Popularity among index-based mutual funds and exchange-traded funds (ETFs) in recent years is partly attributable to the fact that many actively managed mutual funds have had difficulty consistently outperforming the market, especially when costs are factored in. The first ETF was launched in 1993, and at the end of 2012 there were more than 1,300 ETFs in the market, with nearly $1.4 trillion in assets under management. Along with the growth of ETFs has come increased innovation in ETF and mutual fund strategies – and among the most notable has been the evolution of fundamentally weighted strategies.

ETFs were originally designed to mimic the most popular indexes such as the S&P 500®, Russell 1000®, and MSCI EAFE. These indexes are market-cap weighted, meaning the company with the largest market capitalization has the largest weight in the index. As a result, they tend to overweight overvalued stocks and underweight undervalued stocks.

Fundamental strategies are sometimes referred to as alternative beta, strategy beta, or smart beta, given they provide broad-based market exposure (beta) and weight securities based on fundamental factors. Rather than providing the biggest weights to the largest companies, fundamental strategies weight securities based on factors such as sales, cash flow, and dividends. The fundamental strategies available in the market vary based on the factors they screen.

The Schwab Center for Financial Research® believes fundamental strategies can capture positive attributes of both traditional passive strategies and actively managed mutual funds. Their unique construction process may provide investment opportunities different from those of market-cap-weighted strategies.

Fundamentally weighted indexes

Rob Arnott and his colleagues at Research Affiliates pioneered the use of the Fundamental Index® Methodology. Based on their research, Research Affiliates has shown that there is value in breaking the link between price and portfolio weight, and instead, weighting by fundamental measures of company size.

Fundamental strategies represent an evolutionary step in indexing, moving beyond traditional market-cap indexing by applying logic and intelligence to index construction. Fundamental strategies screen securities in a fashion similar to many actively managed mutual funds and ETFs. However, by following a rules-based discipline and rebalancing at predetermined intervals, fundamentally weighted indexing removes the emotion that often hurts active managers. On the other hand, traditional market-cap strategies adjust portfolio weights only when securities are added or deleted from the underlying index.

Market-cap vehicles are designed to provide cost effective exposure to broad market indexes. Since actively managed mutual funds have had difficulty consistently outperforming passive benchmarks over time, market-cap mutual funds and ETFs have generally been embraced by investors as cheap beta. Rather than paying higher fees for actively managed funds, investors can control costs more efficiently with market-cap strategies.

Fundamental strategies, available in both indexed mutual funds and ETFs, can also provide cost-effective and tax-efficient exposure to the markets. Because fundamental indexes screen and weight securities based on economic factors, they may have a value tilt, but they are not value indexes. Fundamental indexes tend to include value, core, and growth securities.

With fundamental strategies, investors have more options for investing in market segments. They can select from traditional market-cap, actively managed, and fundamental strategies. Investors need to understand the differences in strategies and the types of environments in which they tend to outperform and underperform when making investment decisions.

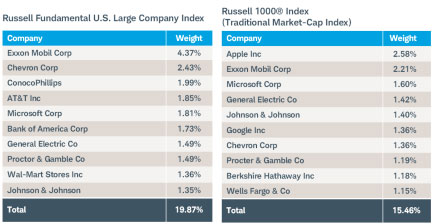

Same initial pool of stocks

While market-cap indexes and fundamentally weighted indexes may begin with the same basket of eligible securities, differences in construction can lead to dramatically different results. For example, Exhibit 1 shows the top 10 holdings in the Russell 1000 Index and the Russell Fundamental U.S. Large Company Index. While several companies are the same, the weights are different. Apple is the largest company in the Russell 1000 Index because it’s the largest company by market capitalization. Conversely, Apple isn’t even represented in the top 10 holdings of the Russell Fundamental U.S. Large Company Index; as of September 30, 2013, Apple was the 44th-largest holding in the Russell Fundamental U.S. Large Company Index.

Exhibit 1: Comparison of the Top 10 Holdings of a Fundamental and Market-Cap Index

Source: Russell Investments. Data as of September 30, 2013. Holdings are subject to change without notice. For illustrative purposes only. There is no guarantee that companies listed were or will be profitable in the future.

Because of the construction methodology, the larger-cap bias of market-cap indexes means they’re likely to outperform when the biggest companies are outperforming the overall market. Fundamentally weighted indexes tend to outperform in value cycles and markets in which there is a broadening of leadership – meaning less dependence on the biggest companies.

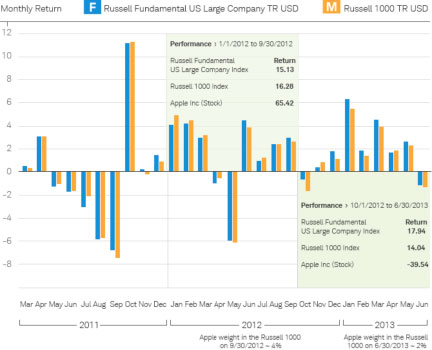

To illustrate this point, let’s focus once again on Apple. Apple was the darling of Wall Street, ultimately becoming the largest company by market capitalization in the United States. As Exhibit 2 reflects, through the first three quarters of 2012, Apple was up 65.42% and was the largest company in the Russell 1000 Index (~4%). Due in part to Apple’s extraordinary performance and large weight in the index, the Russell 1000 Index outperformed the Russell Fundamental U.S. Large Company Index (16.28% vs. 15.13%) over this time period. Most fundamentally weighted indexes and many active managers underweighted Apple, so when Apple outperformed the overall market, it provided an advantage to market-cap indexes.

Then, Apple fell 39.54% from the end of the third quarter 2012 to the end of the second quarter 2013. During this period, the Russell Fundamental U.S. Large Company Index outperformed the Russell 1000 Index (17.94% vs. 14.04%). The “Apple effect” helped the market-cap index when Apple was rising, but hurt the market-cap index when it was falling due to its large weighting in the index.

Exhibit 2: Apple Effect

Source: Morningstar Direct. Data as of March 1, 2011 to June 30, 2013. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

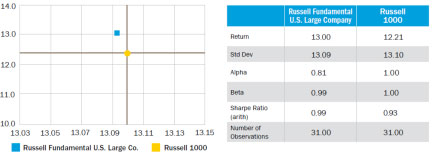

As demonstrated by the Apple effect, the Russell Fundamental U.S. Large Company Index and the Russell 1000 Index experience different results over time. These differences are largely attributable to the ways the indexes are constructed. While Exhibit 3 shows how the Russell Fundamental U.S. Large Company Index has delivered excess returns (13.00% versus 12.21%) with similar amounts of risk (13.09% versus 13.10%) compared to the Russell 1000 since inception (2/24/11), there are environments in which market-cap strategies will generate better results (see Exhibit 2). Therefore, we believe that there is merit to combining market-cap and fundamental strategies when building portfolios.

Exhibit 3: Risk/Return 3/1/2011-9/30/2013

Source: Morningstar Direct. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

Why fundamental?

While market-cap ETFs can provide cost-effective exposure to virtually every segment of the market, investors need to understand how they are constructed and the biases introduced through their methodology. Fundamentally weighted indexes begin with the same basket of securities as market-cap indexes, but weight securities based on fundamental factors such as sales, cash flow, and dividends. The weightings and corresponding results can be substantially different.

Our research shows that fundamental strategies have delivered attractive risk-adjusted results relative to market-cap strategies over their limited existence. Based on our research, we believe fundamental strategies can be an important complement to both market-cap and active strategies.

Anthony Davidow is responsible for providing Schwab’s point of view on asset allocation and portfolio construction. He is also responsible for providing research and analysis on alternative beta strategies and how investors should incorporate them in their portfolios.

For additional insights on fundamental strategies, please visit http://www.schwab.com/public/schwab/resource_center/fundamentally_weighted_indexes.html.

Glossary of Terms

Beta. A measure of the volatility, or systematic risk, of a security or a portfolio in comparison to the market as a whole. Beta is used in the capital asset pricing model (CAPM), a model that calculates the expected return of an asset based on its beta and expected market returns.

Fundamentally weighted. A type of equity index in which components are chosen based on fundamental criteria as opposed to market capitalization. Fundamentally-weighted indexes may be based on fundamental metrics such as adjusted sales, operating cash flow, and dividends + buybacks. Proponents of these indexes claim that they are a more accurate aggregate measure of the market because market capitalization figures tend to overweight companies that are richly valued while underweighting companies with low valuations. Fundamental indexes are sometimes referred to as alternative beta or smart beta.

Market-cap weighted. Most of the broadly-used market indexes today are "cap-weighted" indexes, such as the S&P 500, Russell, and MSCI indexes. In a cap-weighted index, large price moves in the largest components can have a dramatic effect on the value of the index. Some investors feel that this overweighting toward the larger companies gives a distorted view of the market.

MSCI EAFE Index. The MSCI EAFE Index is recognized as the pre-eminent benchmark in the United States to measure international equity performance. It comprises the MSCI country indices that represent developed markets outside of North America: Europe, Australasia and the Far East.

Russell 1000 Index. The Russell 1000 Index measures the performance of the large-cap segment of the U.S. equity universe. It is a subset of the Russell 3000® Index and includes approximately 1000 of the largest securities based on a combination of their market cap and current index membership. The Russell 1000 represents approximately 92% of the U.S. market.

Russell Fundamental U.S. Large Company Index. The Russell Fundamental U.S. Large Company Index measures the performance of the large company size segment by fundamental scores. The fundamental overall company scores are created using as the universe the members of the Russell 3000® Index.

S&P 500® Index. The S&P 500 Index has been widely regarded as the benchmark of the large cap U.S. equities market since the index was first published in 1957. The index includes 500 leading companies in leading industries of the U.S. economy based on market-capitalization, capturing 75% coverage of U.S. equities.

Important Disclosures

Investors should consider carefully information contained in the prospectus, including investment objectives, risks, charges, and expenses. You can request a prospectus by calling Schwab at 800-435-4000. Please read the prospectus carefully before investing.

Investment returns will fluctuate and are subject to market volatility, so that an investor’s shares, when redeemed or sold, may be worth more or less than their original cost. Unlike mutual funds, shares of ETFs are not individually redeemable directly with the ETF. Shares are bought and sold at market price, which may be higher or lower than the net asset value (NAV).

The information provided here is for general informational purposes only and should not be considered an individualized recommendation or personalized investment advice. The investment strategies mentioned here may not be suitable for everyone. Each investor needs to review an investment strategy for his or her own particular situation before making any investment decision.

This information is not intended to be a substitute for specific individualized tax, legal or investment planning advice. Where specific advice is necessary or appropriate, Schwab recommends consultation with a qualified tax advisor, CPA, Financial Planner or Investment Manager.

Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Indexes are unmanaged, do not incur management fees, costs and expenses, and cannot be invested in directly.

Russell Investments and Research Affiliates LLC have entered into a strategic alliance with respect to the Russell Fundamental Indexes. Subject to Research Affiliates’ intellectual property rights in certain content, Russell Investments is the owner of all copyrights related to the Russell Fundamental Indexes. Russell Investments and Research Affiliates jointly own all trademark and service mark rights in and to the Russell Fundamental Indexes.

The Schwab Center for Financial Research is a division of Charles Schwab & Co., Inc.

Russell Investments and Research Affiliates are not affiliated with Charles Schwab & Co., Inc.

©2013 Charles Schwab & Co., Inc. All rights reserved. Member SIPC.

(1113-8135)