In the first installment of this series, I introduced a model, “The Path of Most Resistance,” which illustrates why a good estate-planning result is so hard to achieve. In the next installment, I discussed three psychological phenomena that one can witness in estate planning. In this final installment, I discuss death anxiety, the issue of mortality salience (reminders about death)1 and common fears that clients face in estate planning. I’ll conclude this installment by introducing estate planners to two tools that can assist them in the human side of estate planning: motivational interviewing (MI) and appreciative inquiry (AI).

Death Anxiety

“Death anxiety” is defined as:

. . . a complex phenomenon that represents the blend of many different thought processes and emotions: the dread of death, the horror of physical and mental deterioration, the essential feeling of aloneness, the ultimate experience of separation anxiety, sadness about the eventual loss of self, and extremes of anger and despair about a situation over which we have no control.2

These fears can cause people to act differently, even irrationally, from how they typically would under different circumstances. These actions often lead to conflict because the survivors joust for a piece of the decedent’s property, persona or symbolism, which people seek to assuage their fears and comfort themselves for their loss. Psychologists posit that all humans develop an innate ongoing existential fear of death from a relatively early age.3

Psychiatrists have determined that there are at least seven reasons why people have death anxiety:4

1. No more life experiences.

2. Fear of what will happen to their bodies post-death.

3. Uncertainty as to fate if there’s life after death.

4. Inability to care for their dependents.

5. Grief caused to relatives and friends.

6. All their plans and projects will come to an end.

7. The process of dying will be painful.

There are at least three defenses that individuals commonly employ to withstand death anxiety:

1. Avoidance of talk about mortality and other reminders of mortality (called “mortality salience”).

2. Minimization of mortality through jokes about death and feeling that the concern about mortality isn’t pressing enough for action at the moment.

3. A desire for symbolic immortality, which is a form of autobiographical heroism, in which individuals take actions that solidify and perpetuate causes and provide for those who are important to them.5

Mortality Salience

Estate planning causes people to face their own mortality. Mortality salience plays a role in estate planning by often causing people to put off their estate planning for another day, despite its apparent glaring need in particular situations. According to the research of Dr. Russell N. James III, the forms of avoidance of mortality salience are:

• Distraction: “I’m too busy to worry about that right now.”

• Differentiation: “It doesn’t apply to me because I come from a family of actuarial longevity.”

• Denial: “These death worries are overstated.”

• Delay: “I plan on worrying about death…later.”

• Departure: “I’m going to stay away from death reminders.”6

According to the research, mortality salience causes increases in the following:

1. Desire for fame.

2. Perception of one’s past significance.

3. Likelihood of describing positive improvements in writing an autobiographical essay.

4. Interest in naming a star after one’s self.

5. Perceived accuracy of a positive personality profile of one’s self.7

According to Dr. James and his research, mortality salience results in a greater attachment to and support of one’s community’s values over an outsider’s values. This includes an increase in:

1. Charitable contributions by U.S. donors to U.S. charities over foreign charities.

2. A predicted number of local NFL team wins.

3. Negative ratings by Americans of anti-U.S. essays.8

According to Dr. James, external realities occasionally break through avoidance of mortality salience, including illness, injury, advancing age, death of a close friend or family member, travel plans and intentionally planning for one’s death through estate planning, which cause people to tend to their estate planning. However, these external realities are unpredictable and sporadic.9 But, the issue of procrastination and avoidance in estate planning is far more complex than just avoidance of mortality salience.

Fears of Estate Planning

People have at least 12 fears about estate planning, of which death anxiety is but one. They fear:10

1. Contemplating death (death anxiety).

2. Not doing the right thing.

3. The unknown.

4. Hurting someone’s feelings/creating animosity/post-death squabbles.

5. Estate planners.

6. The estate-planning process.

7. Running out of money/losing security.

8. Changes in the law.

9. Facing reality.

10. Loss of flexibility.

11. Loss of privacy.

12. Probate.

Most of these fears are irrational and can be safely and properly addressed in a well-confected estate plan. Estate planning has therapeutic and anti-therapeutic consequences, the latter of which the estate planner must identify and work to ameliorate.11 Estate planning, once done and finalized, is known to reduce death anxiety, for example, recall Ishmael from Moby-Dick about his will signing.12

Effects of Death Anxiety

Death of a loved one or a friend conjures up two fears in most of us: 1) the loss of a source of safety and security; and 2) a fear of our own mortality.

This often causes a split in the ego,13 as people trick themselves through a cognitive distortion14 into thinking that their own death isn’t something that they need be concerned about at present. This typically results in repression of thoughts of death, as they’re simply too painful to be allowed into a person’s consciousness. The splitting of the ego can lead to depression and other forms of psychosis as well as the loss of internal object ties.15

Here are two examples of cognitive distortions:

• People often compare themselves to individuals who are known to have abused their bodies, for example, Keith Richards, and say that if he can live that long after having done what he did, they’ll survive too until at least his age or older.

• Older persons, whose death is more imminent, focus on medical research or make deals with themselves to get healthier, and, by so doing, think they’ll live longer.

One potential consequence of death anxiety is the deterioration of the testator’s decision-making capabilities. The fear forces people into making short-sighted or ill-advised decisions that will have a lasting impact on their loved ones. Fear of making these types of bad decisions also flows out of death anxiety, as people are reluctant to act on their estate planning for fear that they’ll make a bad decision. People often cope with death anxiety by making difficult decisions quickly, thereby abbreviating the stressful experience.16 These swift decisions often are bad ones.

This oft-truncated decision-making process usually involves an erratic method of selecting information for consideration, an inadequate amount of time spent considering that information and evaluating alternatives and a lack of willingness to re-evaluate after the decision is made. Getting it done is more important than how or what was done.17

Humans are the only species who know cognitively that life is finite and that we’re mortal. However, that cognitive knowledge, combined with the desire to procreate and survive, create what Mario Mikulincer, Victor Florian and Gilad Hirschberger call “an irresolvable existential paradox.”18 A human’s survival mode causes him to put off thoughts of his own demise because survival is the goal, despite clear signs of eventual mortality. Hundreds of studies have proven that when confronted with mortality salience, humans adhere even more passionately to their view of the world.19 Humans resort to lots of methods to avoid the fear brought on by mortality salience, including religion, work, relationships, exercise and wealth accumulation.

Terror management theory20 (inspired by the work of Ernest Becker21 and Otto Rank) instructs that humans grasp for any kind of immortality to cope with mortality salience, including symbolic immortality. Symbolic immortality includes our belief in an afterlife, our descendants, our favorite institutions and our body of work, wealth and accomplishments. Estate planning properly done gives clients symbolic immortality.

Separation anxiety, which is articulated in attachment theory, also contributes to inheritance conflict. Attachment theory was formulated in the 1930s by John Bowlby, a British psychoanalyst who worked with troubled children. It postulates that infants will go to great lengths, for example, crying and clenching, to prevent being separated from their parents. Attachment theory has been extended to adults and goes a long way to explaining why adults do what they do when a loved one passes away.22 Grieving loved ones often scramble for and squabble over items that symbolically resemble the decedent’s persona or successes to which they can remain associated, for example, grandma’s china, dad’s watch or family portraits. The financial value of these items is often irrelevant.23

According to the late clinical psychologist Edwin Schneidman, the closest that most people get to acknowledgment of their own mortality is a view of the world after our death and how we’ll be remembered—which he called the “post-self.”24 Schneidman viewed each person’s property as an extension of one’s self, which is in line with Jean-Paul Sartre’s famous quote, “The totality of my possessions reflects the totality of my being. I am what I have. What is mine is myself.”25 Estate planning often is viewed as one of the last opportunities to foster one’s post-self.26

As mentioned previously, estate planning, once faced, confers a form of symbolic immortality on the testator, who in essence gets to continue to influence and participate in the lives of the beneficiaries after death. But, fewer than half of Americans make a will.27 Why? Fears of estate planning for most exceed the purely psychological payoff of symbolic immortality and peace of mind.

Reasons for Inheritance Fights

A common reason why some people don’t engage in estate planning is a fear that their families will fight after their death, when their motives and activities will be subjected to unwanted intense public scrutiny. Because it provides a medium for the public airing of the “dirty laundry” and family secrets of testators and their families, the mere possibility of an estate squabble may cause clients stress and anxiety during the estate-planning process and cause them to put it off for that reason alone.

Why do people fight over inheritances? According to elder law attorney P. Mark Accettura, there are five basic reasons:

• Humans are predisposed to competition and conflict;

• Our psychological self is intertwined with the approval that receiving an inheritance confers;

• Humans are genetically predisposed toward looking for exclusions;

• The death of a loved one is mortality salience that triggers the accompanying death anxiety in humans; and

• The possibility of existence of a personality disorder that causes family members to distort and escalate natural family rivalries into personal and legal battles.28

While I agree with much of Accettura’s theory, he’s of the opinion that estate planning properly done through intergenerational communication for the right reasons can significantly reduce the proclivity to quarrel over inheritance. In fact, I believe that estate planning properly done can enhance a family’s emotional well-being. Furthermore, estate planning poorly done without communication between the givers and receivers can exacerbate and worsen inheritance fights.

Another reason for reticence about estate planning is a concern that too much wealth given to their loved ones will blunt their self-esteem and personal drive.29 There’s ample evidence of this in some wealthy families.

Tools for Use

There are a number of tools that planners can use to assist clients/donors psychologically with respect to finishing their planning, including: reflective listening, AI and MI.

Guiding Principles of MI

MI was developed in the 1980s primarily to assist patients who had chemical dependency problems. It’s a simple and elegant system whereby the client, who wants to change at some level, finds the reasons to change within himself, with the therapist merely acting as a guide. MI is based on four guiding principles:

• Resist the righting reflex (discussed below);

• Understand and explore the patient’s own motivations;

• Listen with empathy; and

• Empower the patient, encouraging hope and optimism.

It has application to estate/charitable planning, where clients/donors often are ambivalent about doing their planning. By asking the right questions, we can guide the client/donor to the conclusion that he needs to get his estate/charitable planning done and reassure him that we’re the right people to guide him through this process.

MI is based on the assumption that the righting reflex (that reflex that causes people to tell someone else when they’re on the wrong track), which humans have and helping professsionals have often to a greater degree, is counterproductive as it encourages the other person to take up the opposing side of the argument. Advisors tend to go to this righting reflex quickly because we assume that clients want our help and opinion immediately. However, this often isn’t true.

MI is based on four processes:30

• Engaging (establishing a helpful connection and working relationship);

• Focusing (developing and maintaining a specific direction in a conversation about change in behavior);

• Evoking (eliciting the client’s own motivations for change, which lie at the heart of motivational interviewing); and

• Planning (developing a commitment to change and a concrete plan of action).

MI isn’t a hoax in which the therapist tricks the patient into taking a course of action. There’s a spirit to it, as discussed below. MI isn’t done to or on someone; MI is done with someone. The professional using MI is a privileged witness to change, which the client usually figures out on his own.

The spirit of MI is based on the following four components:31

• Collaborative partnership. Among patient/client/donor and helping professional, particularly when behavior change is needed.

• Acceptance. It’s axiomatic that the practitioner unconditionally accepts the person just as he is at present.

• Evocative. MI seeks to evoke from the patient/client/donor that which he already has: his own motivation and resources for change, connecting behavior change with his own values and concerns.

• Honoring autonomy. MI requires a certain amount of detachment from outcomes, because the patient/client/donor can make up his own mind and is free to go in any direction, even one not advised.

Communication styles. There are essentially three communication styles that form a continuum of communication,32 and these can be used in the same conversation:

• Direct. Telling what to do.

• Follow. Listening.

• Guide. Middle ground, involving both.

MI spends most of its time in Guide mode, whereas most helping professionals use a follow-direct pattern, which often isn’t optimal and, at worst, self-defeating.

Core communication skills. They are: asking, listening and informing.33 Too many helping professionals spend too much time in the inform or ask/inform skillsets and not enough time listening. In my experience, as much as one quarter to one third of my estate-planning clients weren’t yet ready to do some estate planning even though they were in the office, ostensibly to do just that. They often simply wanted some non-judgmental professional listening. If your clients are similar to mine, you’ll miss the boat entirely at least a quarter of the time if you take estate-planning clients literally at their initial impression of wanting to do some estate planning.

Skills needed for MI. They include:34

• Asking open-ended questions.

• Affirming the other person.

• Reflective listening—this is very important.

• Summarizing.

• Informing and advising.

Many estate planners proceed too quickly from asking questions, most of which are closed-end in the form of yes/no and multiple choice. This line of questioning results in leading the client to the desired answer and then immediately informing and advising. If they’re not being listened to, clients may decide to change professionals.

Roadblocks to active listening. In 1970, Dr. Thomas Gordon set out 12 of what he calls “roadblocks” to effective listening, which are responses by individuals that don’t constitute what he calls “active listening”:35

• Ordering, directing or commanding.

• Warning, cautioning or threatening.

• Giving advice, making suggestions or providing solutions.

• Persuading with logic, arguing or lecturing.

• Telling people what they should do; moralizing.

• Reassuring, sympathizing or consoling.

• Questioning or probing.

• Withdrawing, distracting, humoring or changing the subject.

• Disagreeing, judging, criticizing or blaming.

• Agreeing, approving or praising.

• Shaming, ridiculing or labeling.

• Interpreting or analyzing.

These roadblocks to active listening can end a conversation prematurely. Not only does the purposeful estate planner or other professional helper have to suspend his own needs but also the helping professional has to avoid the “expert trap” in which asking questions one after another signifies control over the conversation. This pattern may lead to an assumption, often wrong, that once the helping professional has all of the answers to the questions, there will be a solution, which, again, often isn’t true. This heightened expectation is a trap for an expert.36 The roadblocks to active listening also are examples of the righting reflex at work, because helping professionals are predisposed to and programmed to ask and respond, quite often violating one of these roadblocks.

Reflective listening. The concept of reflective listening is easy to understand; its application to real life conversations can be difficult because of our tendency to go down the road of one or more of the 12 roadblocks set forth above, which involves the righting reflex. You simply mirror back and summarize for the client what the client just said. This is more than a mere echo; it demonstrates that you’re paying attention and can give the client a feeling that you understand him and what he’s going through.

Ambivalence. People who are thinking about making a change in their lives are ambivalent: Part of them wants to change, and part of them wants to maintain the status quo. By gently guiding clients in conversation, the planner has the clients convince themselves that the change is in their best interests. If you listen to ambivalent people discuss making that change, they’ll often engage in change talk (when they’re in favor of change—for example, completing their planning) and sustain talk (when they’re in favor of maintaining the status quo—for example, doing nothing) during the same conversation.

Planners can use the principles of MI to guide clients/donors toward closure in the estate/charitable planning process. Most clients/donors are ambivalent about doing their estate/charitable planning and engage in both change talk and behavior and sustain talk and behavior. By properly responding to the sustain talk and encouraging the change talk, the planner can play a role in assisting clients/donors to get them the therapeutic benefits of finishing their estate/charitable planning.

AI

The second tool that’s available to estate planners is AI. AI represents the intersection of the words “appreciate” and “inquire.” It’s both a philosophy and a methodology for positive change.37 The proponents of AI, which was conceived in the early 1980s by David L. Cooperrider, then a Ph.D. student at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, believe that far more progress can be made by a focus on the positive attributes of the system than on a focus on the negatives, weaknesses or shortcomings of the system because there’s less resistance to enhancing what’s done well, even if it means phasing out or changing some weak areas.38

Basis and theory underlying AI. AI is based on the theory of social constructionism, which posits that an individual’s notion of what’s real, including his sense of his problems, is constructed in daily life through communications with others and is subjective and able to be changed.39 There are things that a person or organization does very well—what gives life to the person or system, and the focus is on those positives with a view toward taking one to positive changes. Contrast this with the change management or problem-solving systems, which identify problem areas and strive to solve them, ignoring that which is working well.

In addition to the social constructionist principle, AI is based on the following four principles:40

• Simultaneity principle. Inquiry creates change and should occur simultaneously.

• Poetic principle. We can choose what we study. People have the power to choose positivity.

• Anticipatory principle. Images inspire and guide future action.

• Positive principle. Positive questions lead to positive change.

AI involves the art and practice of asking questions that strengthen a system’s capacity to understand, anticipate and heighten positive potential.

How can AI be used in estate/charitable planning? The possibilities are endless. For starters, family businesses that need succession planning can avail themselves of AI.41 Planners can use AI with donors who are unclear about how they want their gifts used.

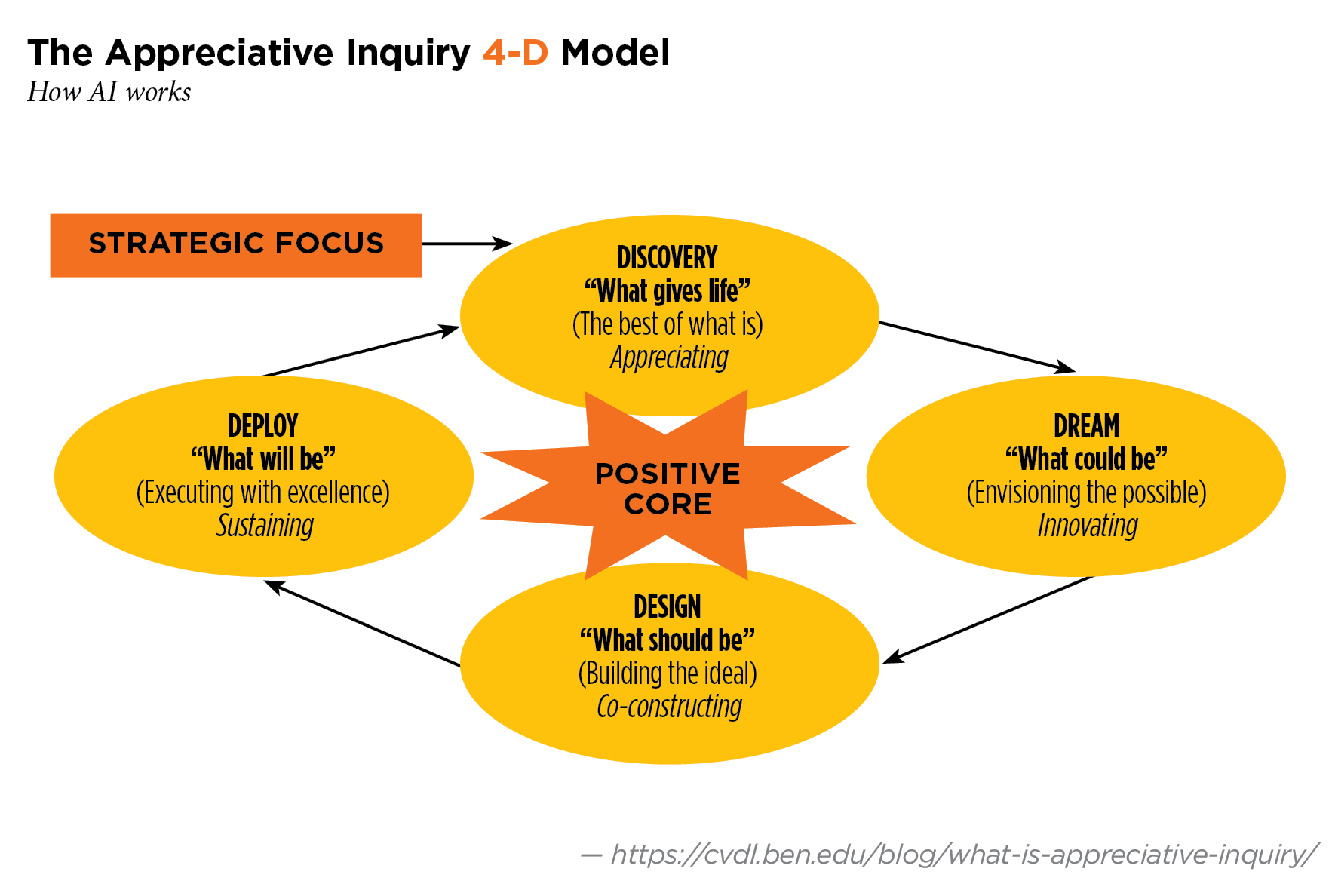

“The Appreciative Inquiry 4-D Model,” p. 61, explains the process of AI pictorially:42

The desired outcome of Discovery is appreciating the best of what is;

The desired outcome of Dream is imagining/envisioning what could be;

The desired outcome of Design is innovating/co-constructing/discovering what should be; and

The desired outcome of Deploy is delivering/creating/sustaining what will be.

Endnotes

1. L. Paul Hood, Jr.,“Back to the School of Hard Knocks: Thoughts on the Initial Estate Planning Interview-Revisited,” Wealth Strategies Journal (March 26, 2014) (“Hard Knocks”). See also L. Paul Hood, Jr., “From the School of Hard Knocks: Thoughts on the Initial Estate Planning Interview,” 27 ACTEC Journal 297 (2002).

2. Robert W. Firestone and Joyce Catlett, Beyond Death Anxiety (Springer Publishing Company 2009), at p. 16.

3. Sheldon Solomon, Jeff Greenberg and Tom Pyszczynski, The Worm at the Core: On the Role of Death in Life (Random House 2015), at pp. 26-28.

4. See, e.g., James C. Diggory and Doreen Z. Rothman, “Values Destroyed By Death,” 63 Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, No. 1, at pp. 205-210 (1961).

5. Russell N. James, III, Inside the Mind of the Bequest Donor (self-published 2013), Chapters 4 and 5.

6. Ibid., at p. 31.

7. Ibid., at p. 54.

8. Ibid., at p. 57.

9. Ibid., at p. 46.

10. Eleven of these were discussed in L. Paul Hood, Jr. and Emily Bouchard, Estate Planning for the Blended Family (Self-Counsel Press 2012). Recently, Hood added the fear of probate.

11. See, e.g., Mark Glover, “A Therapeutic Jurisprudential Framework of Estate Planning,” 35 Seattle University Law Review 427 (2012).

12. On being assured that his testamentary wishes are in order after he signed his will, Ishmael describes his satisfaction: “After the ceremony was concluded upon the present occasion, I felt all the easier; a stone was rolled away from my heart.” Herman Melville, Moby-Dick; or The Whale (Penguin Books 2003) (1851), at p. 249. See also Thomas L. Shaffer, Death Property and Lawyers (Dunellen 1970), at p. 77.

13. See, e.g., Nathan Roth, The Psychiatry of Writing a Will (Charles C. Thomas 1989), at pp. 44, 46 and 48.

14. Cognitive distortions have been explained as “ways that our mind convinces us of something that isn’t really true. These inaccurate thoughts are usually used to reinforce negative thinking or emotions—telling ourselves things that sound rational and accurate, but really only serve to keep us feeling bad about ourselves.” See, e.g., John M. Grohol, “15 Common Cognitive Distortions,” http://psychcentral.com/lib/15-common-cognitive-distortions/0002153.

15. Roth, supra note 13, at p. 46.

16. Glover, supra note 11, at p. 437.

17. Ibid., at p. 437.

18. See, e.g., Mario Mikulincer, Victor Florian and Gilad Hirschberger, Gilad (2003). “The existential function of close relationships. Introducing death into the science of love,” Personality and Social Psychology Review 7 (1): 20-40.

19. See, e.g., James, supra note 5, Chapter 5.

20. Abram Rosenblatt, Jeff Greenberg, Sheldon Solomon, Tom Pyszczynski and Deborah Lyon, “Evidence for Terror Management Theory: The Effects of Mortality Salience on Reactions of Those Who Violate or Uphold Cultural Values,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol 57(4) (October 1989), at pp. 681-690.

21. See, e.g., Ernest Becker, The Denial of Death (Free Press Simon & Schuster 1973).

22. Chris R. Fraley, “A Brief Overview of Adult Attachment Theory and Research,” https://internal.psychology.illinois.edu/~rcfraley/attachment.htm.

23. I recall an unfortunate case that went to the state court of appeal twice over family portraits that could have been duplicated.

24. Edwin S. Schneidman, Death: Current Perspectives (Jason Aronson 1976); Edwin S. Schneidman, Deaths of Man (Quadrangle/New York Times Book Co. 1973), Chapter 4.

25. Jean-Paul Sartre, Being and Nothingness (1943).

26. Shaffer, supra note 12, at pp. 81-82. See also James, supra note 5.

27. www.caring.com/articles/wills-survey-2017.

28. Mark P. Accettura, Blood & Money: Why Families Fight Over Inheritance and What To Do About It (Collinwood Press, LLC 2011).

29. Warren Buffett, in an article in Fortune magazine (Sept. 29, 1986), is quoted as saying the optimal amount of inheritance to leave children is “enough money so that they would feel they could do anything, but not so much that they could do nothing.”

30. William R. Miller and Stephen Rollnick, Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change (3rd ed). (The Guildford Press 2013) (Motivational Interviewing), Chapter 3.

31. Ibid., at pp. 14-24.

32. Ibid., at pp. 4-5.

33. Ibid., at, pp. 4-5.

34. Ibid., Chapter 6.

35. See, e.g., www.gordonmodel.com/work-roadblocks.php.

36. Motivational Interviewing, supra note 30, at p. 42.

37. Natalie May, Daniel Becker, Richard Frankel, Julie Haizlip, Rebecca Harmon, Margaret Plews-Ogan, John Shorling, Annie Williams and Diana Whitney, Appreciative Inquiry in Healthcare: Positive Questions to Bring Out the Best (Crown Custom Publishing 2011), at p. 3.

38. David L. Cooperrider, Diana Whitney and Jacqueline M. Stavros; Appreciative Inquiry Handbook For Leaders of Change 2nd Ed. (Crown Custom Publishing 2008), at p. xv (Handbook).

39. Ibid., at pp. 14-15.

40. Ibid., at pp. 8-10.

41. Dawn Cooperrider Dole, Jen Hetzel Silbert, Ada Joe Mann and Diana Whitney, Positive Family Dynamics (Taos Institute Publications 2008).

42. https://cvdl.ben.edu/blog/what-is-appreciative-inquiry/. There are many different ways that the 4-D Cycle is illustrated and described. Handbook, supra note 38, at pp. 5 and 34. Some newer descriptions employ a 5-D model, in which the first “D” is Definition of the presenting opportunity. See, e.g., https://appreciativeinquiry.champlain.edu/learn/appreciative-inquiry-introduction/5-d-cycle-appreciative-inquiry/.