Assessing the suitability of a buyer for your wealth management practice and negotiating the terms of the transaction are merely a seller’s early steps in “monetizing” the value of the business. In this series of articles, I’ll be examining how buyers and sellers can work together to minimize client attrition during these often-difficult transitions.

While your clients may be happy for you as you move toward your retirement vision, they are not necessarily going to be happy or comfortable with the disruptions to their portfolios and the accompanying discomfort of being delivered over to another wealth management firm that was, most likely, unknown to them prior to your merger.

Once the merger documents are signed, the seller’s primary mission becomes helping the former clients develop a sense of trust in the new firm within the time frame of the negotiated payout period. Success in this endeavor requires that the seller identify longer-term potential risks to the transaction and devise a series of strategies, agreed to by the buyer prior to the merger, to increase the probability of client longevity during and after the payout period.

First, it’s key to recognize that you have made assumptions about events that will be unfolding over the ensuing years of your payout period. What you have created with your merger partner is simply a projection of future revenues to both of you. Projections about the future are fragile. Most will not unfold as you have imagined.

Chief among your assumptions is that over your payout period, and with your guidance, your former clients will develop enough confidence with the buyer to remain not only during your payout period but afterward as well. You and the buyer will likely have different ideas about how investor trust can be earned. This thought calls for the joint development of a written client retention plan as part of the merger documentation. By creating such a document, both parties to the transaction can flesh out many of the issues that might (will?) otherwise arise after the closing that ultimately impede the development of client trust in the buyer’s firm.

Some examples of seller risk assumptions may include:

- No recession and market selloff during the transaction payout period;

- continuation of seller’s staff as employees of the buyer’s firm;

- not more than X% of your clients become deceased;

- not more than Y% of AUM is lost to attrition for any reason;

- unlimited client communication and visitation rights continue;

- you don’t die or become disabled thereby rendering you incapable of facilitating the trust-building process;

- you have the authority to veto the inclusion or disposition of certain products or securities in client portfolios; or

- the buyer’s organization continues intact throughout the payout period.

Fragility: The Big Picture

Virtually all of the articles I have seen, and the consultants I have spoken with, are focused on guiding a seller to extract the maximum value from a sale or merger, while acknowledging that there will be a degree of transition risk that will likely reduce the seller’s ultimate payout amount. In my case, the valuation consulting firm I retained estimated that I might receive perhaps 90% of my negotiated amount over my payout period. In fact, when the final transaction terms are agreed to, the seller has identified pretty much the maximum amount receivable from the transaction. Under this typical merger structure, the transaction can be observed to have an asymmetrical payoff where downside risks are potentially significant, and upside financial potential is most likely nil.

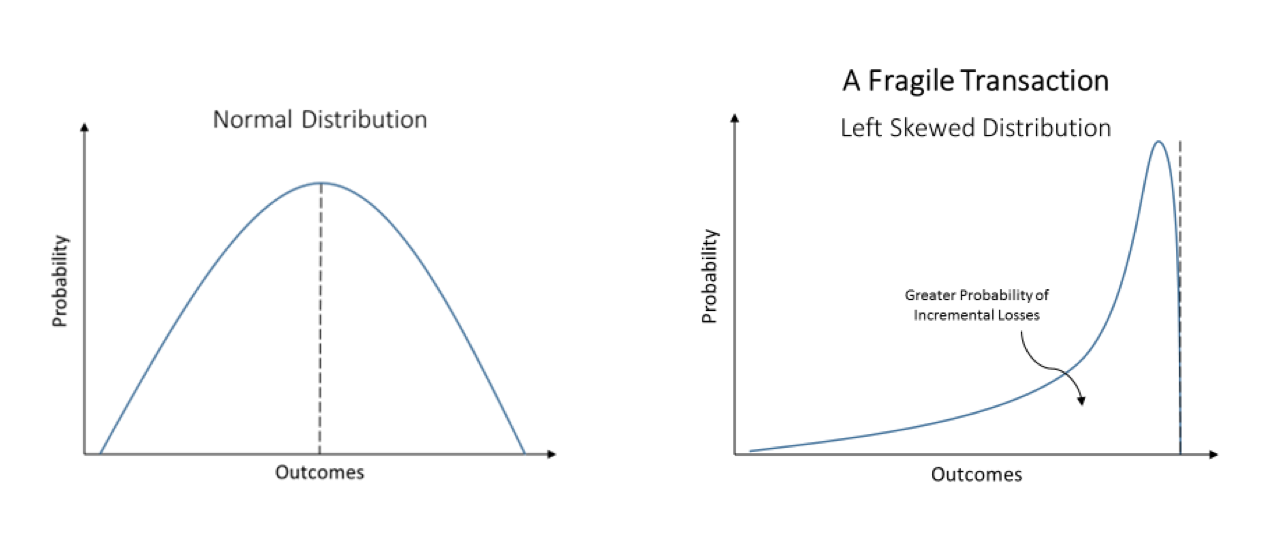

Nassim Nicholas Taleb, in his book Antifragile, aptly illustrates the nature of the transaction risk typically taken by a disengaging seller. He distinguishes between entities or situations that may succumb to adverse events resulting in costly negative outcomes, versus those situations that may actually benefit from future adversity. This latter condition of benefiting from adversity is characterized by Taleb as being antifragile. His concept got me thinking about the structure of transactions involving efforts by sellers seeking to transition their clients to a new firm while scaling back their management activities into eventual retirement. By looking at the sale of an advisory practice in terms of a fragile/antifragile framework, it becomes easier to identify aspects of a transaction that will create an asymmetrical probability distribution in which the downside risks to a successful outcome greatly exceed the possibility of upside incremental reward. This situation can be graphically illustrated as follows:

The asymmetrical appearance of the probability chart on the right depicts the fragile nature of the transaction. Examples of negative outcomes that can reduce a seller’s payout easily come to mind:

- Greater-than-anticipated client death rates and other demographic issues;

- higher-than-expected rates of cash distributions from client portfolios;

- failure of clients to develop trust in the buyer’s organization, staff or philosophy of portfolio management leading to eventual client departures;

- cultural clashes between the seller’s and buyer’s staff resulting in seller staff departures;

- client annoyance with taxes generated from portfolio repositioning into the seller’s management style;

- poor portfolio performance during the transition period relative to an applicable benchmark;

- perceived conflicts of interest at the buyer’s firm not previously experienced at the seller’s firm;

- a bear market;

- clients generally reappraise their financial service needs and conclude the new firm doesn’t measure up to available alternatives;

- unsatisfactory client/service rep rapport;

- a data breach after the merger;

- the buyer sells out to, or merges with, a larger firm during your payout period with attendant staff disruptions;

- difficulty creating a relevant transition period benchmark leading to performance dissatisfaction;

- clients perceive themselves to be of diminished importance in the buyer’s larger organization; or

- the buyer experiences regulatory breaches of conduct that become known to clients.

Needless to say, the list of things that could feasibly go wrong over which the seller himself has little control is expansive.

Sellers should think about these and other possible risks that originate with the buyer and contemplate how to incorporate options for dealing with such events into their merger agreements.

In part 2, we’ll address some of the more active steps both buyers and sellers can take to retain clients during a transition.

Any comments and/or questions regarding the article can be directed to me at [email protected].

Roger Sheffield, CFA, has been a portfolio manager and investment counselor since 1975. He has owned and operated his own RIA firm for most of this period and ultimately sold that firm to another RIA in 2017, at which time his firm’s assets under management were approaching $100 million.