LONDON, Feb 12 Don't panic yet, but the financial market upheaval in recent days is worryingly reminiscent of when the 2008-2009 global financial crisis and the 2011-2012 euro zone debt crisis were in their early stages.

It all may turn out to be a short-lived fit of market jitters, and the financial world is a different place from the days of taxpayer-funded bank and state bailouts. Nevertheless, the size and pattern of the market moves is causing concern, and to some they smack of a "third wave" of a crisis that has periodically subsided but never really gone away.

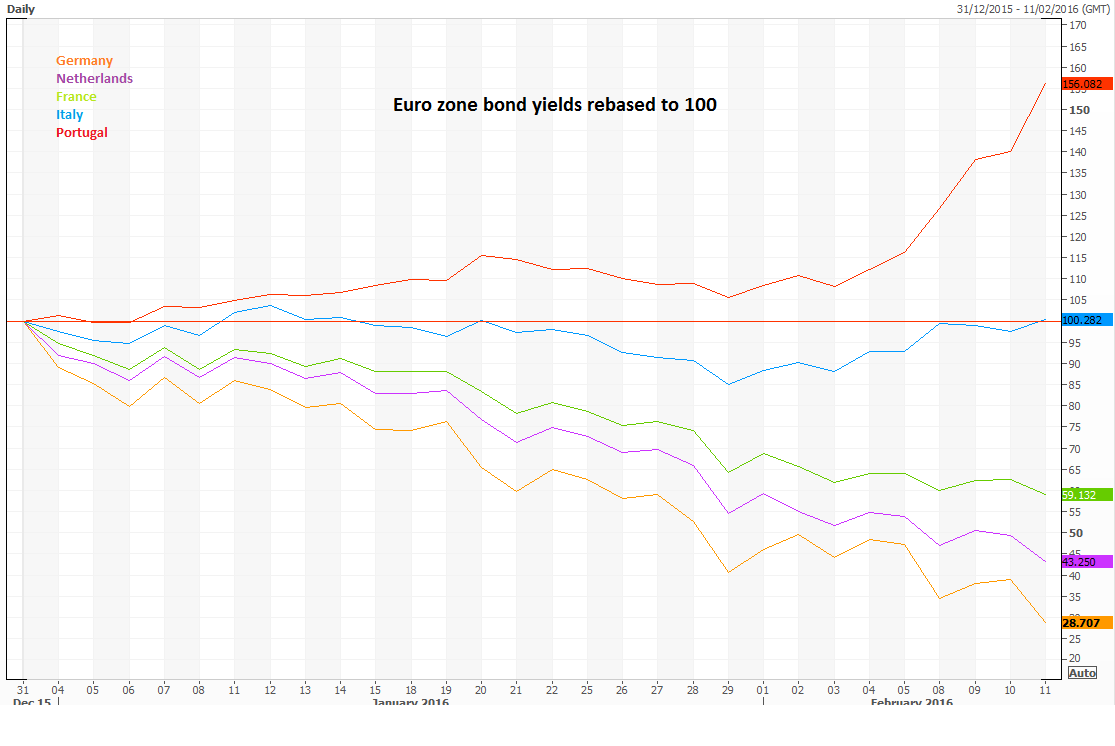

At its heart lies a sell-off of banking stocks coinciding with a steep fall in the borrowing costs of the strongest governments and jump in those of the most indebted countries - the "doom loop" that characterised the earlier crises.

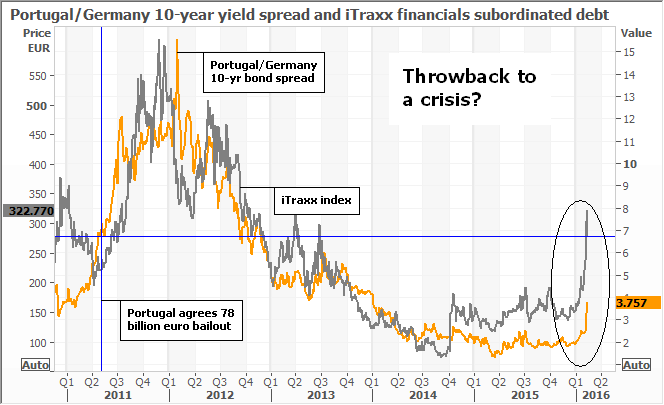

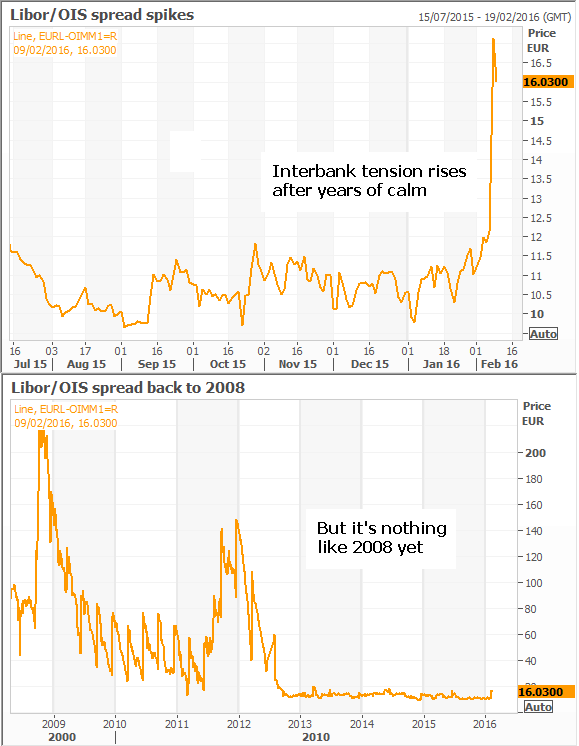

In another parallel to the bad old days, corporate bonds are under heavy selling pressure, investors are picking at the weak links of the euro zone such as Portuguese government debt, and indicators of stress in bank-to-bank lending have edged higher.

At first market commentators blamed the moves on a rapid economic slowdown in China, and a collapse in prices of the commodities that the country consumed voraciously during its boom years. This threatens the developed world with the kind of deflation that has afflicted Japan for more than a decade.

Those worries pushed down shares in energy and mining companies and then spread to the banks. Investors fretted over a possible revival of the toxic link that characterised the euro zone crisis: weaker euro zone governments relied on local banks to fund their budget deficits by buying their bonds, but then had to bail the lenders out when they got into trouble - pushing up the state's debt to unmanageable levels.

With this in mind, investors sold off Portuguese government bonds, sending the yields soaring.

All this awakens uncomfortable memories of the crises which, on some measures, began with the collapse of Lehman Brothers investment bank approaching eight years ago.

"I feel like this is the third wave," said Robin Marshall, fixed income director at Smith & Williamson. "We had the Lehman crisis in '08-09, we had the euro debt crisis in 2011-2012 and now we have the China/commodities nexus blowing out."

It is hard to draw parallels beyond the patterns of asset prices. The banking sector is more tightly regulated than in 2008. Unlike in 2011, the European Central Bank is printing money and provides a safety net in its readiness to buy the bonds of most euro zone governments.

While the Federal Reserve raised U.S. interest rates for the first time in almost a decade last December, monetary policies around the world are much looser. And yet bank shares and the "safe-haven" bonds of top-rated governments show how nervous investors are.

Whenever investors worry about banks they seek refuge in triple-A rated debt, as they did in the last two crises.

In 2008-09, European banking stocks fell more than 80 percent while five-year German borrowing costs fell 270 basis points (bps). In 2011-2012 the scale was 50 percent and 200 bps, respectively. This time bank shares are down 30 percent so far while debt yields have dropped from zero to minus 40 bps.

Inbetween the three bouts of market turmoil, at no point were banking stocks and German yields so visibly correlated.

Negativity

Across the Atlantic, Treasury yields and U.S. banks paint a similar picture. In Europe, there is another reason to worry.

The negative debt yields - driven by central banks in Europe and Japan resorting to unorthodox monetary policies to ward off deflation and stimulate economic growth - are biting into commercial banks' profits. This is rebuilding the toxic link between the banks and governments.

Sub-zero interest rates mean the banks must pay to park cash at the central bank, but those costs are difficult to pass on because customers can withdraw their deposits and leave the banks with big holes in their balance sheets.

Banks can buy short-term government bonds to avoid the central bank penalties, which are designed to encourage them to lend the money into the economy and promote growth.

But almost half of euro zone government debt now has negative yields. Lending to the real economy is not that attractive either: benchmark 30-year yields, which influence mortgage interest rates, are below 1 percent.

Weak Links

At the other end of the credit spectrum, bond investors are singling out junk-rated Portugal as the euro zone's next weak link, just as in 2011, when it followed Greece and Ireland in seeking an international bailout.

Portuguese bond yields have nearly doubled this month and at this pace would take only weeks before reaching levels at which Lisbon was locked out of the market.

ECB President Mario Draghi essentially ended the euro zone crisis in 2012 by promising to do "whatever it takes to preserve the euro", leading to a narrowing of yields on the debt of the strongest and weakest members of the currency bloc.

This re-convergence is now reversing and if the trend continues, another country could soon join the Portuguese sell-off.

"I'm not going to say I'm going to sleep well tonight," said David Keeble, global head of fixed income strategy at Credit Agricole in New York. "It's a different scale but it smacks of similarity with the 2012 debt crisis.

"A lot of water has passed under the bridge since those days ... but it's never the same so we can't be absolutely sure that there's not something we haven't thought about and it's going to bite us."

Keeble overall thought it was an episode of market jitters rather than a new crisis, and other stress indicators are still far from signalling crisis.

Strains in bank-to-bank lending, at the centre of the 2008 banking crash, hit their highest levels this week since mid-2014 in the euro zone and mid-2012 in the United States, but were still 10-20 times lower than their peaks.

These days, loose central bank policies mean banks are awash with cash.

"We don't think it will end up with the world economy coming off a cliff," Commerzbank rate strategist David Schnautz said.

(Additional reporting by Dhara Ranasinghe; Graphics by Nigel Stephenson and Marius Zaharia; editing by Nigel Stephenson and David Stamp)