There is a notion that I have a “bearish” undertone in my financial writings. Truth be told, I just don’t get excited about most equity markets (at current valuations) or many other available liquid investment choices. As we have shared in previous blogposts, central banks have materially changed the concept of free price formation and propelled financial markets to unprecedented levels. Not only should we question the significant disconnect between the financial and real economy, but we also must consider when the impact of overly accommodative policies will come “home to roost.” At this point, we are still living the dream of an extraordinary financial experiment, and it is for this reason that our focus has remained on thematic investing with a real-asset bias. To preserve purchasing power requires the right identification of—and allocation to—the next big themes.

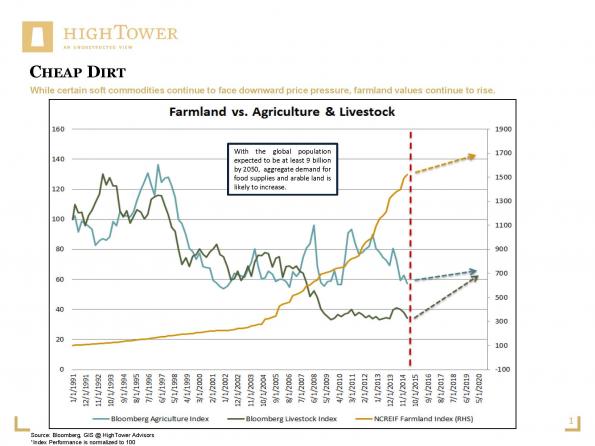

Looking back to Ferraris for the Farmers, one of our 2012 updates, we made the case for agricultural investing, including respective commodities, farmland, and even entire nations (e.g., Brazil) as proxies for the opportunity. In critical self-review, the outcome would have been mixed, with agricultural commodities having been under pressure but farmland still on a tear. Whereas critics are now calling for “the valuable dirt” to be the next investment bubble to pop because of the first significant price decline since 1986 (recently recorded in the Federal Reserve Bank district of Chicago, covering Illinois, Iowa, and other agricultural states), the long-term structural investment case continues to be compelling.

Estimates call for the world population to exceed 9 billion by the year 2050—an increase of 30 percent from current levels; securing food supplies, in this respect, is considered one of the major challenges of the 21st century. Global food production must increase by 70 percent in order to meet new demands, and this estimate does not even account for 1) the impact of climate change and (often related) soaring prices of agricultural goods as a result of natural disasters, droughts, etc., or 2) the fact that more than one billion people (!) currently go hungry every day.

Closing the anticipated output gap depends largely on the availability and utilization of arable land, the impact of weather and climate change, and the evolution of consumption patterns to higher-protein diets—three rather challenging factors, especially for most emerging market economies. Although the overall impact of expected changes and food-related hurdles differ by region, no part of the world will remain unaffected. It is estimated that, on a per capita basis, global arable land availability will decline steadily over the next few decades (from 0.218 hectares per person today to 0.181 hectares per person in 2050), and that crop yields must increase by up to 110 percent to meet the growing world population.

Regarding the oft-cited investment hysteria over farmland, the reality appears to be different: if a “stretched” demand vs. supply scenario were unfolding, I would be willing to accept the characterization of farmland as a “bubble.” However, of the $2.5 trillion worth of U.S. farmland, most is owned by farmers—with just $10 billion, or 0.4 percent, owned by investment funds. Nevertheless, for the “select” crowd that has opted to invest in farmland, returns have been attractive: According to the NCREIF Farmland Index (a measure of performance related to pools of individual agricultural properties acquired for investment purposes only), farmland has produced an average annual return of 12.1 percent between the years 1991 and 2015, compared to the S&P 500 return of 10.8 percent over the same timeframe.

The agricultural investment space still lacks structure, including professional advocates and measures of comparison (indices and consequent benchmarking), as well as a deep offering of adequate retail instruments—all characteristics that seem to imply “emerging” rather than “in a bubble.” Drawing on pragmatic experience, it is not too far-fetched to compare farmland to the infrastructure investment movement some years ago—well before this particular opportunity became a “household” allocation choice. Regardless, savvy investors already have access to “derivatives” of agricultural investing for strategically placing their bets, including single securities and select mutual funds/ETFs. Tactically, the underperformance of agricultural commodities has been anchored in unique conditions, most notably the decline in the price of energy; based on our arguments, this consolidation will also run its course, thus creating opportunities to focus on today.

Matthias Paul Kuhlmey is a Partner and Head of Global Investment Solutions (GIS) at HighTower Advisors. He serves as wealth manager to High Net Worth and Ultra-High Net Worth Individuals, Family Offices, and Institutions.