By Lisa Abramowicz

(Bloomberg Gadfly) --It has been a rocky year since the Federal Reserve raised interest rates for the first time in almost a decade. Next year will most likely be no different.

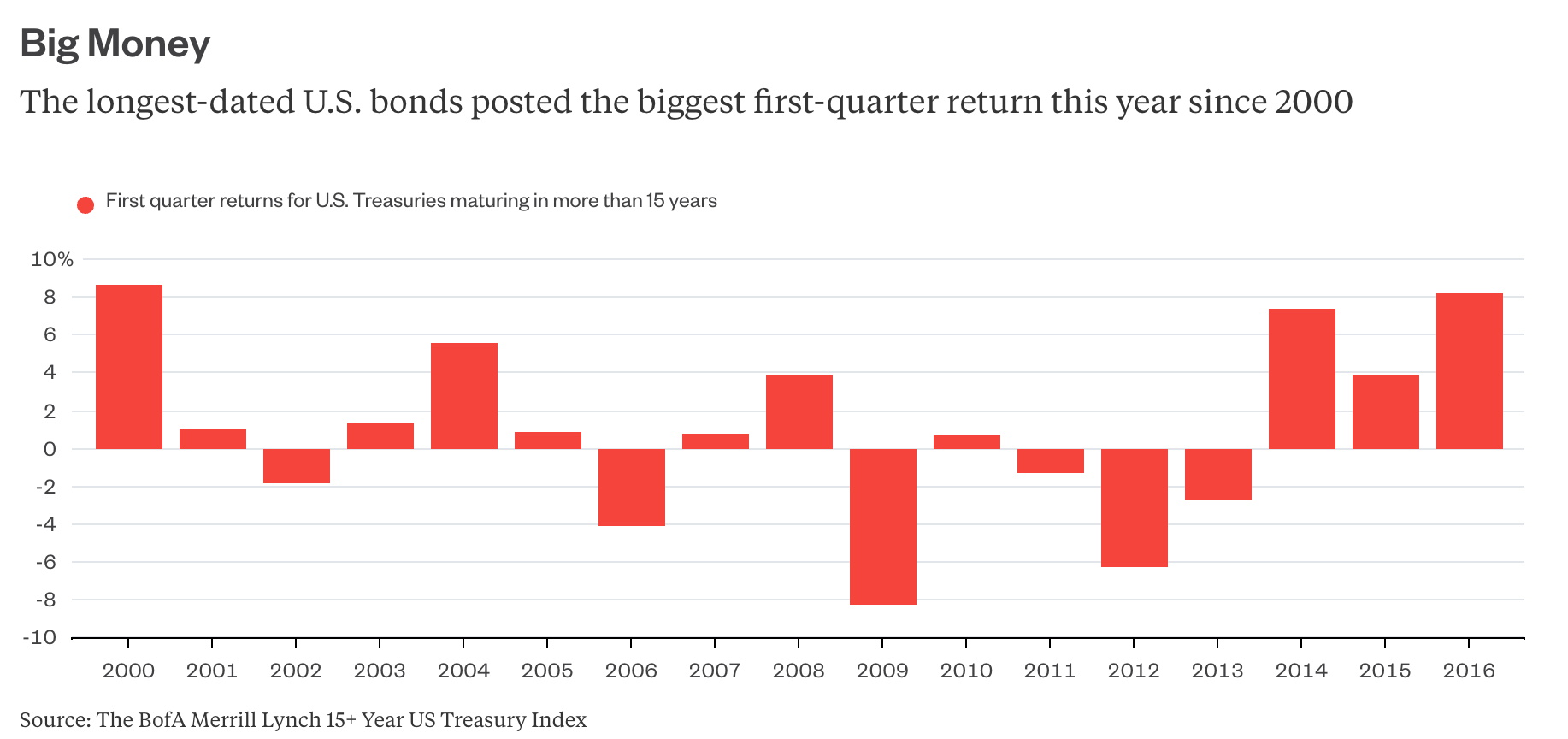

Last year's move by U.S. central bankers was supposed to herald an era of higher borrowing costs, but the exact opposite happened, at least at first. Treasury yields plunged to record lows. The longest-dated U.S. bonds rallied the most for a first quarter since 2000. People talked about potential deflation.

Then in November, Donald Trump was elected as the next president and everything changed. Bonds dived. Stocks soared. Now there is a 100 percent forecast that the Fed will raise rates again on Wednesday. Traders are again expecting benchmark yields to rise throughout next year.

But what if Wall Street traders are positioned wrong yet again? It's easy to see how that's possible.

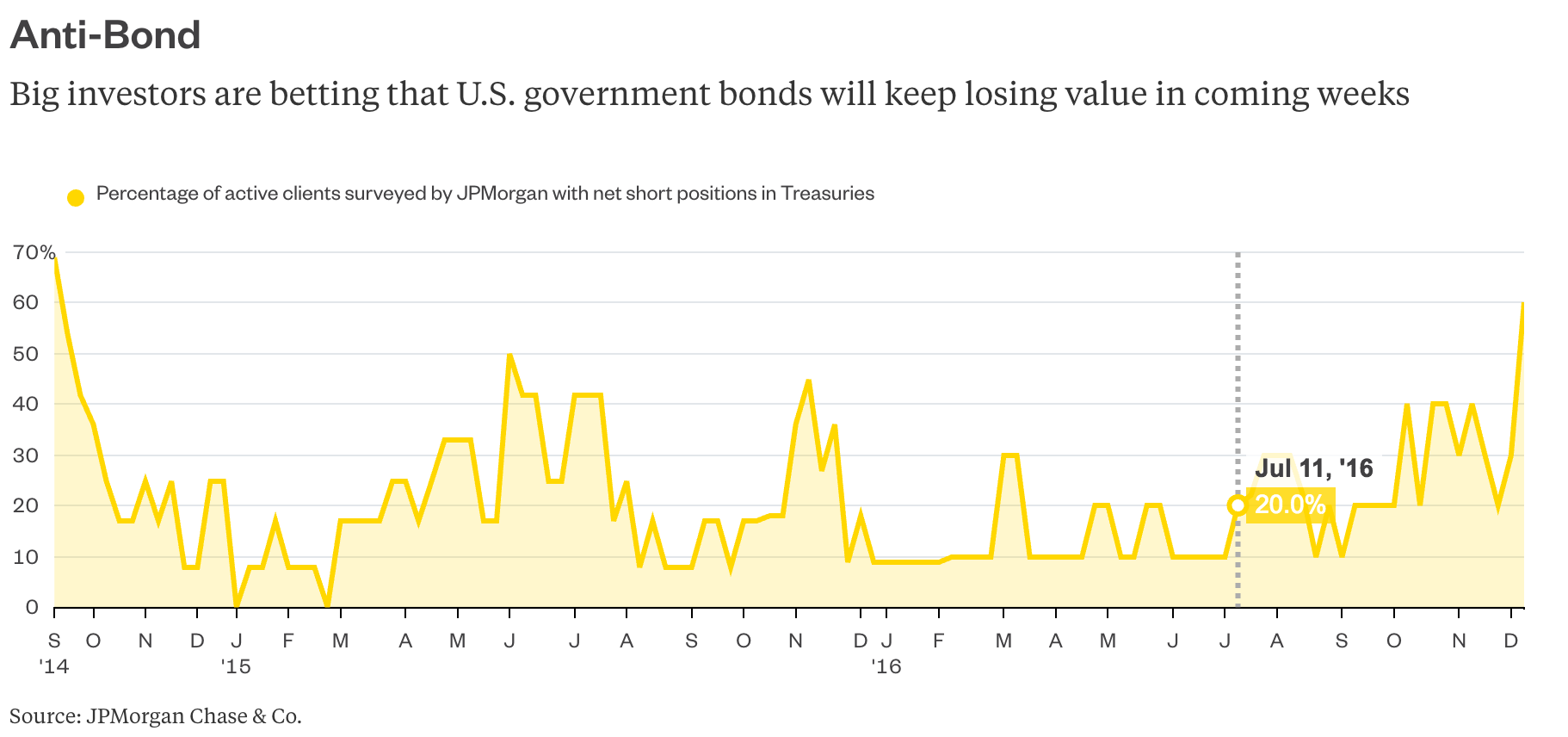

The dominant view is that President-elect Trump will swiftly enact pro-growth policies when he enters the White House in January. This would bolster riskier assets, like stocks and speculative-grade bonds, which have both been going gangbusters in recent weeks and would cause losses in classic haven investments like Treasuries. A weekly survey by JPMorgan Chase on Monday found the most short positions since September 2014 among active clients, as Bloomberg's Brian Chappatta reported.

However, Trump could find it incredibly difficult to enact meaningful initiatives within his first few months on the job. Already some key Republicans are expressing doubts about his plans. For example, U.S. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell has expressed concerns about tax cuts that would add to the deficit, saying this week, “I think this level of national debt is dangerous and unacceptable."

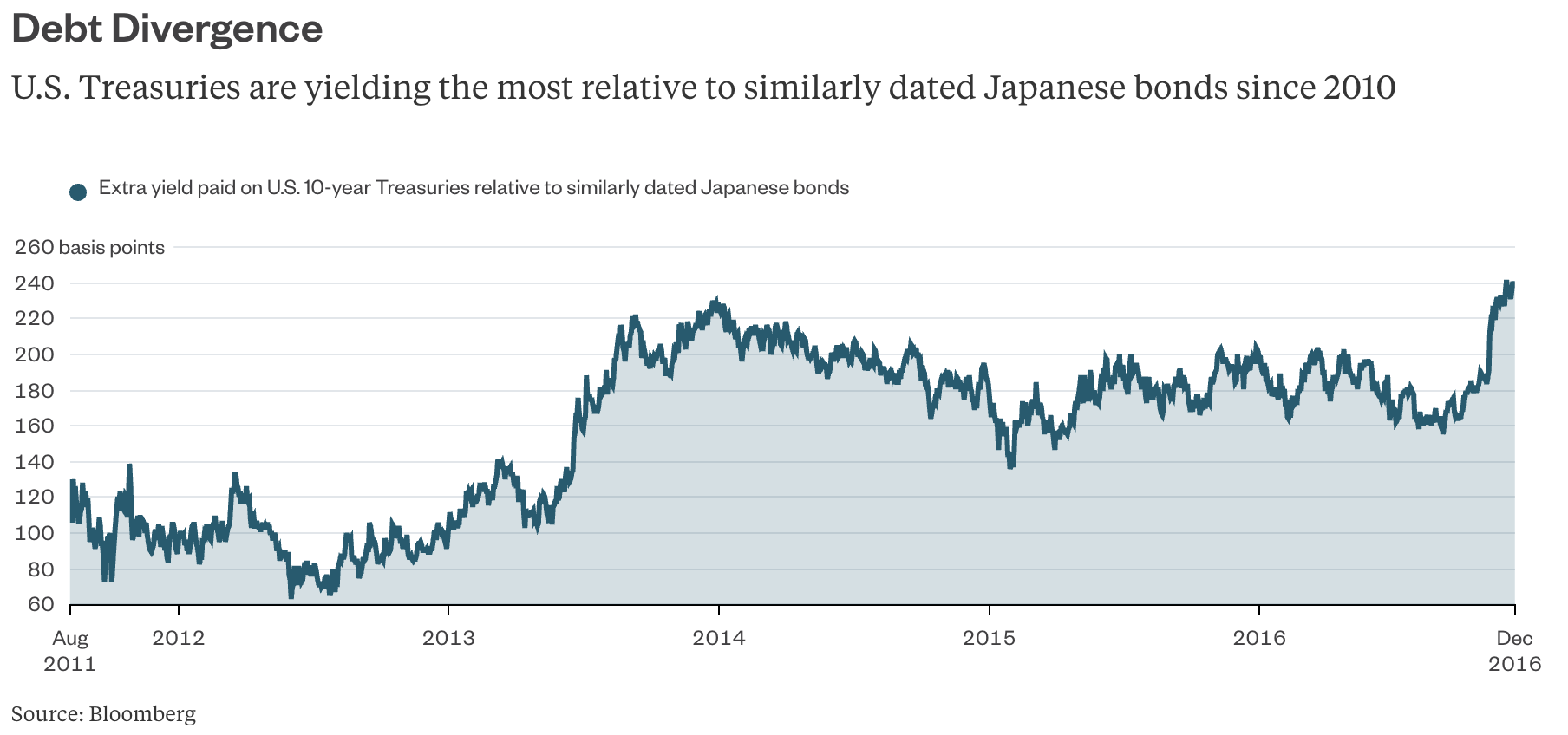

Meanwhile, one of the big arguments for why benchmark U.S. yields were so low this year stemmed from the ultra-low rates abroad. Japanese and European investors were flooding into the U.S. to capture higher returns than what they could achieve at home.

Guess what? That hasn't changed. U.S. bonds are yielding the most relative to similar German debt on record.

The dollar-denominated bonds are also offering a hefty premium over similar Japanese notes.

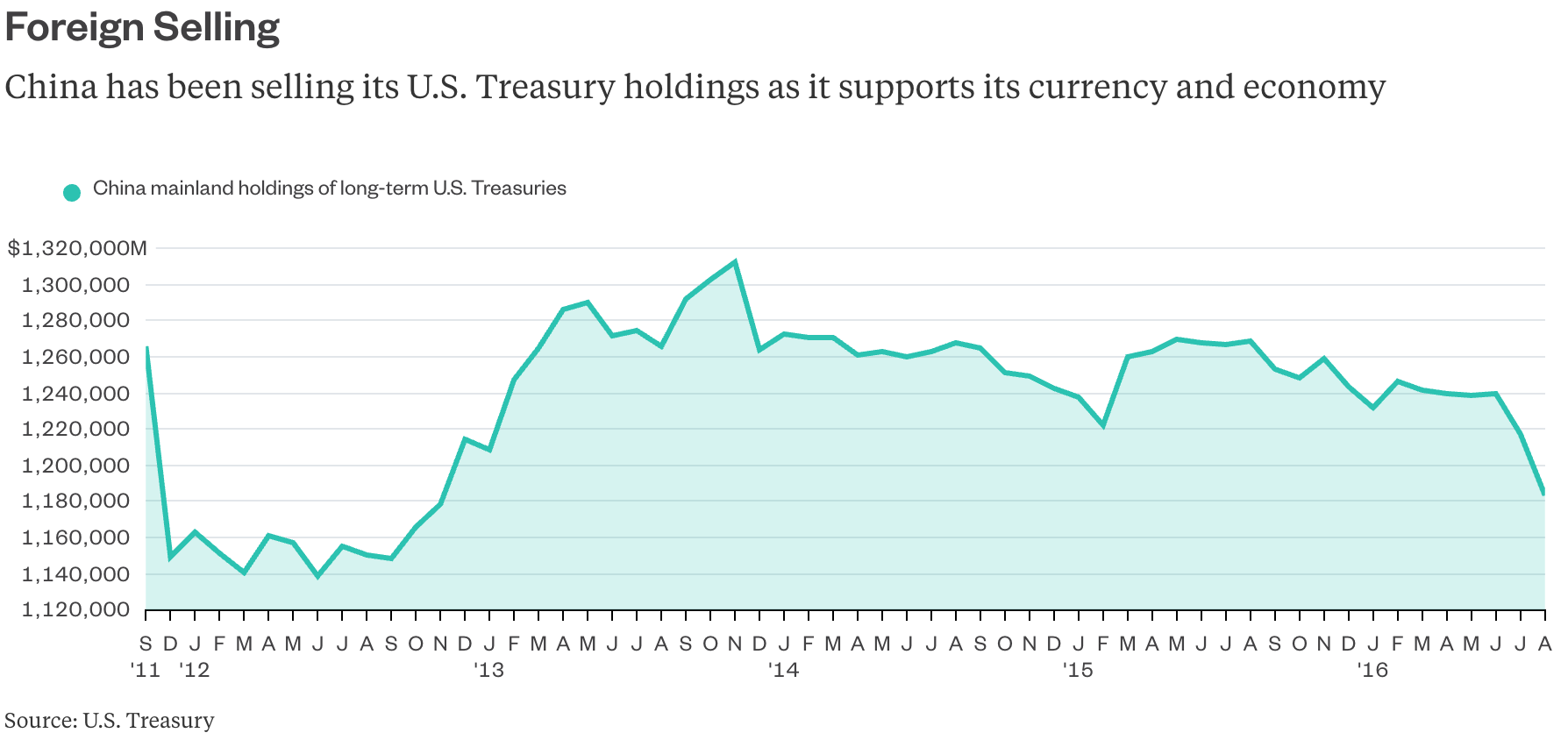

For some reason you don't hear much about those foreign investors anymore. Demand for Treasuries from overseas buyers slackened somewhat in the aftermath of the U.S. election, but that could be attributed in large part to China steadily selling its foreign-currency reserves. That is somewhat offset by private international investors looking for yield globally, and there are signs that foreign buyers are starting to return.

Then, of course, there's the issue of oil prices, which have rallied substantially, giving credence to the inflation narrative. Crude values are notoriously hard to predict and another slump would weaken the expectation of higher consumer prices.

Many investors are positioned for the recent bond selloff to continue. But they may be sorely disappointed and stung with losses in the months to come if the current optimistic mood shifts even the slightest bit. We've seen this movie before.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Lisa Abramowicz is a Bloomberg Gadfly columnist covering the debt markets. She has written about debt markets for Bloomberg News since 2010.

To contact the author of this story: Lisa Abramowicz in New York at [email protected] To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at [email protected]