By Liz Capo McCormick

(Bloomberg) --Don’t expect the U.S. Treasury market to go back to “normal” once the Federal Reserve starts reducing its crisis-era debt investments.

At least that’s the message from the likes of Credit Suisse, Goldman Sachs and Pimco.

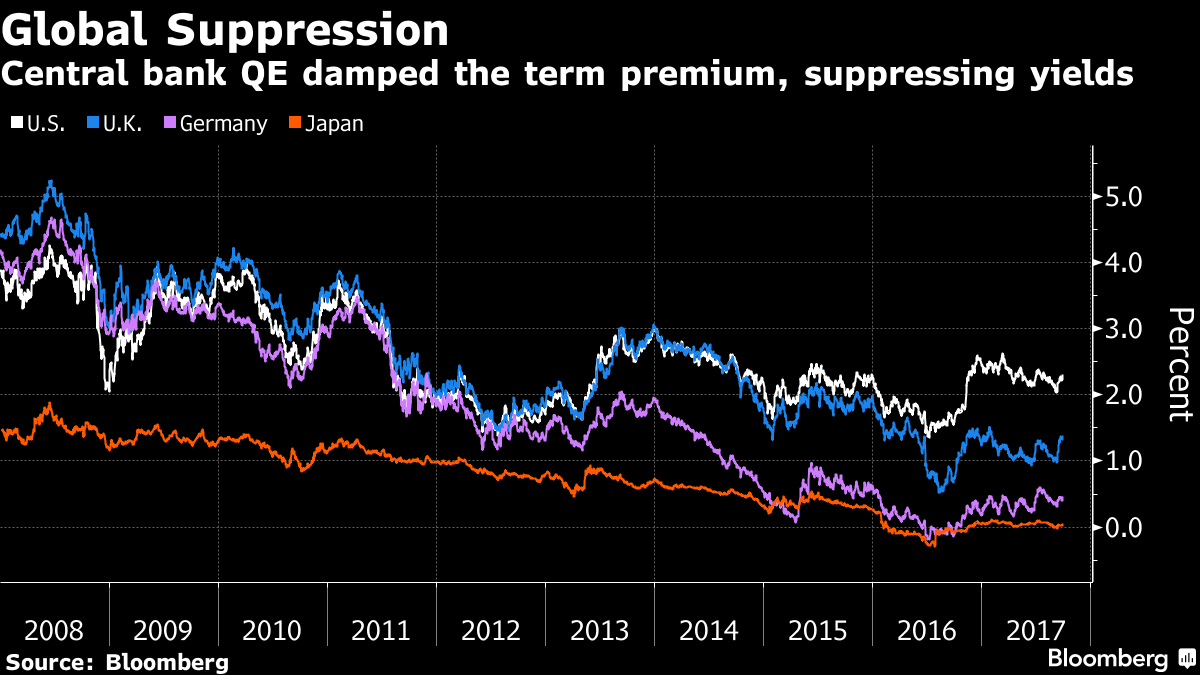

While the Fed’s quantitative easing suppressed yields and erased the margin of safety which investors have historically needed to own long-term Treasuries, the firms say it isn’t a foregone conclusion the opposite will happen as the central bank reverses course. If anything, that buffer, otherwise known as the term premium, may remain well below its long-run average for years to come.

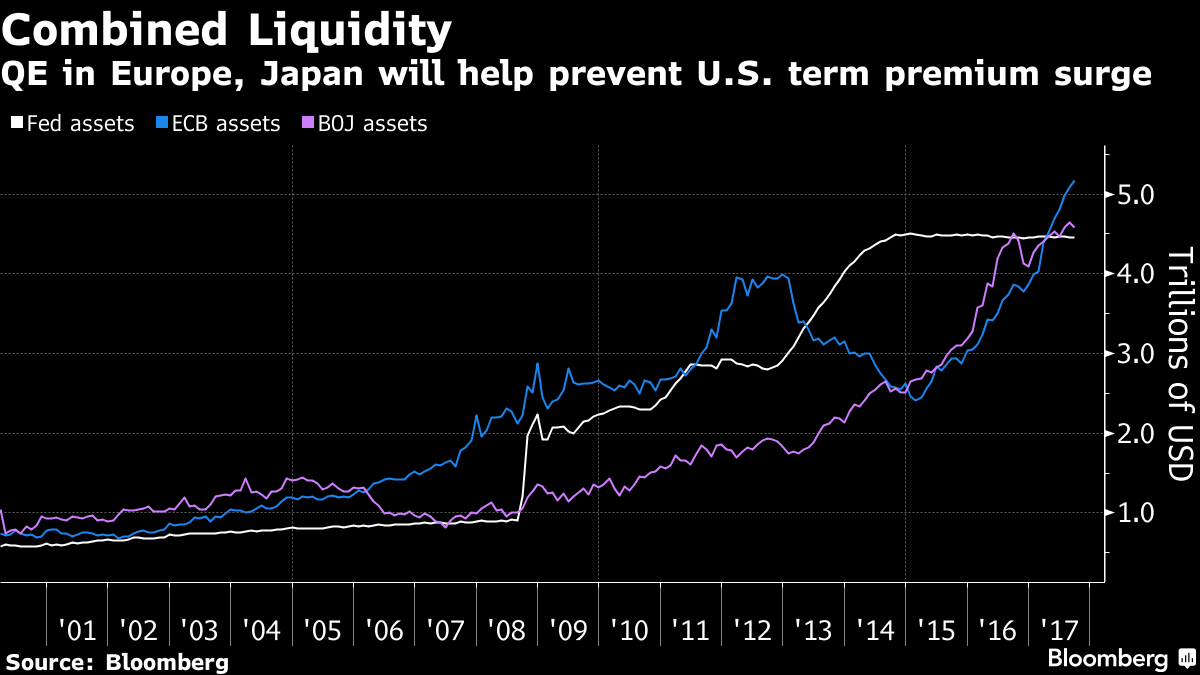

There are a few key reasons. Fed officials have already signaled the unwind will be extremely slow and the central bank will ultimately keep a significant chunk of the trillions in debt securities it amassed during QE. At the same time, easy-money policies in Europe and Japan will continue to support foreign demand for Treasuries, particularly as the Fed raises interest rates.

“It’s not to say that the term premium can never get back to historic averages,” said Praveen Korapaty, Credit Suisse’s head of global interest-rate strategy. “But that’s not a next two-year or even five-year story.”

Understanding where the term premium is headed isn’t just an academic exercise for bond wonks with high-level math skills. It’s come into focus as investors try to figure out whether the end of the Fed’s monetary experiment will finally upend the bull market in Treasuries.

Strictly speaking, the metric is the extra compensation that buyers demand to hold longer-maturity debt instead of successive short-term securities year after year, and is widely used as a valuation tool.

As the name implies, the term premium should normally be positive and has been for almost all of the past 50 years. In 2016, it turned into a discount and is now at minus 0.27 percentage point for the 10-year note.

But because it’s not directly observable, the term premium has always had a somewhat nebulous quality and is notoriously difficult to measure. (In 2014, the New York Fed itself cast aside three decades of data to produce an updated version of its widely followed model.)

According to former Fed Chairman Ben S. Bernanke, it’s one of the three main components that make up the yield for any given bond (the other two are the market’s expectations for interest-rate risk and inflation).

In his analysis, the size of the term premium reflects the buffer that investors need to account for two key risks. First is the potential for extra supply to come into the market. This would apply to the Fed’s unwind. Second is the risk of the unexpected -- that the market’s expectations, particularly for inflation, turn out to be wrong. The less certain bond investors are about their convictions, the greater the premium, and vice versa.

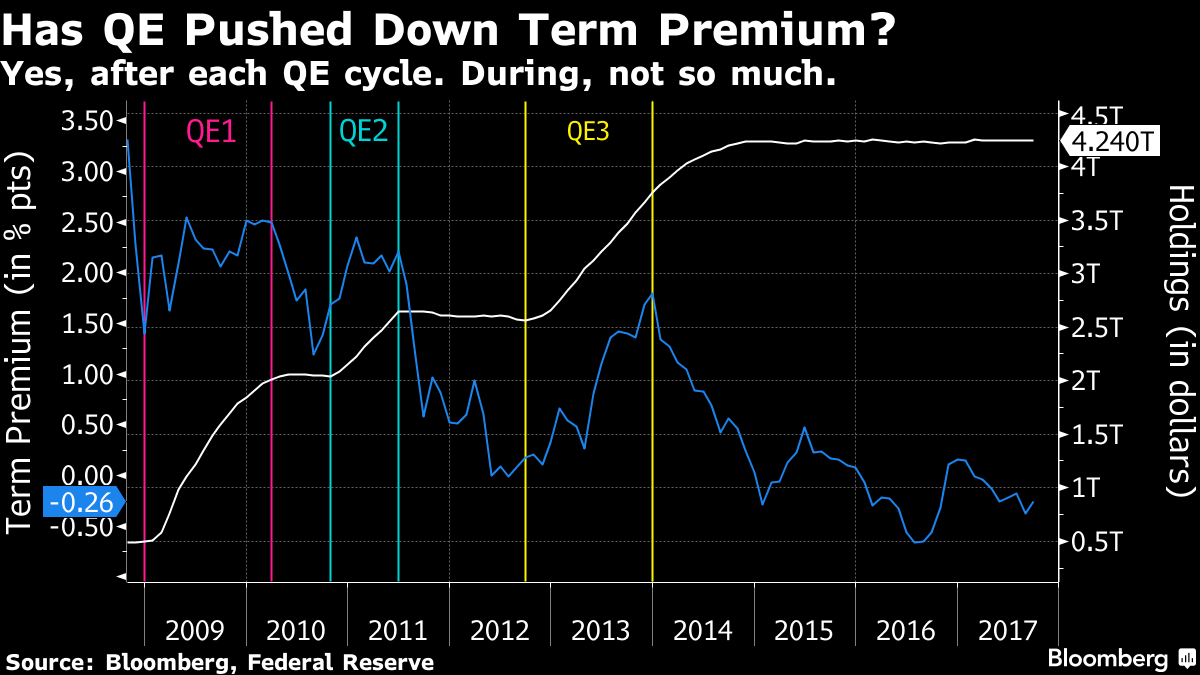

Although Fed Chair Janet Yellen herself noted last month in Cleveland that QE cut the term premium by about a percentage point, it actually rose during the periods it bought bonds and fell only after each round ended. Some say the ups and down reflect a “signaling effect,” whereby comments from Fed officials prompted investors to price in the next round of QE ahead of the purchases.

The Fed’s outsize role has provided ample fodder for bond bears who say QE has unhinged Treasuries from reality and yields have nowhere to go but up.

The term premium is a “metaphysical object,” said Francesco Garzarelli, the co-head of global macro and markets research at Goldman Sachs. “We trade a yield and then we break that down into something that reflects our expectations and something that reflects our fears that our expectations may not be met. But how we break it down is like asking how many angels can dance on the pin of a needle.”

That hasn’t stopped Wall Street from trying.

Most analysts say the Fed will trim its $4.5 trillion of assets, composed primarily of Treasuries and mortgage bonds, to about $3 trillion by letting maturing debt gradually roll off over the next several years. Because the Fed is unlikely to pare its assets down to pre-crisis levels (which equaled roughly $900 billion in 2008), that will keep a lid on how much the premium can rise.

According to estimates by Goldman Sachs, each $100 billion decrease in debt raises the 10-year term premium by two to three basis points. That would equate to roughly 50 basis points, or a half-percentage point, if the Fed’s balance sheet returned to pre-crisis levels.

Even in that scenario, the premium would still end up at less than 0.3 percentage point, well below the historic average of 1.6 percentage points. Deutsche Bank sees it rising just a quarter point through the end of next year, while Credit Suisse estimates a half-point gain by 2021.

Nellie Liang, who led the Fed’s Division of Financial Stability until December, says she’s less focused on what a “normal” term premium might look like. Instead, she’s more concerned about the potential fallout for risk assets like stocks and high-yield bonds, which have soared, if it suddenly rises. The fact that bond investors don’t foresee any potential risks on the horizon helps to explain why financial markets have become complacent.

If the term premium jumps, “risky asset prices, which discount their future cash flows based on Treasuries, would then fall,” said Liang, who is currently a researcher at the Brookings Institution. “That seems to me to be an issue.”

Pimco’s Scott Mather says stimulus measures by foreign central banks are likely to act as a counterweight, and keep Treasuries in demand.

While the Fed tightens, the Bank of Japan will continue buying 60 trillion yen ($532 billion) of assets a year, according to JPMorgan Chase & Co. The European Central Bank, which is debating whether to scale back stimulus, is still expected to buy about 20 billion euros ($23 billion) a month during the second half of 2018. All told, global liquidity is poised to increase next year.

“There is probably not as much focus as there should be” on global monetary policy and its effect on U.S. yields, said Mather, Pimco’s chief investment officer for core fixed-income strategies. That’s partly why “we don’t really expect it to get back to average levels of term premium anytime soon.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Liz Capo McCormick in New York at [email protected] To contact the editors responsible for this story: Boris Korby at [email protected] Michael Tsang, Mark Tannenbaum