by Ben Bartenstein and Ye Xie

(Bloomberg) --Jeremy Grantham, the 79-year-old investor known for his bearish views, is so bullish on emerging-market stocks that he’s telling his own kids to invest more than half their retirement money in the asset class.

"What I would own is as much emerging-market equity as your career or business risk can tolerate," Grantham, co-founder of GMO, the Boston-based asset-management company, told investors in a letter last month. It’s the only investment arena with a realistic shot at delivering 4.5 percent real returns annually over a decade, he said.

Grantham, who correctly predicted in 2000 that U.S. stocks would lose ground for the next decade, joins a growing chorus of fund managers who have become bullish on the emerging world. Peter Oppenheimer, the Goldman Sachs chief global equity strategist who forecast last month’s selloff, says stocks should rally this year, led by developing nations. Barbara Reinhard, the head of allocation for $224 billion in assets at Voya Investment Management, expects outperformance for years to come.

"Emerging markets are the place you want to be over the next five years," Reinhard said on Bloomberg TV last week.

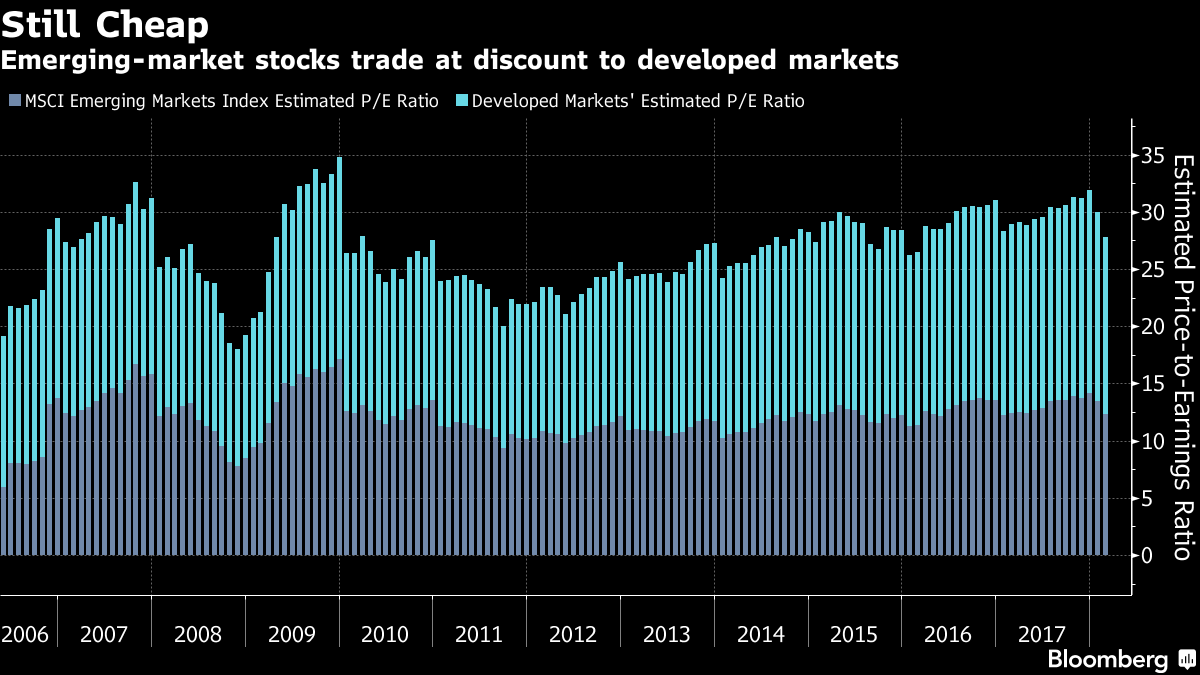

Grantham points to a growth differential and valuation gap that favor developing nations over advanced economies. His $74 billion investment firm’s forecasting model suggests that they’ll lead returns during the next seven years. Emerging economies will grow by at least 5 percent per year through 2019, more than double the pace of developed nations, according to Bloomberg composite forecasts. GMO also points to fewer " fragile" nations, attractive currency valuations and declining inflation rates.

A wholesale change of the political guard is helping. In December 2015, Argentina elected as president Mauricio Macri, a former banker and chairman of the soccer club Boca Juniors, who dug the nation out of a messy 15-year debt crisis. That was the start of a string of victories by market-friendly candidates across Latin America: Ex-Wall Street banker Pedro Pablo Kuczynski won the Peruvian presidency the following June and Michel Temer took control of Brazil that August after Dilma Rousseff’s impeachment.

Elsewhere, South Korea booted its scandal-marred leader Park Geun-hye. On the African continent, Robert Mugabe ended his 37-year rule in November. Jacob Zuma, whose nine-year tenure as president of South Africa was blemished by corruption and policy missteps, resigned last week. That drove the rand to its highest in almost three years.

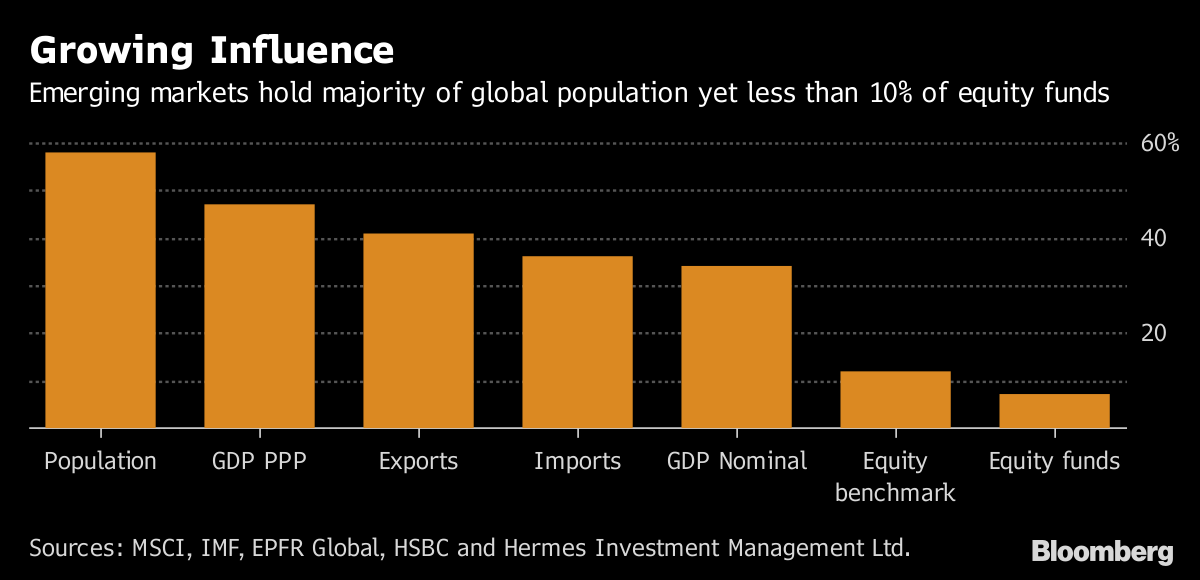

And there’s still room to grow. While far more people live in emerging-market nations and their frontier cousins than in developed ones, only a fraction of the world’s equity funds invest in them.

The backdrop for emerging-market debt is less rosy. Matt Kadnar, a member of GMO’s asset allocation team, said the firm trimmed its holdings as valuations became expensive before the selloff. In fact, the yield investors demand to buy emerging-market junk bonds fell below that of the U.S. for just the second time in the past five years. That suggests high-yield debt from developing nations is attracting greater demand from traditional U.S. and European investors, according to Josephine Shea, who manages the Emerging Market Debt Opportunistic Fund for BNY Mellon Corp., which has beaten 93 percent of peers over the past year.

"It is clear that the tailwinds have arrived," Gary Greenberg, whose Hermes Global Emerging Markets Fund topped 99 percent of peers over the past five years, wrote in a note to investors.

Finding pockets of value after two years of bumper returns has become more challenging. The return differential is telling: Developing-nation dollar debt has rallied 3.8 percent during the past 12 months compared with 30 percent stock gains and 10 percent returns on local notes.

Franklin Templeton’s Michael Hasenstab, best-known for his large one-way bets on emerging-market debt and currencies, said hard currency bonds look " very expensive." He favors local debt from nations undergoing economic overhauls with relative yield advantages such as India, Argentina and Mexico.

Pramol Dhawan, a money manager at Pacific Investment Management Co., said emerging-market currencies look attractive versus bonds given their cleaner positioning, cheap valuations and high carry.

GMO says client interest in developing nations has risen significantly since early 2016, when some questioned why they were even included in their portfolios. The money manager’s forecasting model, which has a 60 percent correlation with actual returns since 1994, predicts 5.9 percent average annualized gains in local currencies for emerging-market value stocks through 2025, according to Kadnar.

"They’re by far the most attractive asset class we can find," he said.

--With assistance from William Mathis.To contact the reporters on this story: Ben Bartenstein in Lima at [email protected] ;Ye Xie in New York at [email protected] To contact the editors responsible for this story: Rita Nazareth at [email protected] Alec D.B. McCabe