“Without a guru, none can cross over to the other shore.”

A bit of self-promotion by 15th century philosopher Guru Nanak seems forgivable. After all, there wasn’t an internet in his day. Today, a guru’s advertising reach is much broader, especially for financial gurus. Some aggressively market their genius; others’ reputations are burnished by third parties. No matter how their horns may have been tooted, the standing of some money maharishis has endured for several market cycles. Among them are Bill Bernstein, David Swensen, Harry Browne and Larry Swedroe.

More than a few investors and advisors owe their introduction to asset allocation to Bill Bernstein, an Oregon-based neurologist and financial theorist. Bernstein’s seminal book, The Intelligent Asset Allocator, argues that most investment returns are determined by asset allocation rather than stock picking or market timing. In a raft of subsequent books, Bernstein suggested several portfolios for individual investors, the most widely subscribed of which is the “no-brainer”—one-quarter U.S. large-cap stocks, one-quarter U.S. small-cap stocks, one-quarter global (ex-U.S.) stocks and one-quarter U.S. bonds.

David Swensen has been the chief investment officer at Yale University since 1985 and manages the university’s $27.2 billion endowment. Swensen’s investment approach, known as the Yale Model, seeks equity-like returns without heavy reliance on equities themselves. During Swensen’s tenure, the Yale Endowment’s mix of non-traditional assets have consistently generated annual returns in excess of its benchmark and institutional fund indexes. Swensen’s 2005 book, Unconventional Success, boiled down his investment approach for the individual investor. With an eye toward cost control, Swensen proposed a six-asset portfolio, made up of exchange traded funds tracking U.S. and international stocks, emerging market equities, conventional and inflation-protected Treasury securities and real estate investment trusts.

The so-called “permanent portfolio” investment strategy is credited to writer, politician and investment advisor Harry Browne. In his 1999 book, Fail-Safe Investing, Browne identified four sets of economic conditions operating in a given investment period with an asset mix aimed at maximizing profit and minimizing loss over the long term. In its simplest form, the permanent portfolio is built on equal allocations to U.S. stocks, long-term Treasury paper, gold and cash. Browne ultimately served as a consultant to the Permanent Portfolio Fund (OTC: PRPFX) which utilizes some of the investment strategies described in his book.

Larry Swedroe is a St. Louis-based principal and director of research for Buckingham Strategic Wealth and the author of eight books on personal finance and investing. His 1998 book, The Only Guide to a Winning Investment Strategy You’ll Ever Need, explained the science of investing in layman’s terms and advocated the use of index funds to build diversified portfolios. Swedroe’s basic approach has evolved into a six-class portfolio including U.S. large-cap, small-cap and small-cap value stocks, international (ex-U.S.) value stocks and emerging market stocks, together with U.S. Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities.

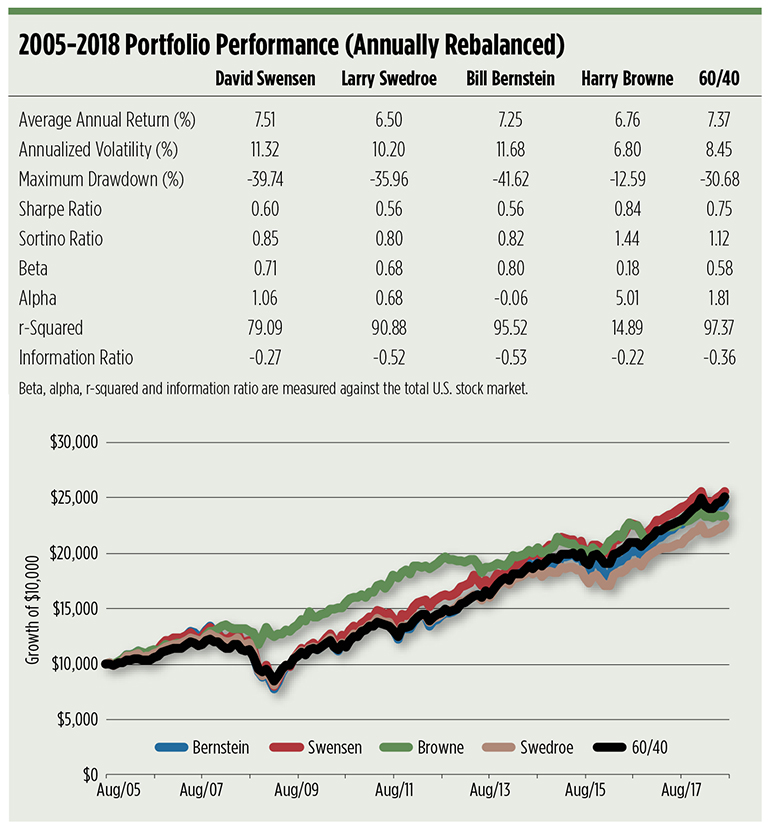

So, which of these financial gurus has advanced the best investment thesis for individual investors in today’s market environment? To determine this, we ran simulations of their signature portfolios using readily available index funds and grantor trusts, annually rebalanced from September 2005 through July 2018, and put them up against a classic “60/40” portfolio of U.S. stocks and broad market bonds.

David Swensen. Over the past 13 years, Swensen’s approach yielded the highest compound growth rate at the cost of higher-than-benchmark volatility. The portfolio’s relatively low r-squared coefficient bespeaks a fair degree of diversification away from U.S. stock market risk. Still, Swensen’s retail portfolio includes a significant allocation to domestic equity.

| U.S. Total Stock Market | 30% |

| International Developed Market (ex-U.S.) Stocks | 15% |

| Emerging Market Stocks | 5% |

| Long-Term U.S. Treasury Securities | 15% |

| U.S. Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities | 15% |

| Real Estate Investment Trusts | 20% |

Across a number of other metrics, Swensen’s portfolio is second best versus Harry Browne’s permanent portfolio. Most notably, the Yale Model’s information ratio is just a few ticks off the Browne allocation. The information ratio, one of the toughest hurdles for a manager to clear, measures not only the degree by which a portfolio outperforms its benchmark but also its consistency. A positive information ratio is earned when the portfolio demonstrates an ability to outdo its benchmark for some period of time. A negative ratio signifies a portfolio with an undependable record of outperformance. Or no outperformance at all. In this sense, the information ratio goes beyond the alpha coefficient which measures a portfolio’s excess return over its beta-adjusted benchmark.

Larry Swedroe. The value and small-cap factors take a front seat in Swedroe’s allocation or rather they refuse to take a back seat to the large-cap growth factor that dominates total equity market indexes. His portfolio is actually a variant of the 60/40 approach, though the fixed income slot is filled with TIPS rather than traditional coupons.

| U.S. Large-Cap Value Stocks | 15% |

| U.S. Small-Cap Stocks | 13% |

| U.S. Small-Cap Value Stocks | 15% |

| International (ex-U.S.) Value Stocks | 13% |

| Emerging Market Stocks | 4% |

| U.S. Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities | 40% |

The relatively large allocation to fixed income dampens the standard deviation of the portfolio’s returns, at least compared to the Swensen approach, though other volatility metrics—the Sharpe and Sortino ratios together with the beta coefficient—are within a hair’s breadth of Swensen’s. Swedrow’s approach notches the lowest average annual return, making it considerably less alpha efficient. This underperformance is largely due to the portfolio’s value tilt, a factor emphasis that was out of favor for much of the study period.

Bill Bernstein. If there’s one word that describes Bill Bernstein’s approach it’s “simplicity.” It’s the four-bean salad of portfolios, serving up equal dollops of U.S. large- and small-cap equities, foreign stocks and domestic broad market bonds. There’s not much spice in Bernstein’s mix to mellow its inherent volatility. Witness the allocation’s maximum drawdown—the deepest and longest of all the portfolios.

| U.S. Large-Cap Stocks | 25% |

| U.S. Small-Cap Stocks | 25% |

| International (ex-U.S.) Stocks | 25% |

| U.S. Total Bond Market | 25% |

While Bernstein’s portfolio offers a nominal growth rate close to that of the benchmark, the no-brainer mix significantly underperforms on a risk-adjusted basis.

Matching Bernstein for simplicity, Harry Browne’s approach can best be described as “winning by not losing.” With four widely diverse assets, the permanent portfolio underperforms the benchmark on a nominal basis but leaves the 60/40 allocation—and the other gurus’ mixes—in the dust on a risk-adjusted basis. Most notably, the Browne portfolio’s Sortino ratio skunks the other asset mixes. The Sortino metric, like the Sharpe ratio, gauges a portfolio’s excess return against its volatility but only uses downside variance—the “bad” volatility—as a divisor.

| U.S. Total Stock Market | 25% |

| U.S. Long-Term Treasury Securities | 25% |

| Gold | 25% |

| Cash | 25% |

The portfolio’s protective posture is made manifest in its maximum drawdown—fully an order of magnitude less than the other allocations. It’s precisely for this that Browne dubbed it a permanent portfolio.

To the Other Shore

Our analysis shines a light on two portfolios for their outperformance. First, there’s the Swensen mix which earned the highest average annual gain. Then there’s the Browne portfolio for its risk control. Which approach is more likely to get you to your investment goal? The answer to that question largely depends upon your faith and your time horizon. If you believe that the equity bull market still has legs, the Yale Model’s probably going to give you more bang for your volatility buck. If you’ve got a longer investment horizon or you’re uncomfortable with equity market risk, then you’re better off considering the permanent portfolio route.

Brad Zigler is WealthManagement's Alternative Investments Editor. Previously, he was the head of Marketing, Research and Education for the Pacific Exchange's (now NYSE Arca) option market and the iShares complex of exchange traded funds.