Target-date retirement funds have attracted a flood of money. With 401(k) savers relentlessly investing, the funds have grown from $71 billion in assets in 2005 to more than $500 billion today. Now that millions of investors are betting on the retirement portfolios, some analysts are asking a difficult question: Can the target funds actually provide enough income to last through long retirements? The fund companies think so, but some analysts are expressing doubts.

Most of the popular funds are too risky, said Ron Surz, president of Target Date Solutions, which designs target funds. The danger occurs because of the way the portfolios are structured, Surz said. The funds offer diversified portfolios designed to serve people who plan to retire in certain years, such as 2020 or 2040. Typical funds for young people start with 80 percent or more of their assets in equities and the rest in fixed income. As the savers age, the portfolios shift to more conservative allocations. By the retirement date, many funds have about 50 percent of assets in equities.

Surz said that the sizable equity stakes present too much risk for retirees. The hazards became clear in the downturn of 2008. For the year, the average fund with a maturity date of 2010 lost 22.5 percent, according to Morningstar. While the funds eventually recovered, some investors dumped their funds and did not wait for the rebound. “The target-date funds did serious harm to investors,” Surz said.

Surz agrees that young people should hold equities. But once a saver is within 10 years of retirement, the portfolio should gradually shift away from equities, Surz said. By the retirement date the portfolio should be entirely in Treasury bills and Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities. That way savers who must withdraw a big chunk of assets right away will not be at risk. After retirement, individual clients may elect different strategies. Some clients may prefer to hold fixed annuities that will provide guaranteed income. Cautious savers may elect to remain in cash.

With his extremely conservative approach, Surz represents a minority viewpoint. But many financial advisors share his opinion that target-date funds are flawed because they provide a one-size-fits-all approach. In many cases, individuals would be better served by customized solutions. Many wealthy retirees prefer big equity allocations, while other clients should hold mostly fixed income.

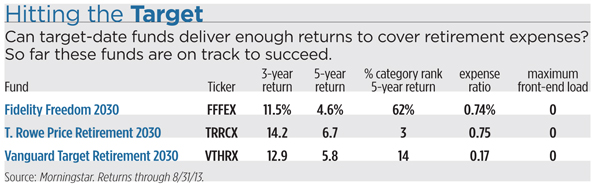

Advocates of target-date funds concede that customized approaches may be best, but they contend that the target funds are sound choices for do-it-yourself investors who might otherwise fail to diversify. The proponents note that the long-term performance of the funds has been decent. During the past 10 years, funds with maturity dates around 2030 have returned 5.8 percent annually.

In a recent report, Morningstar researchers concluded that the target funds seem likely to achieve their goals. The researchers considered a hypothetical 23-year-old worker who earns $45,000 and saves 7 percent annually. When the worker retires at 65, the target-date fund must cover 31 percent of living expenses. Using Monte Carlo simulations, Morningstar tested thousands of scenarios, including situations where stock returns were excellent or miserable. In 3 percent of the simulations, the saver exhausted assets by the time he reached 75. By 85, the failure rate reached 23 percent. At 95 the rate was 42 percent. Morningstar concluded that the odds were acceptable for most savers.

Morningstar tested the likely outcome for funds offered by major companies, including Fidelity, T. Rowe Price, and Vanguard. For all the funds, the odds of success seemed acceptable. One notable finding was that funds with more equities tended to have slightly higher success rates. T. Rowe Price, which has an above-average stake in equities, failed in 38 percent of scenarios by age 95. That was 2 percentage points better than Vanguard, which takes a more cautious approach.

But relatively aggressive funds clearly come with more risks in downturns. To appreciate the tradeoffs, compare T. Rowe Price Retirement 2010 (TRRAX)—which has 49 percent of assets in equities—with Vanguard Target Retirement 2010 (VTENX)—with 40 percent in equities. During the past five years, the T. Rowe Price fund outperformed, returning 6.0 percent annually, while the Vanguard fund returned 5.6 percent. But in the downturn of 2008, T. Rowe Price lost 26.7 percent, compared to 20.7 percent for Vanguard.

After the trauma of the financial crisis, some funds lowered their risk levels, but others took the opposite approach. Fidelity recently announced that it was raising the equity allocation in its target funds. Fidelity Freedom 2020 (FFFDX) is increasing its stock holdings from 53 percent of assets to 61 percent. Fidelity, which serves as record keeper for 12 million 401(k) savers, made the move after studying a variety of factors, including the market outlook and the behavior of plan participants. The calm reaction of clients in the financial crisis persuaded Fidelity that clients could tolerate more risk. During the downturn, few participants panicked and sold their shares. “The behavior was consistent through the periods of heightened volatility,” said Andrew Dierdorf, co-portfolio manager of the Fidelity Freedom funds.

Fidelity considered the outlook for stocks and bonds over the next 20 years. The researchers projected that stocks would return 6.5 percent annually after inflation, about equal to the long-term historical experience. Because bonds now have low yields, they are only likely to produce real annual returns of 1.5 percent, half the historical results, Fidelity figured. Since the outlook for fixed-income seemed so dismal, the researchers concluded that investors would need a bigger dose of equities to reach the goals.

Fidelity argues that investors who use its target-date funds can cover retirement expenses—provided shareholders save enough. Dierdorf said that 401(k) participants should save 10 percent to 15 percent of their incomes. But many participants are not saving nearly enough. For savers in their 20s, the median savings rate is currently 8 percent. Older participants save more. The median savings rate for people in their mid-60s is 13 percent. Dierdorf argues that for thoughtful savers, the target-date funds can provide a lifetime solution, enabling people to save enough during working years and then cover costs in retirement.