How much investing jargon do you need to master while saving for retirement?

The word “fiduciary” is a good example. A Financial Engines survey released Thursday finds that only 18 percent of Americans are sure what the word means. That kind of ignorance can be expensive: U.S. financial advisers are divided between “fiduciaries” required to put your interests first (like a doctor or lawyer), and others like brokers, more akin to salespeople, required only to push “suitable” products that may profit them more than you.

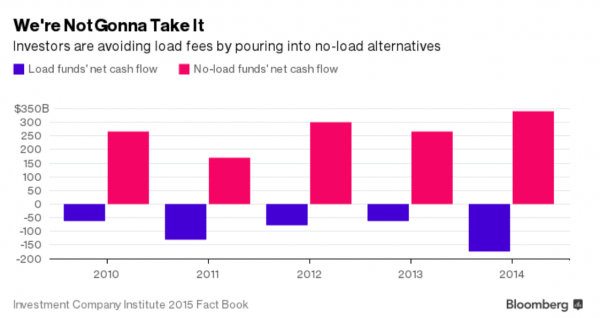

Judy McChester-Nedd, a 59-year-old retired executive in Helena, Ala., didn’t know the difference when she hired an adviser unconstrained by fiduciary duty. She says she asked for a conservative strategy and ended up losing 14 percent last year in actively managed mutual funds. Ian MacGregor, 38, is a consultant in Dublin, Ohio, who also didn’t know the difference. His adviser kept steering him into mutual funds with upfront load fees of as much as 5 percent. (There's another nugget of jargon you should know: A load is a one-time charge to invest in a fund. In other words, front-end load funds are investments where you lose money the moment you buy them.)

Nonfiduciary advisers are free to recommend only the products that earn them the highest commissions, which can come from both load fees and annual fees. Because they get paid in so many complicated ways, it can be hard to tell how much they're making off you and what their incentives are. Fiduciary advisers tend to get paid in more transparent ways, often by charging an annual fee based on the assets they manage.

Of course, not all nonfiduciary advisers charge high fees or push lousy bets, and fiduciary advisers aren't all perfect. But it’s hard to invest when you’re not sure whom to trust.

“I’ve lost confidence,” McChester-Nedd says. “The government needs greater oversight over this because regular people are getting hurt.”

MacGregor agrees: “There’s got to be some way to protect the less-savvy investor from being taken for a ride.”

Well, they may get their wish. Despite years of resistance from Wall Street, the U.S. Department of Labor is expected to announce soon the final version of a rule that may force financial advisers to abandon the way they’ve done business for decades. For the first time, all advisers may need to act as fiduciaries, putting their clients’ interests first when handling retirement accounts.

The rule could clear up some confusion. According to the survey of more than 1,000 people paid for by Financial Engines (a fiduciary advisory firm), 46 percent of Americans incorrectly believe that advisers already “are legally required to put the best interests of their clients first” when dealing with retirement assets.

The majority of respondents, 54 percent, knew advisers weren’t under that requirement, but they sure weren’t happy about it. Overall, 93 percent said it’s important that all advisers put clients’ interests first when providing retirement advice.

Wall Street counters that a strong fiduciary rule will make it less profitable to offer advice to lower- and middle-income Americans.

“This proposal, if enacted, would limit the ability of Americans to continue to receive personalized investment guidance for retirement plan accounts, which would result in a less secure retirement for many,” Kenneth Bentsen Jr., chief executive of the Securities Industry & Financial Markets Association, an industry group, wrote in one of more than 3,000 comments on the proposed “conflict of interest” rule last year.

Advocates of the rule say it may generate new insurance and investment business models that cost less and aren’t as likely to exploit the unsophisticated.

“The marketplace was changing anyway,” says Mitchell Caplan, CEO of Jefferson National, an insurance company which sells products to fiduciary advisers. He predicts that, in the future, technology will help fiduciary advisers serve more clients more efficiently. “There will be lots of companies and business models that continue to evolve,'' he says.

Much depends on how the final rule is implemented. In the initial proposal, firms handling retirement accounts needed to sign a contract with clients making clear they’d put their interests first. Figuring out what this means exactly may take a while, as courts could end up being the final arbiter of the rule’s language. It’s also not clear how the final rule would be enforced, though it might leave noncomplying firms open to penalties or lawsuits.

Whatever regulators and judges decide, many investors have already made a clear choice, as the number of investors willing to pay load fees has plunged:

MacGregor is among them, having switched his account to a fiduciary adviser charging him 0.5 percent per year. McChester-Nedd moved her money into cash and is still figuring out what to do with it. “This stuff is very complicated,” she says, adding she's “bewildered” by “inconsistent and inaccurate” information.

McChester-Nedd is confident, though, that she’ll figure it out eventually. Still, she worries about friends and family without her business background: “They’re totally at the mercy of the system.”