contract and buy the next-out June contract. With the futures curve described above, you’d incur a $1 per barrel transaction cost—the contango—by doing so. If your cost basis in the May contact isn’t low enough, the contango could eat up any gains you might have earned from appreciation in the May contract price. In the worst case, you might suffer a net loss when you roll forward.

That’s exactly the problem currently faced by investors in the United States Oil Fund (NYSE Arca: USO). This popular exchange traded fund tracks the spot futures price of light, sweet crude so it’s constantly rolling its long position forward. That makes the fund exquisitely sensitive to the shape of the futures curve. That’s a vexation for investors who look to oil as an inflation hedge. (While gold has traditionally been thought of as an inflation hedge, history indicates that oil is better correlated to the Consumer Price Index than bullion. Three times better, in fact. This makes sense since oil and its distillates contribute directly to consumer costs.)

Oil’s contango cost can be significant. This year, though, that cost has been relatively modest. Through the first week in April, spot WTI (West Texas Intermediate) gained nearly 39%. Investors holding USO shares have given up almost 3% of that gain in rolling costs. Sometimes, contango’s toll is higher, especially so when oil prices decline. In 2017, the last year that began with a contango, crude’s price slumped 4.8% by the first week in April, but USO holders suffered an 8.6% loss. The previous year started off even worse. WTI slipped 3% over 2016’s first quarter, but the forward roll over a very steep futures curve ended up costing USO owners an additional 14%.

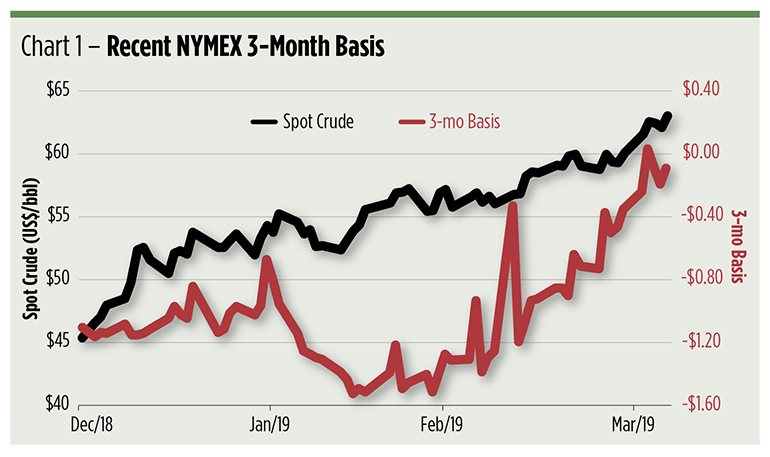

By now, you’re probably sensing the fluidity of the futures curve. Contango constantly ebbs and flows, mostly driven by supply. Chart 1 depicts this year’s market for spot crude plotted against the 3-month basis. Basis is calculated by subtracting the deferred contract price from the nearby or spot price. As such, the basis will be negative when the market’s in contango and positive when the market’s inverted.

As you can see, this year’s basis – in this instance a contango – has ranged significantly and most recently flirted with backwardation.

In fact, contango is often replaced by backwardation. When distant deliveries are priced below nearby contracts, there’s actually an advantage gained with a forward roll. An inverted market is a boon to USO fund holders, augmenting gains earned by appreciation in crude oil’s price or mitigating losses when WTI declines over a contract’s holding period. This played out in 2018. Spot WTI prices edged up 5.2% through the first quarter of an inverted market, but owners of the USO fund enjoyed a 6.8% gain. Thus, backwardation bestowed a 1.6% benefit to holders of the fund.

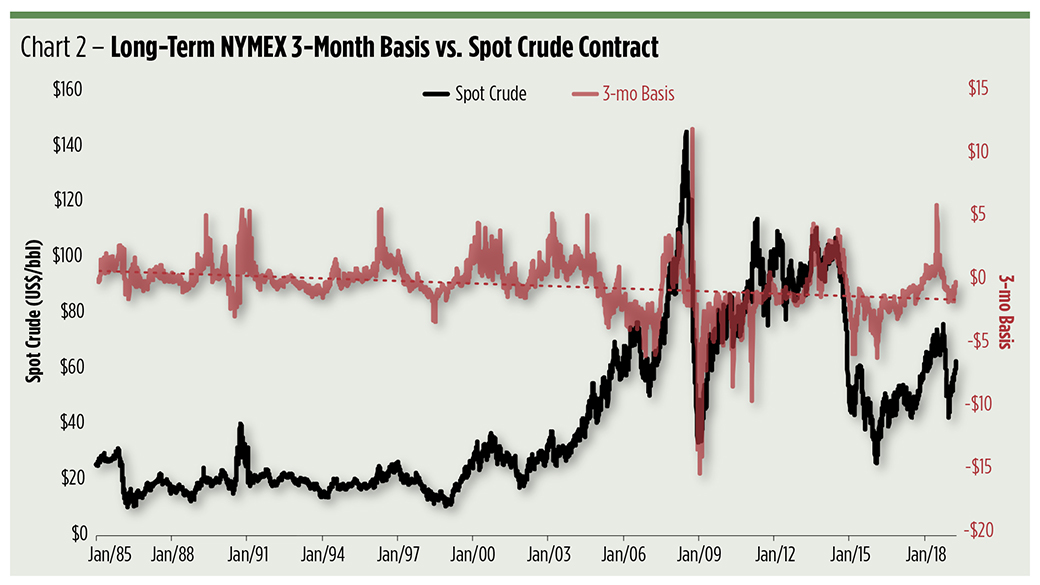

So, how often does the oil market spend in backwardation? The quick answer is “a fair amount.” As of this writing, futures, measured by the 3-month basis, have been in contango for 115 trading days. The previous backwardation cycle, which ended inOctober, lasted 211 trading days. Over the longer term, the market’s spent as much time in backwardation as it has spent in contango. Pricewise, though, contango’s a more potent force. Well, a slightly more potent force. Since 1985, the average state of the 3-month basis is a 14 cent contango. But, as Chart 2 shows, the price spread’s been pretty volatile, ranging from a $12 inversion to a $15 contango.

The important takeaway from Chart 2 is that dotted red line. It’s the exponential trend line for the basis, and it’s headed southward. An exponential trend line places more emphasis on recent pricing. What’s being reflected here is the oversupply of oil as domestic production has ramped up.

The consequence? As long as the U.S. keeps producing prodigious supplies of crude, contango’s likely to stick around. Or, at least deepen when it reappears. And that means long-term oil investors, or inflation hedgers, need to consider ways to lessen their forward roll risk. Luckily, there are three exchange traded funds that offer strategies to minimize contango’s depredations.

USO’s sister fund, the United States 12-Month Oil Fund (NYSE Arca: USL) takes positions in each of the 12 upcoming delivery months rather than loading up on just the spot month.

The Invesco DB Oil Fund (NYSE Arca: DBO) optimizes its oil exposure with an algorithm that rolls into the most attractive contract month, i.e., the delivery with the best roll yield over a 13-month horizon, rather than mechanically buying the next-forward month.

And then there’s the actively traded ProShares K-1 Free Crude Oil Strategy ETF (BATS: OILK), which empowers its managers to select a forward roll target within the upcoming three delivery months.

We’ll compare these alternative ETFs in depth in future columns. Stay tuned.

Brad Zigler is WealthManagement's Alternative Investments Editor. Previously, he was the head of Marketing, Research and Education for the Pacific Exchange's (now NYSE Arca) option market and the iShares complex of exchange traded funds.