By Emily Barrett

(Bloomberg) --Perhaps the best that can be said of a painful year across financial markets is that there’s room for improvement in 2019. It’s less clear exactly what might pull investor sentiment, and Treasury yields, off the current lows.

Risk-averse trading in December -- which is on track to be the worst month for U.S. stocks since the 2008 crisis -- has dragged the benchmark 10-year Treasury yield down to 2.73 percent. That’s more than half a percentage point below its 2018 peak in October. Investors are responding in part to tightening financial conditions and a souring economic outlook, and some think that the Federal Reserve could be headed for a mistake with further interest-rate hikes.

Placating financial markets may not be on Fed Chairman Jerome Powell’s list of new year’s resolutions, but investors will be on alert when he joins his predecessors for an interview this Friday at the American Economic Association meeting. Jefferies LLC’s Thomas Simons doesn’t expect the Fed chief to suddenly start wringing his hands over the recent volatility in stocks. But another way to calm markets would be to note weak inflation, particularly if the Fed is leaning toward a pause in its rate-hike cycle.

“That could be an under-the-table signal that they were not going to be raising rates,” said Simons, a money-markets economist in New York, who expects the Fed to hold rates steady in the first quarter.

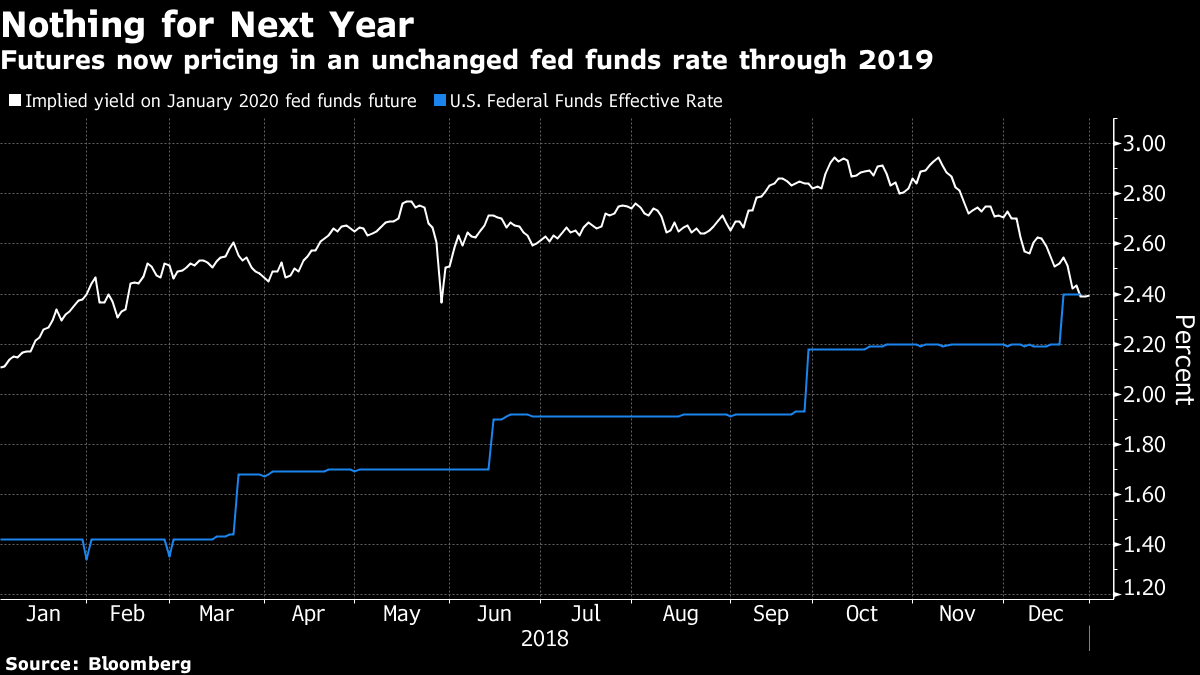

Such a signal could help patch up some differences between markets and the Fed, and even between rates traders. Volatile activity in futures ahead of December holidays wiped out the last vestiges of pricing for hikes next year, even though the Fed’s latest projections imply two increases in 2019. While this aggressive repricing has started to attract buyers of cheap eurodollar hedges for a March hike, swaps traders see the Fed’s next move as an interest rate cut in 2020.

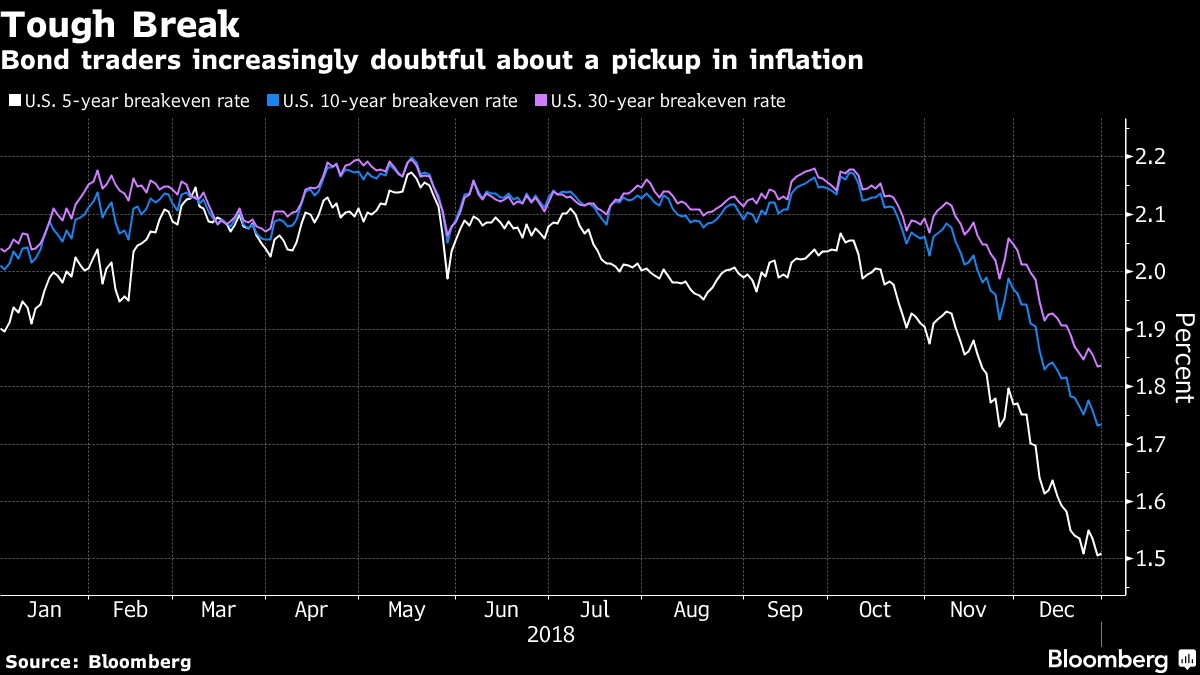

The corresponding decline in short-end Treasury rates has staved off an inversion in the yield curve -- which was very much on the market’s radar at the start of the month -- though long-end rates remain tethered by low inflation expectations. This is yet another point of disagreement between the market and the Fed, as the sliding trend in U.S. breakevens suggests traders see inflation remaining well below the central bank’s target of 2 percent for decades to come.

That said, it may still be too soon to call an end to the Fed’s hiking cycle. U.S. economic growth is tracking above trend and unemployment is at its lowest rate since the 1960s. This week’s crop of jobs data is widely expected to re-confirm that labor market strength, although the continuation of a trend that’s persisted for the better part of a decade is unlikely to lift investors’ spirits.

“The labor market data doesn’t have anything to prove on the upside, it really only has things to prove on the downside,” Simons said, noting that a softer report could support the case for the Fed to stop raising interest rates.

A more-conciliatory tone in Washington could also help repair investor sentiment, and senior administration officials have sought to reassure markets that U.S. President Donald Trump is not planning to fire the head of the Fed. But broader political dysfunction is unlikely to help. There is no sign at the moment of an accord to re-open the government after disagreements over the president’s demand for border-wall funding led to a partial shutdown. And with no fresh votes planned yet as the new Congress prepares to convene later this week, resolutions might be in short supply there too.

--With assistance from Edward Bolingbroke.To contact the reporter on this story: Emily Barrett in New York at [email protected] To contact the editors responsible for this story: Benjamin Purvis at [email protected] Elizabeth Stanton