The American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 (ATRA) solidified the irrelevance of the federal estate tax for all but a tiny percentage of the American population by setting the federal estate tax exemption at $5 million, indexed for inflation.1 “Portability,” which allows a surviving spouse to use any unused portion of his last deceased spouse’s federal estate tax exemption, became permanent law. As a result, with minimal planning, a married couple can now transfer nearly $11 million to their children and/or other non-charitable beneficiaries at their deaths without incurring any federal estate tax.

While ATRA decreased the reach of the federal estate tax, it increased the top income tax rate for long-term capital gains (LTCGs) from 15 percent to

20 percent. And, starting in 2013, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act added a new 3.8 percent tax on net investment income for higher income taxpayers (often referred to as the “Medicare tax”). As a result, the effective top LTCGs tax rate is now 23.8 percent (not including any applicable state income taxes).

The basis of appreciated assets that are included in a taxpayer’s estate is stepped-up to fair market value (FMV), eliminating any built-in gains on these assets.2 This is true even if the taxpayer’s estate isn’t subject to estate tax (for example, the estate is less than the federal exemption or passes to a surviving spouse).

Given the higher tax rates for capital gains, this basis step-up is more valuable than ever. Even those few taxpayers who still have taxable estates should think carefully before making lifetime transfers of assets to their beneficiaries. Although such transfers would remove the transferred assets (and any post-transfer appreciation) from their estates for estate tax purposes, the basis of these assets wouldn’t be stepped-up at their deaths. As a result, substantial gains could be recognized and taxes on such gains payable when such assets are later sold by the transferees.

It isn’t easy to determine whether the benefit of the estate tax savings that will be achieved by transferring an asset during a taxpayer’s life will likely outweigh the cost of subsequent capital gains taxes when the recipients later dispose of the asset. As we’ll discuss, the lower the asset’s basis as a percentage of its value, the more the asset must appreciate for a lifetime transfer of the asset to provide a net tax benefit.

The Trade-Off

Common practice is to make lifetime transfers of assets with appreciation potential. Such transfers are generally considered tax-efficient for a taxpayer whose estate is large enough to be subject to estate tax at death. If the taxpayer makes a gift to his children up to his available applicable exclusion, the gifted assets and all income and appreciation on those assets after the date of the gift are transferred gift and estate tax-free. If the taxpayer waits until his death to transfer the same assets to his children, only the applicable exclusion amount will be sheltered from estate tax, and any excess value will be subject to estate tax. Thus, the benefit of the gift is the avoidance of estate tax on the post-gift income and appreciation.

Taxpayers can also make lifetime wealth transfers that don’t use applicable exclusion. Such transfers are made when the taxpayer has already consumed his applicable exclusion, doesn’t want to use his applicable exclusion or isn’t willing to part with the current value of his assets and only wants to transfer any future income and appreciation. The taxpayer could transfer assets to a grantor retained annuity trust (GRAT) or sell assets to a grantor trust for his children in exchange for a promissory note. If the rate of return on the transferred assets exceeds the Internal Revenue Code Section 7520 rate (in the case of a GRAT) or the interest rate on the promissory note (in the case of a sale), the excess will be transferred to his children free of transfer tax.3

If a taxpayer transfers assets during his life in any of the ways described above, the basis of the assets in the hands of the transferee(s) will equal the basis the assets had in the hands of the taxpayer at the time of the transfer.4 In contrast, if the taxpayer waits to transfer the assets at his death, the basis of the assets will generally be “stepped-up” (or stepped-down) to the FMV of the assets as of the date of the taxpayer’s death.5 Accordingly, the cost of the estate tax savings achieved by the lifetime transfer of appreciated or appreciating assets is the potential taxes on capital gains that would be incurred in the post-death sale of those assets.

The Analysis

Given this cost, it’s important to carefully analyze whether any contemplated lifetime transfer of a taxpayer’s assets is likely to result in less overall tax than if the transfer isn’t made, and the assets are included in the taxpayer’s estate at his death. This will be the case if the post-transfer, pre-death appreciation of the transferred assets is likely to be substantial enough that the federal and state estate tax savings will exceed the capital gains taxes on unrealized gains that could be incurred by the recipients in a post-death sale of the assets. The greater the unrealized appreciation at the time of the transfer, the more post-transfer appreciation required to produce a net benefit.

The following principles underlie this analysis:

1) An individual doesn’t avoid estate tax on the value of assets at the time of a lifetime transfer.6 If the applicable exclusion will be applied to shelter a gift of the assets, then there will be less exclusion remaining to shelter the same value at the taxpayer’s death. If assets are transferred to a GRAT or sold to a grantor trust, the value of the assets will be included in the taxpayer’s estate (and subject to estate tax) in the form of the retained annuity (in the case of a GRAT) or the note or other consideration (in the case of a sale). Accordingly, the lifetime transfer avoids estate tax only on the post-transfer income and appreciation of the transferred assets. And, a GRAT or sale to a grantor trust for a promissory note creates the additional hurdle of the IRC Section 7520 rate (in the case of a GRAT) or the interest rate on the promissory note (in the case of a sale) before any benefit is achieved.7

2) Even if assets appreciate after a lifetime transfer, this appreciation may not produce enough estate tax savings to make up for the capital gains cost attributable to the pre-transfer appreciation.

Several variables affect the amount of post-transfer appreciation that will be required to offset the loss of basis step-up and yield a net tax benefit:

• Time: The more time between the date of transfer and the date of the taxpayer’s death, the less annual appreciation will be required to offset the loss of step-up (that is, total appreciation required divided by a greater number of years yields a lower annual required appreciation).

• Tax rate on capital gains: The higher the total tax rate applicable to capital gains, including federal and state capital gains taxes and the Medicare tax, the greater the amount of appreciation required to offset the loss of step-up.

• Estate tax rate: The higher the total estate tax rate (including any applicable state estate taxes), the less appreciation that’s required to offset the loss of step-up.

• Basis as a percentage of asset value at the time of transfer: The lower the transferred asset’s basis as a percentage of its value at the time of the transfer, the more the asset needs to appreciate after the transfer to offset the loss of step-up.

Six Examples

Here are six examples to illustrate the last variable above.

Example 1: Full basis gift: Assume Bob has $1 million of applicable exclusion remaining, which he uses to make a gift of stock worth $1 million to a trust for his children. The basis of the stock at the time of the transfer is $1 million (that is, basis equals 100 percent of FMV). When Bob dies 10 years later, the value of the stock has increased to $1.5 million. Bob lives in a state without a state estate tax so the estate tax savings from the transfer is $200,000 (40 percent federal estate tax rate x $500,000 of post-transfer appreciation on the stock). If the trust is subject to capital gains tax on a subsequent sale of the stock at a total rate of 25 percent, then the loss of basis step-up at Bob’s death costs the trust $125,000 (25 percent x $500,000 of appreciation on the stock). So, the lifetime transfer of the stock yields a net tax benefit of $75,000 ($200,000 estate tax savings - $125,000 capital gains tax cost).

Example 2: Low basis gift: Now assume the same facts as in Example 1, except the stock’s basis at the time of the transfer is $100,000 rather than $1 million (that is, basis equals 10 percent of FMV). The estate tax savings from the transfer is still $200,000 (40 percent x $500,000 of post-transfer appreciation on the stock) but the loss of basis step-up costs the trust $350,000 in capital gains tax (25 percent x $1.4 million of appreciation on the stock). So, the lifetime transfer of the stock has a net tax cost of $150,000 to the trust. Despite a 50 percent increase in the value of the stock between the date the stock was transferred and Bob’s death, Bob’s children are still worse off than if the transfer hadn’t been made (and the stock had been included in Bob’s estate) because of the stock’s lower tax basis.

Put differently, with the transfer, Bob’s children net $1.15 million after the stock is sold for $1.5 million ($1.5 million - $350,000 tax on capital gains). Without the transfer, the $1.5 million of stock would have been included in Bob’s estate, $1 million of which would have been sheltered by his remaining applicable exclusion, the $500,000 balance would have triggered $200,000 of estate tax and the stock’s basis would have been stepped-up to $1.5 million. As such, no gain would have been realized on a subsequent sale of the stock for $1.5 million, and the children would net $1.3 million after taxes ($1.5 million sale proceeds - $200,000 estate tax). So, the transfer has a net tax cost of $150,000 ($1.3 million - $1.15 million).

The “appreciation hurdle” is the aggregate (not annual) appreciation required between the date of a lifetime asset transfer and the date of the transferor’s death for the estate tax savings to equal the capital gains tax cost. It’s arrived at using the following formula:

Capital gains tax rate x (1 - basis as % of asset value) / (estate tax rate - capital gains tax rate)

Only after the appreciation hurdle is achieved will the lifetime transfer provide a net tax benefit (assuming the asset would be retained until the transferor’s death). The appreciation hurdle will vary based on the total capital gains tax rate (federal, state and Medicare tax), the total estate tax rate (federal and state) and the basis as a percentage of the asset value.

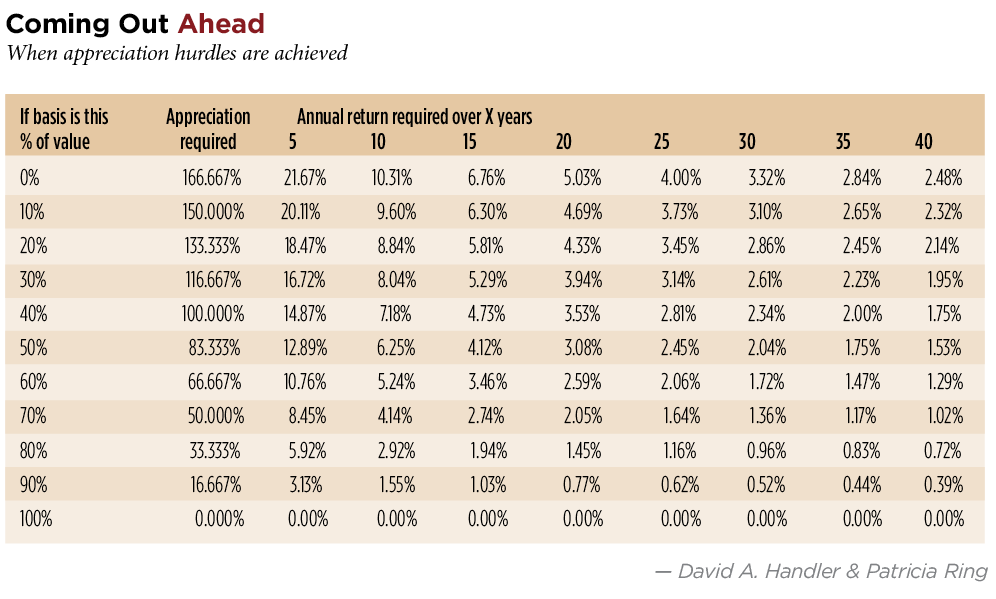

“Coming Out Ahead,” p. 49, shows the appreciation hurdles based on a total capital gains tax rate of 25 percent (including federal and state capital gains taxes and the Medicare tax) and an estate tax rate of 40 percent (assuming no state estate tax). It also shows the annual return required based on various time frames to achieve the appreciation hurdles.

For example, the chart shows that if an asset’s basis equals 70 percent of its FMV at the time of a transfer, the appreciation hurdle is 50 percent: the asset must appreciate by more than 50 percent before the transferor’s death to produce a net tax benefit from the transfer. Over a 10-year period, that’s 4.14 percent per year compounded. And, that excludes the additional annual appreciation required to beat the Section 7520 rate in a transfer to a GRAT or the interest rate on a note in a sale to a grantor trust.

Example 3: Low basis gift using “Coming Out Ahead:” Let’s again consider stock worth $1 million with a basis of $100,000 (that is, basis equals 10 percent of FMV) at the time it’s transferred during Bob’s life. “Coming Out Ahead,” this page, indicates that the appreciation hurdle is 150 percent: the stock needs to appreciate by more than 150 percent between the date of transfer and Bob’s death for the lifetime transfer to yield a net tax benefit. If the stock appreciates exactly 150 percent to $2.5 million between the transfer and Bob’s death, the estate tax savings (40 percent federal estate tax rate x $1.5 million of post-transfer appreciation = $600,000) and the capital gains tax cost (25 percent x $2.4 million of appreciation = $600,000) are equal.

If cash or another asset with basis equal to FMV (that is, basis equals 100 percent of FMV) is transferred, the appreciation hurdle is zero and all post-transfer, pre-death appreciation (or, in the case of a GRAT or sale for a promissory note, all post-transfer, pre-death appreciation in excess of the applicable hurdle rate) will result in a net tax benefit as long as estate tax rates exceed capital gains tax rates. For a transferred asset with basis less than its FMV, all post-transfer, pre-death appreciation in excess of the appreciation hurdle will result in a net tax benefit (even though the asset’s basis as a percentage of its value will then be even lower).

Example 4: Full basis gift using “Coming Out Ahead:” Consider stock worth $1 million with a basis of $1 million (that is, basis equals 100 percent of FMV) at the time it’s transferred during Bob’s life. If such stock appreciates just 1 percent to $1.010 million between the transfer and Bob’s death, the transfer will still produce a (small) net tax benefit of $1,500 (($10,000 post-transfer appreciation x 40 percent estate tax rate) - ($10,000 taxable gain x 25 percent tax on capital gains) = $1,500). If such stock appreciates 100 percent to $2 million between the transfer and Bob’s death, the transfer will produce a net tax benefit of $150,000 (($1 million post-transfer appreciation x 40 percent estate tax rate) - ($1 million taxable gain x 25 percent tax on capital gains) = $150,000).

Example 5: Low basis gift after appreciation hurdle achieved: If the stock in Example 4 instead has a basis of $400,000 (that is, basis equals 40 percent of FMV), it has an appreciation hurdle of 100 percent. If the stock appreciates less than 100 percent between the transfer and Bob’s death, the transfer will produce a net tax cost. If the stock appreciates exactly 100 percent, the transfer will produce no net tax cost or benefit. Any appreciation in excess of the first 100 percent will produce a net tax benefit. If the stock appreciates 200 percent to $3 million between transfer and Bob’s death, the transfer will produce a net tax benefit of $150,000 (($2 million post-transfer appreciation x 40 percent estate tax rate) - ($2.6 million taxable gain x 25 percent tax on capital gains) = $150,000). So, once the stock achieved the 100 percent appreciation hurdle, the additional 100 percent of appreciation achieved the same $150,000 net tax benefit as the first 100 percent of appreciation achieved for the full basis stock in Example 4.

Surprisingly, transferring a slower growing asset with a high basis may provide a greater net tax benefit than a faster growing asset with a low basis.

Example 6: High growth, low basis asset vs. low growth, high basis asset: Assume Bob wants to make a $1 million gift to a grantor trust for his children using his remaining applicable exclusion, and he’s debating whether to transfer Asset A or Asset B. Asset A is worth $1 million, is growing at a rate of 8 percent per year and has a tax basis of $100,000. Asset B is also worth $1 million, but is growing at a rate of 4 percent per year and has a tax basis of $900,000. Bob’s life expectancy is 10 years, and he doesn’t plan to sell either Asset A or Asset B during his lifetime. In 10 years, assuming Asset A and Asset B continue to appreciate at their respective annual rates, Asset A will be worth $2.15 million and Asset B will be worth $1.48 million. If Bob dies in 10 years, the net tax cost of having transferred Asset A would be $52,500 (($1.15 million post-transfer appreciation x 40 percent estate tax rate) - ($2.05 million taxable gain x 25 percent tax on capital gains) = -$52,500), and the net tax benefit of having transferred Asset B would be $47,000 (($480,000 post-transfer appreciation x 40 percent estate tax rate) - ($580,000 taxable gain x 25 percent tax on capital gains) = $47,000).

Although Asset B is growing at half the rate of Asset A, a lifetime transfer of Asset B would likely produce a net tax benefit, while a lifetime transfer of Asset A would likely produce a net tax cost. This result is because Asset A’s basis is only 10 percent of its value and, based on “Coming Out Ahead,” p. 49, it has an appreciation hurdle of 150 percent, while Asset B, with basis that is 90 percent of its value, has an appreciation hurdle of only 16.67 percent.

An even better tax result could be achieved in the foregoing example if Bob gives Asset A to the trust, and then manages to exchange Asset A for high basis assets shortly before his death (such that Asset A will be included in his estate and receive a basis step-up). This illustrates a significant benefit of using a grantor trust: The grantor can purchase, exchange or substitute appreciated assets for higher basis assets without triggering gain realization. Without a grantor trust, this option is foreclosed.

A grantor’s substitution of high basis assets for his grantor trust’s low basis assets will produce capital gains tax savings. However, if between the substitution and the grantor’s death the trust’s high basis assets appreciate substantially less than the low basis assets it exchanged, the estate tax cost of the substitution may end up exceeding the capital gains tax savings. Also, an asset swap of this nature puts the trustee of a grantor trust in the difficult position of deciding whether it’s in the best interests of the trust’s beneficiaries to part with a successful, appreciating asset to avoid the gain. This could be an especially tricky decision if the trust is generation-skipping transfer (GST) tax exempt or if any of the trust’s beneficiaries are different from the beneficiaries who would benefit from the asset the trust gave up on the grantor’s death. Of course, if the trust can use its new assets to purchase the same assets it gave up (for example, the trust uses the cash it receives in the substitution to purchase the same stock it gave up on the open market), it will be a win-win for the trust.

Gifts Triggering Gift Tax

A lifetime gift of a low basis asset on which gift tax is paid (that is, because the taxpayer has no remaining applicable exclusion) needs to appreciate far less to yield a net tax benefit than a lifetime transfer on which no gift tax is paid.8 In Example 2 above, Bob, using his remaining applicable exclusion, made a gift of stock worth $1 million with $100,000 basis to a trust for his children. When Bob died 10 years later, the value of the stock had increased to $1.5 million. The estate tax savings resulting from the transfer was $200,000 (40 percent estate tax rate x $500,000 post-transfer appreciation) but the loss of basis step-up ended up costing the trust $350,000 (25 percent tax on capital gains x $1.4 million of appreciation on the stock). So, the lifetime transfer of the stock had a net tax cost of $150,000. However, if Bob had paid gift tax on the transfer of the stock (because he had no applicable exclusion remaining), the result would have been a net tax benefit:

• Gift tax cost: Bob would have paid $400,000 of gift tax at the time of the gift (40 percent gift tax rate x $1 million gift).

• Gift vs. estate tax savings: The gift tax is tax exclusive (that is, it’s imposed only on the value of the property gifted and not on the amount of the gift tax paid). In contrast, the estate tax is tax inclusive (that is, it’s imposed on the value of the entire taxable estate including the amount that’s used to pay the estate tax). In other words, the estate tax includes a “tax on the tax.” As such, the gift tax is cheaper than the estate tax. For example, a $1.4 million outlay is required to make a $1 million gift ($1 million gift + $400,000 gift tax). In contrast, to leave $1 million at death requires a $1,666,666 gross estate ($1,666,666 - (40 percent of $1,666,666) = $1 million). Accordingly, on a $1 million transfer, the effective federal estate tax rate is 40 percent ($666,666 tax / $1,666,666 total) and the effective gift tax rate is only 28.57 percent ($400,000 tax / $1.4 million total). So, if Bob had made the lifetime gift of the stock and paid $400,000 of gift tax, Bob would have saved the 11.43 percent difference in the effective estate and gift tax rates: $114,300 (11.43 percent of $1 million savings on gift vs. estate tax).

• Capital gains tax cost after basis increase: Under IRC Section 1015(d)(6), the trust’s basis in the stock would have been increased by an amount that bears the same ratio to the amount of the gift tax paid by Bob ($400,000) as the stock’s pre-gift appreciation ($900,000) bears to the amount of the gift

($1 million). The basis of the stock would have been increased by $360,000 ($400,000 x ($900,000 / $1 million)), bringing total basis to $460,000. So, the loss of basis step-up at Bob’s death would have cost the trust $260,000 (25 percent x ($1.5 million - $460,000)).

• Net savings: The lifetime transfer of the stock would have had a net tax benefit of $54,300 ($200,000 estate tax savings on appreciation + $114,300 savings on paying gift vs. estate tax - $260,000 capital gains tax cost).

The combination of the difference in the effective estate and gift tax rates and the additional basis step-up attributable to the payment of gift tax is powerful enough to make lifetime gifts of many assets on which gift tax will be paid beneficial from a tax perspective. In some circumstances, this result will be the case even if the asset declines in value after the transfer!

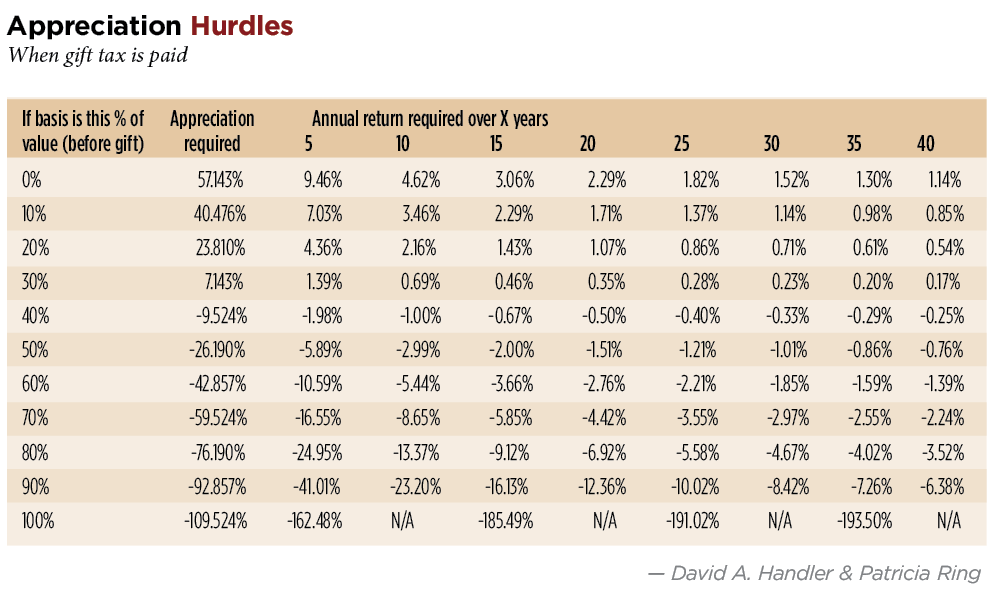

Based on a total capital gains tax rate of 25 percent (including federal and state capital gains taxes and the Medicare tax) and an estate tax rate of 40 percent (assuming no state estate tax), “Appreciation Hurdles,” this page, shows the appreciation hurdles for the estate tax savings resulting from a lifetime gift of an asset on which gift tax is paid to equal the capital gains tax cost. As you can see, if the asset’s basis is at least 40 percent of its FMV at the time of the gift, the asset can actually decrease in value, and the gift will still have resulted in a net tax benefit. At 50 percent basis, it can decrease by 26.19 percent before eliminating the net benefit.

Limitations and Caveats

The lifetime transfer of an income-producing asset will remove not only the future appreciation, but also the post-transfer income with respect to the asset from a taxpayer’s estate. And, unlike post-transfer appreciation, post-transfer income enhances the estate tax savings without a corresponding capital gains tax cost. In its current form, the model above doesn’t take this into account.

Also, it probably goes without saying that the foregoing analysis is only applicable to the assets of a taxpayer (or a grantor trust) that are expected to be retained until after the taxpayer’s death (for example, art, homes) and doesn’t apply if the gain will be recognized before the taxpayer’s death (that is, there will be no step-up).

Finally, the estate tax is a certainty and is assessed all at once. In contrast, taxes on capital gains will only be incurred if and when an asset is sold and as such, the timing of capital gain taxes can be managed and even avoided if the basis of the assets is stepped-up later by inclusion in another person’s estate. Life insurance, which is paid on the insured’s death free of income tax, can be used as a hedge against either or both estate and capital gains taxes and to eliminate the risk of a transfer with a net tax cost.

Consider Asset Appreciation

Even those few taxpayers whose estates will be subject to estate tax should carefully consider lifetime transfers of assets (even those with high appreciation potential). At current tax rates, the transfer of an asset that more than doubles in value between the transfer and the transferor’s death may not produce a net tax benefit! Always ask whether an asset is likely to appreciate enough to make the estate tax savings resulting from its lifetime transfer greater than the potential capital gains tax cost given applicable tax rates, the asset’s basis as a percentage of its value and the taxpayer’s life expectancy. Depending on these variables, the proper advice might be not to make any lifetime asset transfers at all.

Endnotes

1. The 2017 estate tax exemption amount is $5.49 million. Revenue Procedure 2016-55 (Oct. 26, 2016).

2. See Internal Revenue Code Section 1014.

3. See David A. Handler and Deborah V. Dunn, The Complete Estate Planning Sourcebook, Sections 11.03, 11.06, http://intelliconnect.cch.com.

4. Under IRC Section 1015(a), the basis of property acquired by gift is the same as it would be in the hands of the donor (or the last preceding owner that didn’t acquire the property by gift); however, if such basis is greater than the property’s fair market value (FMV) at the time of the gift (that is, the property is depreciated), the basis is the property’s FMV for purposes of determining loss (unless the gift is between spouses, in which case pursuant to IRC Sections 1015(e) and 1041(b)(2) the donee-spouse will take the donor-spouse’s basis in all events, even if the property is depreciated). In contrast, the basis of a purchased asset is generally its cost (except an asset purchased by the transferor’s spouse which, under Section 1041, is treated as a gift). See IRC Section 1012. However, under Section 1015(b), the basis of property acquired by a transfer in trust (other than by gift, bequest or devise) is the same as it would be in the hands of the grantor increased in the amount of gain or decreased in the amount of loss recognized to the grantor on the transfer. In the case of a sale of an asset to a grantor trust, the sale is ignored for income tax purposes and as such, there’s no gain or loss recognized by the grantor on the sale. Accordingly, under Section 1015(b), the trust’s basis in the purchased assets is equal to the grantor’s basis in the assets at the time of the sale.

5. See Section 1014. If the taxpayer’s executor elects alternate valuation under IRC Section 2032, then the basis of the assets will be their FMV as of the alternate valuation date.

6. However, as will be discussed, a gift of assets on which gift tax is paid will result in some transfer tax savings on the value of the assets at the time of the gift.

7. Although it should be noted that the grantor retained annuity trust and sale for a note structures create annual hurdle rates, while estate tax savings will be based on cumulative appreciation.

8. This is true unless the taxpayer dies within three years of the gift, in which case the gift taxes paid are included in the taxpayer’s estate. See IRC Section 2035(b).