The market crisis of 2008 to 2009 was inescapable and bloody. Stock market investors saw their holdings evaporate. But at least they could stop the bleeding by selling their liquid securities. Meanwhile, investors in alternative assets, especially hedge funds and private equity or real estate limited partnerships, watched their investments crater — but found they couldn't access their capital at all.

Investors in these assets traditionally have been willing to give up liquidity, and have been willing to suffer the consequences if the market goes into a crisis, to achieve higher returns. They have bought the idea that, by investing in illiquid assets, they will earn an illiquidity premium, which will make it worth their while to temporarily give up access to their money. Most of these investors, along with their advisors, have taken this premise on faith. The question is: should they?

Does the Illiquidity Premium Really Exist?

In most asset classes, it's impossible to measure whether investors really are compensated for giving up liquidity. Many hedge funds and limited partnerships don't report their earnings. For the real estate asset class, though, there's a reasonably good way of comparing the returns from liquid and illiquid ways of investing.

Investors who value liquidity can invest in real estate through publicly traded real estate investment trusts (REITs) — companies whose stock is traded daily on the major stock exchanges, and whose earnings and returns are derived from the rents generated through their ownership and management of real estate. REITs are required to pass almost all of their taxable earnings along to investors — which means that REIT returns truly represent the real estate asset class, but without investors having to take on the illiquidity of buying and selling, say, shopping centers.

Meanwhile, real estate investors who are willing to give up liquidity can benchmark their results using measures such as the NCREIF Property Index (NPI), a widely used measure computed by the National Council of Real Estate Investment Fiduciaries, an organization of pension funds that invest in property, such as shopping centers. If the proponents of the “illiquidity premium” are right, then returns of “private equity” real estate (as measured, for example, by the NPI) should be greater than returns of “public” real estate (as measured, for example, by the FTSE NAREIT Equity REITs Index).

Three teams of academic economists have done just such a comparison to determine who's better at investing in real estate — REIT managers or private equity fund real estate investment managers. The comparison has to be done carefully, though, because the measures aren't exactly comparable.

First, the NPI is a measure of unlevered returns at the property level, while the FTSE NAREIT Index measures returns at the company level. That's an important distinction because the use of debt (leverage) increases the return on equity investments. Of course, pension funds generally use debt when they invest in real estate, but the effect of that debt is scrubbed away before the NPI is computed. REITs, too, use leverage to invest in real estate, but the effect of their debt isn't scrubbed away in computing the FTSE NAREIT Index's performance. To do the comparison, then, the academic researchers have to adjust REIT returns to eliminate the effect of leverage.

Another difference is that the NPI is restricted to core property types — office buildings, industrial/warehouse facilities, retail properties, rental apartments, and hotels — while REITs also invest in non-core (or “core-plus”) property types, such as timberlands, health care properties, self-storage facilities, and sophisticated data centers. To make a fair comparison, then, the academic researchers have to restrict their analysis to REITs that hold core property types.

Finally, REITs turn out to be a much less costly way for investors to access the real estate asset class. Pension funds typically pay about 50 basis points in fees and expenses for active investment in liquid REIT strategies, while the same pension funds pay about 115 basis points to managers who invest directly in illiquid real estate. (Individuals can access REIT index mutual funds for more like 25 basis points.)

Illiquidity Premium? More Like a Penalty

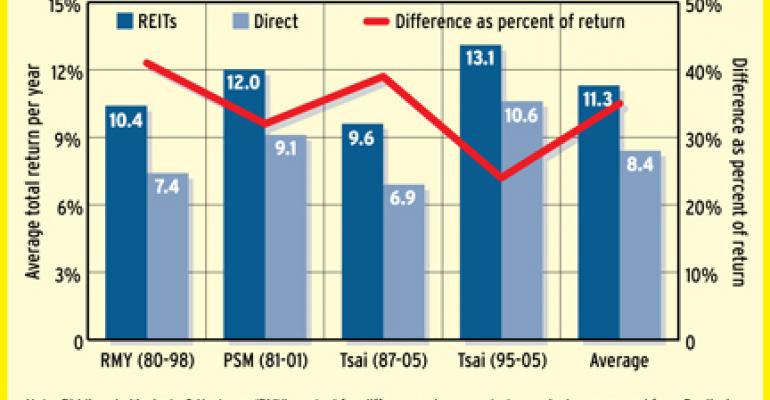

Timothy Riddiough, professor of real estate at the University of Wisconsin, found with two co-authors that long-term average annual returns on real estate, after adjusting for leverage, differences in property type, and fees, were about 10.44 percent per year for publicly traded REITs, compared to just 7.36 percent per year for non-REIT investment managers. (See table.) That means that REIT investors retained their liquidity and enjoyed returns roughly 42 percent greater than those real estate investors who gave up access to their money in search of an “illiquidity premium.”

Joseph Pagliari, professor of real estate at the University of Chicago's Booth School of Business, found with two co-authors that long-term average annual returns, after adjusting for leverage and property type, but not for differences in fees, were about 12.34 percent per year for publicly traded REITs, compared to just 9.34 percent per year for non-REIT investment managers. REIT investors, again, retained their liquidity and enjoyed returns roughly 32 percent greater than those real estate investors who gave up access to their money, even before considering the large differences in fees and expenses.

Finally, Patrick Tsai, a graduate student at MIT who probably accomplished the fairest comparison (because he was building on the earlier studies), found that publicly traded REITs provided returns roughly 21 percent higher than non-REIT investment managers (13.12 percent vs. 10.61 percent) during the 1995 to 2005 period, and by 35 percent (9.57 percent vs. 6.90 percent) during the longer 1987 to 2005 period.

According to NCREIF, during the long real estate market cycle from 1990 to 2008 the net total return on unlevered core property investments averaged 7.6 percent per year. Open-ended diversified core property funds generated net total returns averaging 7.7 percent per year. Value-added funds, which invest in riskier properties, and add to that risk by using leverage of around 55 percent, generated net total returns averaging 8.6 percent per year. Opportunistic funds, which take wild bets on the riskiest property investments, and multiply their risks with leverage in excess of 65 percent, generated net total returns averaging 12.1 percent per year.

During the same long real estate market cycle, publicly traded REITs — which invest in core or core-plus properties using leverage averaging only about 40 percent, generated net total returns averaging 13.4 percent per year. That means that REIT managers outperformed managers of illiquid, value-added real estate funds by 56 percent, and opportunistic funds by 11 percent, even while taking less risk with their investors' capital.

In the real estate asset class, the lesson is clear: There is no illiquidity premium. What private equity actually delivers is dramatically lower returns, for the “privilege” of giving up liquidity.

Brad Case is vice president, Research and Industry Information at the National Association of Real Estate Investment Trusts