(Bloomberg Opinion) -- If you’re just waking up to the snapback rally in Treasuries, you’ve probably missed the fun. Since Oct. 19, 10-year Treasury yields have dropped 82 basis points, erasing most of the nearly three-month 103-basis-point surge that began with Fitch Ratings’ downgrade of the US and came to a head with the outbreak of the Israel-Hamas war.

That doesn’t mean that the summer panic was a complete head fake; just that it was wildly overdone. Faced with a series of negative surprises, bond investors opted to sell first and ask questions later. Now, mercifully, we’ve entered the sober analysis stage of the cycle. And my reading of the evidence suggests the market once again has the story right (for now).

Interest Rates

There are still a lot of outstanding questions about what started the selloff in the first place, and it feels helpful to begin with what it wasn’t: a large realignment of interest rate expectations.

A very basic model of 10-year Treasury yields assumes they should reflect average interest rate expectations over the coming decade (plus some “term premium”; more on that later).

In the past several months, the near-term monetary policy debate has revolved around whether or not the Federal Reserve would push rates another 25 basis points higher to a peak range of 5.5%-5.75% and how long they would stay there. At the peak of the hysteria, futures markets implied slightly better than even odds that central bankers would tighten again. Theoretically, that shouldn’t have moved the needle on the 10-year yield by more than a few basis points. Fed funds futures show that markets completely priced out that last hike in the middle of November and, instead, now assume about 125 basis points in cuts through the end of 2024.

Another variable, of course, is longer-term policy rate expectations. Where will rates settle when the inflation fight is over and the economy has returned to steady state? For years, Fed policymakers have suggested that the long-run steady-state rate was around 2.5%, an estimate that encompasses the belief that inflation will settle around 2% and a “neutral” real rate of about 0.5% would be appropriate to keep it there. But if either of those assumptions were no longer correct, it would justify a more permanent increase in 10-year Treasury yields.

And that indeed may be the case, of course. Some investors have argued that, among other things, the world is entering a period of deglobalization — a shift that started with the populism of former President Donald Trump and was supported by the Covid-19 supply-chain debacles and, ultimately, the outbreak of major wars in Europe and the Middle East. As the argument goes, that may make the Fed’s 2% inflation objective harder to achieve.

But it’s doubtful the change is anywhere as big as the initial Treasury move suggested — at least according to the measured calculations of primary dealers. Eight times a year, the New York Fed asks its trading counterparties where they see policy rates settling in the longer run. For years, these forecasters generally agreed with the Fed’s assessment of 2.5%, but there was a clear shift upward in the survey period that closed in late October to about 2.75%. If the shift in expectations holds and we assume policy will soon tread a gradual path back to the higher “steady state,” it would imply a 10-year yield of around 3.1%.

‘Dark Matter’

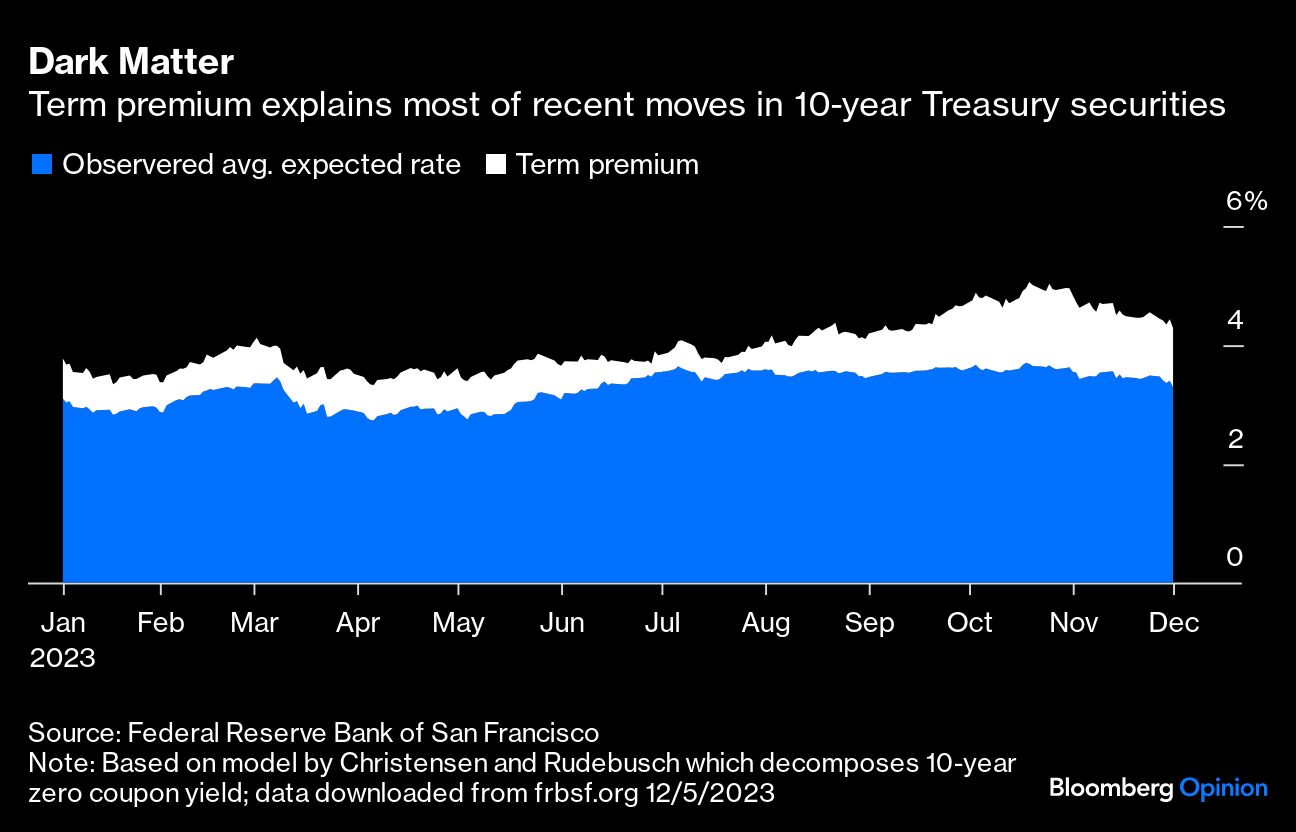

So how do we explain the additional 106 basis points (give or take) that’s baked into prevailing market 10-year yields? That’s the “term-premium” — or as Minneapolis Fed President Neel Kashkari has characterized it, the “dark matter.”

The term premium is the plug number for everything in the yield that we can’t explain. It represents your hopes and dreams; or, alternatively, your worries and nightmares — the stuff that sounds too nutty to include in your baseline forecast. It is itself very hard to quantify, and the various off-the-shelf estimates of the term premium are all over the place. But they generally all agree that the premium moved up by a lot from August through October, and has since come back down to a large degree. And it’s the move in term premium that has largely driven the overall move in yields.

Here is a popular Treasury yield decomposition model from Jens H.E. Christensen and Glenn D. Rudebusch that’s published by the San Francisco Fed:

Why did the term premium move up? Basically, it was a confluence of factors that increased that all-important fear and uncertainty. Geopolitics was clearly a near-term driver, and market participants were right to worry. As my colleagues in Bloomberg Economics recently described, the wars in Ukraine, Africa and now the Middle East have killed more than 100,000 people this year and stand to exact the biggest economic cost since the end of World War II.

For all the very real human tragedy, it’s always been hard to say exactly how these events would affect the wider global economy and, therefore, the long-run interest rate environment. Some observers may have been scared by the run-up in oil prices after Hamas’s attack on southern Israel, while others might have focused on the notion that spreading military conflicts risked hastening the move toward deglobalization, essentially putting the deflationary effects of offshoring and vibrant international trade networks in reverse.

But the initial spike in oil prices has been completely wiped out, and the deglobalization link always involved a lot of storytelling and guesswork. Meanwhile, the worst-case scenario in which the Israel-Gaza conflict spread to involve the US and Iran seems to have faded. One quantitative measure of daily geopolitical risk — an index created by Dario Caldara and Matteo Iacoviello — suggests that market uncertainty has indeed abated.

The other piece of the term-premium puzzle is the gaping US budget deficit and the related glut of debt issuance. The deficit, of course, is clearly an issue that fiscal authorities in the US must address in the long run, and it has obvious ramifications for bond yields. Understandably, many people believe that credit risk is a silly notion in the US, because the government controls the world’s reserve currency. It can print its way out of any pickle. But whether you see the deficit as a credit issue or an inflation issue, it’s clearly still a problem.

A problem for today? Probably not. At some point, the nation needs to either bump up against some extraordinary good luck — a stellar run of strong productivity and economic growth, for instance — or our leaders will have to move to a more sustainable fiscal trajectory. Yet the experience of one even more indebted nation — Japan — suggests that this state of affairs can drag on for a considerable period of time.

As bad as the US deficit has looked in 2023, it has already begun to narrow a bit as deferred tax revenues (Californians got a delay due to winter storms) have come in. No doubt, the problem would get ugly again quickly if interest rates stay higher than economic growth (driving up interest expenses faster than tax revenue), but the gradual normalization of Fed policy presumably starting next year should allay those concerns.

Decades of recent US history show that bondholders generally agree that the US isn’t a credit risk. Except for a brief period in the early 1980s, bond yields and term premia have shown essentially no relationship to the size of the budget deficit. Once in a blue moon, a compelling narrative changes that, as was the case in the early part of the Reagan administration, when investors worried that planned tax cuts and spending initiatives were wrong for an economy still contending with inflation and high interest rates.

At some point, bond vigilantes may lose patience again, selling securities to protest irresponsible fiscal policy and forcing change. But the experience of the past several weeks suggests that we’re not there yet.

So What?

No one knows what the “right” term premium is, of course. Several models put the 20-year-average premium before the Covid-19 pandemic at close to one percentage point, and that seems like as good an assumption as any for something so inherently unpredictable.

If interest rates are set to average around 3.1% over the next decade (inclusive of current rates) and the term premium settles in at around 100 basis points, then 4.1% is a reasonable guesstimate for the 10-year Treasury yield. At 4.16% at the time of writing, we’re not very far off at all. So the days of stock-like total returns in Treasury markets may be behind us for a while. That’s the thing with markets driven by sentiment and stories; if you blink, they leave you in the dust. But if, instead, the market is indeed moving into a period of more sober analysis, then boring and predictable may just be a welcome development.

More From Bloomberg Opinion:

- Second-Term Risk Trumps All Others for the Fed: John Authers

- Greenspan Could Never Make It in New Zealand: Daniel Moss

- How America Can Get Its Debt Back Under Control: Karl Smith

Want more Bloomberg Opinion? OPIN

To contact the author of this story:

Jonathan Levin at [email protected]