By Andrea Felsted

(Bloomberg Gadfly) --Ferrari wants to forget it’s a car and pretend it’s a handbag.

The maker of supercars would like to be seen as a luxury group -- to the consternation of some autos industry analysts. So, as Gadfly's luxury goods writer (who knows nothing about cars, I don't even own one), I thought I'd take a look. In many ways, the analogy stacks up. Sorry, petrol-heads.

A Ferrari is the ultimate luxury purchase. They're expensive, and very, very exclusive. There are long waiting lists to get your hands on one, and Ferrari can frustrate or satisfy demand as it sees fit. In other words, it’s a lot like an Hermes Birkin bag, lusted after by many, but deliberately kept in short supply.

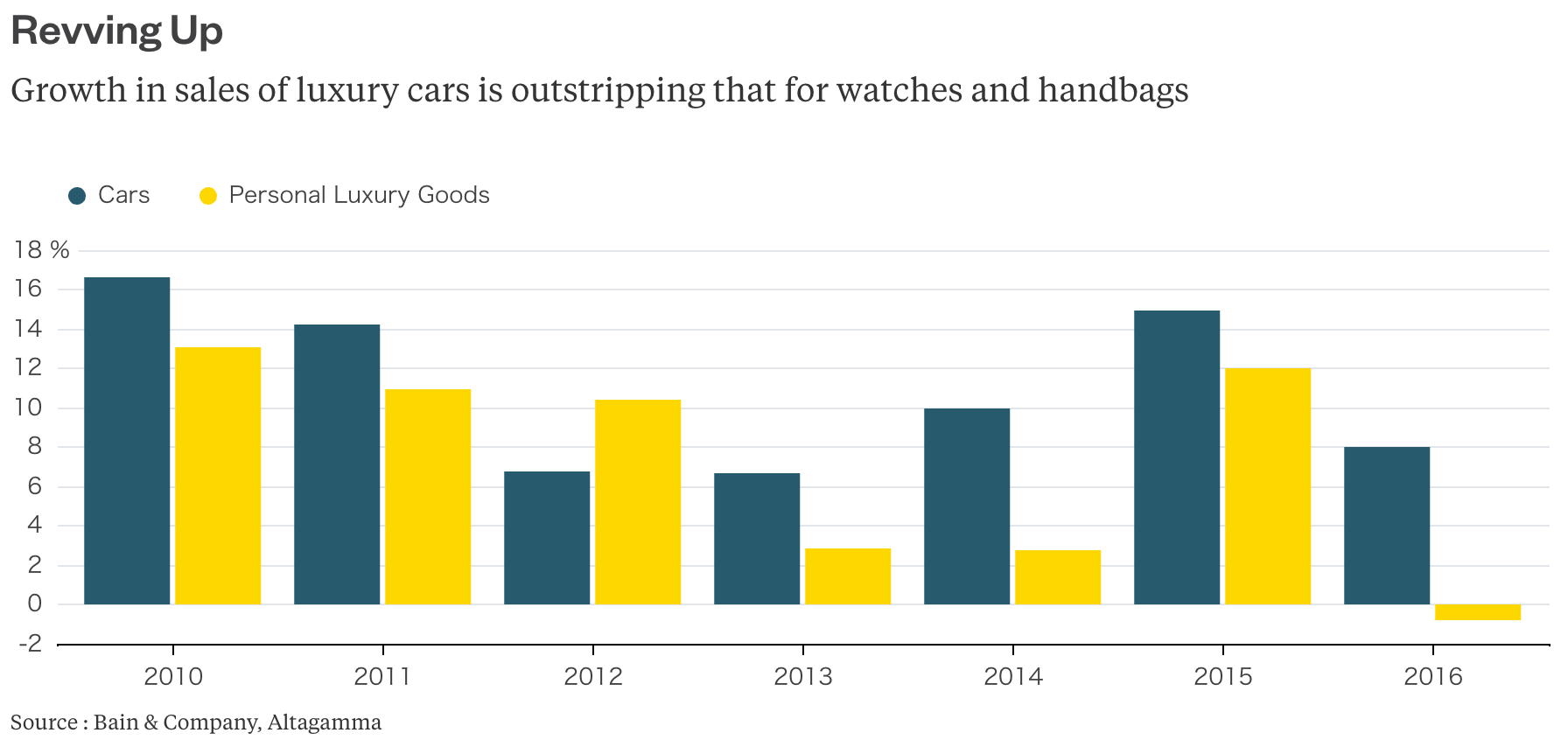

Luxury goods stocks are back in favor. Chinese growth is returning, while any tax cuts for rich Americans would be happy news for the people who sell expensive stuff. On that logic, Ferrari should benefit. It operates in a buoyant part of the market. Car sales outpaced all other categories of luxury spending in 2016, rising 8 percent, according to Bain & Company and Altagamma. Personal luxury goods fell 1 percent.

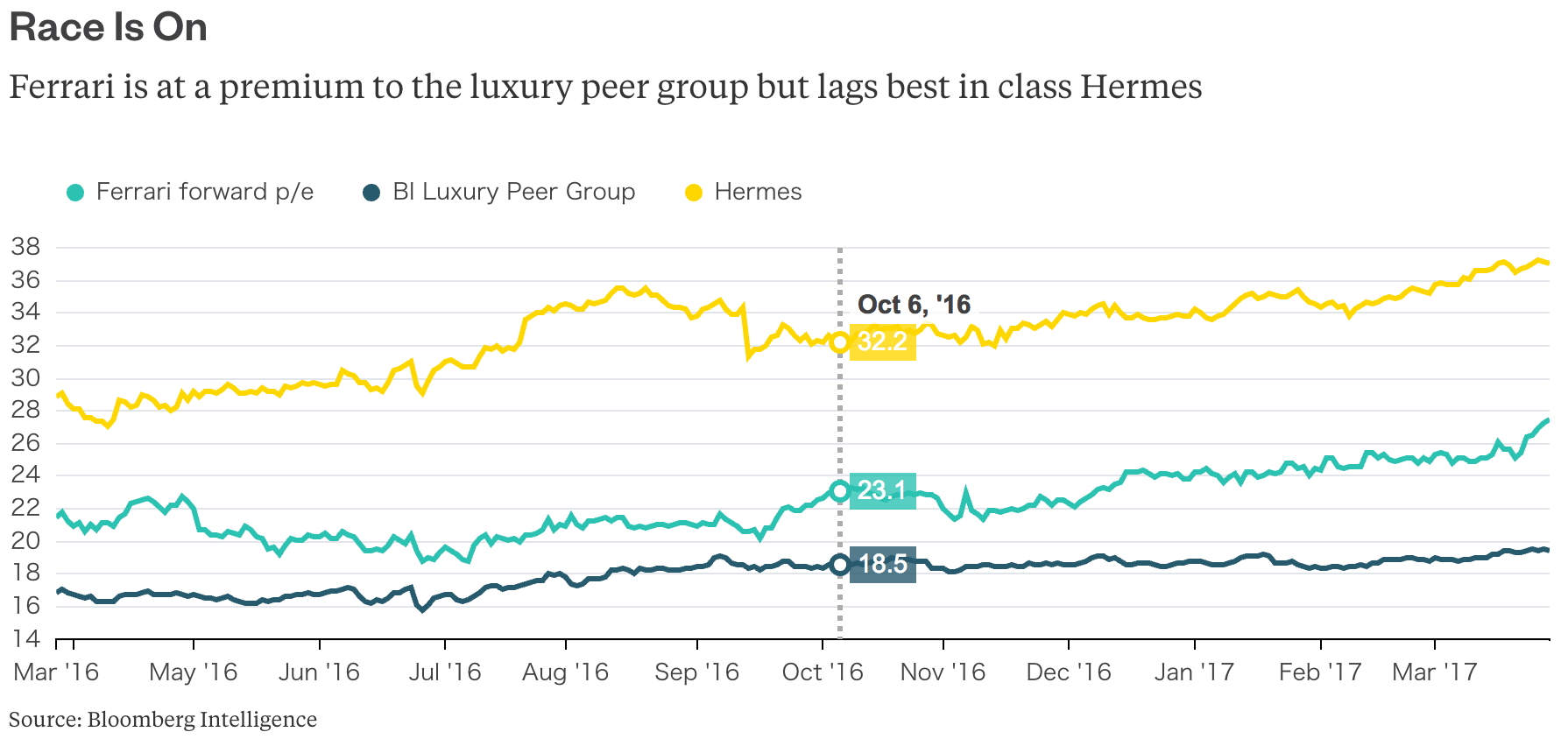

Still, even in the rarefied world of top-end consumption, Ferrari stock isn't cheap. The shares will cost you 27 times its expected earnings, much higher than the 19.5 times average for Bloomberg Intelligence's index of luxury companies.

Some premium may be justified. Cars are hot right now among the high-net worth crowd, while that "prancing horse" badge of exclusivity has value. Look at Hermes, whose forward price to earnings ratio is a mightily opulent 37 times.

Still, we mustn't get carried away. However hard Ferrari tries, it's still a carmaker. The shares of BMW AG and Daimler AG trade on about 8 times future earnings. I agree that Ferrari shouldn't be lumped in with the high-volume luxury carmakers, but there's something troubling about giddy talk from analysts about the shares hitting $100.

Like other manufacturers, Ferrari has to invest in plants and tooling. Plus there are the R&D costs to keep pace with new technology and emissions laws and to ensure its F1 team starts winning again. The company generated just 280 million euros ($302 million) in industrial free cash flow in 2016, having spent 340 million euros on capex: 11 percent of sales. Hermes's operational investments were 5 percent of sales.

Plus, as at Hermes, exclusivity will put a cap on growth. How can you broaden your appeal without losing the cachet that comes from rarity?

Exane BNP Paribas analysts say "category segregation" has been central to Hermes's success. This is where it keeps core leather goods expensive and out of reach, while selling more affordable silk scarves and costume jewelry to a bigger group of punters. Yet the Hermes strategy is looking shaky, Exane argues, as it introduces cheaper handbags.

Ferrari faces a similar dilemma. It could make more modestly priced SUVs -- although CEO Sergio Marchionne has played this down. The alternative is confining lower price points to other categories such as watches, clothing and accessories. Ferrari is trying this, but it hasn't taken off yet. Why pay 500 pounds for a Ferrari cashmere sweater, or 1,650 pounds for a suede jacket, when you could buy similar at Brunello Cucinelli SpA?

An alternative would be a shift into other high-end manufacturing, such as motorbikes or speedboats. Theme parks are another area of expansion, with one already operating in Abu Dhabi. These could be decent money-spinners, but tourist attractions hardly solve the exclusivity question nor explain all of the froth in the share price. Can you imagine an "Hermes World" on the Champs-Elysees?

Chris Bryant assisted with this column.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Andrea Felsted is a Bloomberg Gadfly columnist covering the consumer and retail industries. She previously worked at the Financial Times.

To contact the author of this story: Andrea Felsted in London at [email protected] To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Boxell at [email protected]