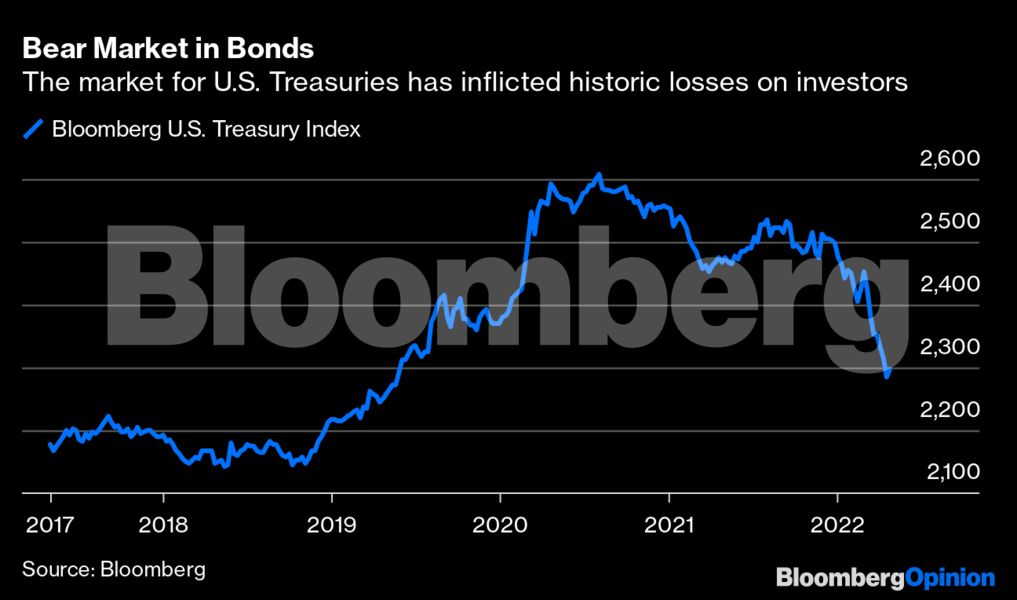

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- We are panicking over interest rates. Estimates of how high the Federal Reserve will raise its main rate to get inflation under control seem to increase daily. The yield on the benchmark 10-year U.S. Treasury note has surged 1.25 percentage points this year, inflicting historic losses on bondholders. Mortgage rates are now above 5%, increasing from less than 3% as recently as September and prompting predictions of imminent carnage in the housing market.

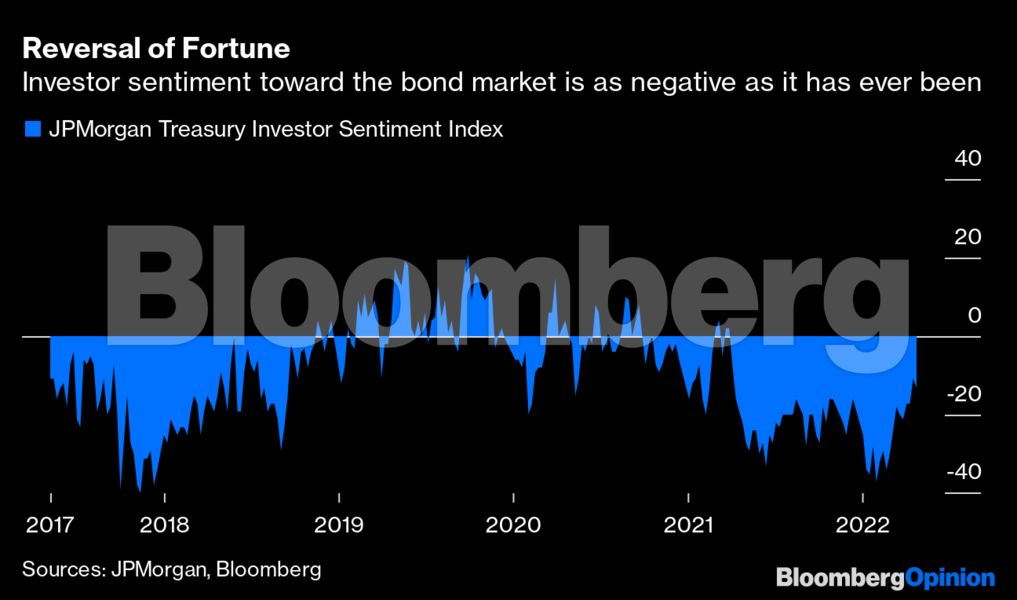

It is in times like these that I pay particular attention to sentiment, which it is expressing maximum fear about interest rates. That is good news for the bond market and anyone who is worrying about the rapidly rising cost of money, but not so much for the economy.

The first thing to know is that every time there is a rapid increase in rates, something “breaks” in the economy, causing a lot of stress and slowing growth. In 1994, it was the bankruptcy of Orange County, California, and companies, most notably Procter & Gamble Co., lost big by betting the wrong way on interest-rate swaps. That was a horrible year for the bond market, but the fallout led to a great year for bonds in 1995. And don’t forget about 1987, when 2-year Treasury yields soared through the first three quarters of the year, culminating in the epic crash in stocks that October. Again, most of 1987 was horrible for bonds, but the market rebounded in the fourth quarter and generated big gains in 1988.

The lessons from those and other episodes is that it is not so much the absolute more in rates that is a problem, but the speed. Markets need time to adjust. And while it’s always hard to predict what might “break” as a result, you always have to keep an eye on the derivatives market. The International Swaps and Derivatives Association predicted in December that the notional amount of interest-rate swaps totaled $372.4 trillion, although it’s not the notional amount that matters, but the next exposure, which is hard to measure.

Sentiment is easy to gauge in the stock market, and there are measures that range from the crude to the sophisticated. At one end of the spectrum is the American Association of Individual Investors survey, which uses a very small sample to gauge investor sentiment. At the other end are metrics such as the various put-call ratios maintained by the electronic options exchanges. Sentiment is a bit more difficult to measure in the bond market, because retail investors are basically nonexistent. One metric that does measure bond market sentiment is the JPMorgan Treasury Investor Sentiment Index. Although it isn’t flashing any warning signs, it does show traders remain net bearish even with the historic losses seen this year.

To be honest, trading based on sentiment is the ultimate in market voodoo, rooted more on anecdotes than quantifiable data. One of my favorites was when the late Jeffrey Applegate, an equity strategist at Lehman Brothers, predicted an end to the dot-com bust when he saw commercials for alpacas on CNBC. Of course, CNBC usually has commercials for online trading platforms and advisory services, so Applegate’s reasoning was that if there were ads for fuzzy livestock on the channel, then it would indicate that sentiment had bottomed in stocks. The turn happened within days.

There is also the magazine cover indicator. The Economist just ran a cover image of Ben Franklin, as he is depicted on the $100 bill, but with a facepalm under the image “The Fed That Failed,” presumably for its inability to get inflation back under control after letting it surge without acting. Inflation talk is everywhere, just like fidget spinners were a few years ago. And with the fidget spinners, one day they were there, and the next day they were gone. I am confident that inflation won’t be dominating the finance discussion in six to 12 months; it will be something else.

When markets get stretched, like they are now in bonds, it’s impossible to know or predict in real time what the catalyst will be for a reversal — it just happens. But sentiment can at least suggest that a reversal is nigh. Consider the recent quasi-capitulation of long-time uber bond bull Lacy Hunt, the chief economist of Hoisington Investment Management Co., who gained a following over the last four decades by predicting ever-lower rates. He was even predicting lower rates when they were well below 1%. Now that the inflation rate has ramped to over 8%, and market interest rates have gone parabolic, he sounded his first note of caution in recent memory, saying that “bond investors should be wary.” Hunt has a great deal of reputational capital tied up in rates remaining low, and when the biggest bond bull turns bearish, it is something to note.

It is better to be contrarian for the sake of being contrarian than consensus is for the sake of being consensus. Fundamental analysis is ephemeral— sometimes buying cheap stocks works, sometimes buying expensive stocks works. Technical indicators come and go. But the one reliable way to make money in markets through all cycles is the study of sentiment—when investors are excessively bullish or bearish, it is usually profitable to go the other way. It’s as old as stock tips from shoe shine boys in the 1920s. Human psychology hasn’t changed in 100 years, and it is predictable and exploitable. The key is to be an observer of it, rather than a participant.

To contact the author of this story:

Jared Dillian at [email protected]

© 2022 Bloomberg L.P.