In the world of investing, product departments are constantly putting new spins on old ideas, confident there will always be investors looking for the next best thing that will provide outsized yield. Most of those new ideas are meant to make lots of money for the people who sell them. Less often, they make money for the investors who buy them. In the wake of the implosion of many non-traded REITs, non-traded business development companies (BDCs) have emerged as a relatively new structure that is getting a lot of attention. But with high up-front fees, limited liquidity and sometimes a reliance on leverage to goose returns, buyer beware.

“In my opinion, brokers should not be selling private anything—private placement, private REIT, private business development corporation—because it limits the flexibility, it limits liquidity, it limits transparency, and it almost always means higher fees internal,” said Joshua Brown, vice president of Investments at Fusion Analytics Investment Partners. “The only reason [non-traded BDCs] get sold is because it’s product and it’s sexy and it’s a way for a broker to get a higher fee for the same dollars that they would put into a public version.”

According to Tony Chereso, president and CEO of FactRight, the front-end loads on BDCs are fairly similar to non-traded REITs, which are high - typically around 11.5 to 12 percent. On top of that, BDCs also typically have an incentive structure of "two and twenty," charging two percent of assets in management fees and 20% of capital gains, based on performance.

“The downside is, it’s a huge hurdle just to get back to even,” because of the up-front fees, Brown said. “Do you know how hard it is to generate 11 percent in this day and age? With flat stock markets and Treasuries yielding 1.5 percent?”

Non-traded BDCs are pitched as high-yield vehicles, Brown said, so that’s their sex appeal. But they also exist in the public markets, "so why would you look for one outside of that? Is the yield going to be that much better? Probably not.”

New Players in the Market

Whenever a lot of new players jump on a trend and new assets are gathered, losses often follow. And lately, BDCs—the non-traded variety—are gaining a lot of new traction and interest from advisors and product developers.

“If they find that the trend is moving towards a new structure other than the non-traded REITs, I think you might see a groundswell in that direction by some people that are just taking advantage of clients looking for more non-traditional alternative investments that are maybe not subject to the same volatility that the stock market has,” said Gordon Dunne, managing director at The Financial Services Network, an OSJ of LPL Financial.

According to FactRight, BDCs have registered approximately $7.5 billion in total equity offerings. In the first quarter of this year alone, BDCs raised $655 million, up from $233 million raised in the first quarter 2011, according to data by Robert A. Stanger & Company, Shrewsbury N.J.-based investment-banking firm.

As of April, there were four non-traded BDCs available for investment and another six funds in registration. Franklin Square was the first to launch a non-traded BDC in 2008, but many players new to the space have launched funds recently, including CNL Securities, which uses Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co. as subadvisor; ICON Investment, which uses Apollo Investment Management as subadvisor; and American Realty Capital. All three firms have a background in non-traded REITs.

These new players are hoping to leverage off of the success of Franklin Square, Chereso said. Franklin Square now has $3.5 billion in AUM and three BDCs, the first of which was closed in May.

“I worry about firms that are in the real estate business, then all of a sudden they’re in the business of doing what Franklin Square does,” Dunne said. “Do you really understand credit? Do you have the wherewithal internally? Do you have a relationship with firms that have a long track record of making loans to private companies? I just hope that the BDC concept doesn’t get confused.”

Dunne’s firm invested $30 million in Franklin Square’s first BDC, FS Investment Corporation.

Just as small, inexperienced managers entered the REIT space over the last decade, Dunne fears the same thing could happen in the BDC space.

“There have been quite a few firms that have gravitated to this investment structure,” said Chereso. “Some of them have some direct experience,” such as on the publicly traded side of BDCs.

But if a firm’s core competency is in another area, such as energy or real estate, and they don’t understand credit or credit underwriting, “That causes some concerns,” Chereso said.

Many of these firms launching BDCs have strong financial positions and resources, but the question is whether they have the depth of talent and capability to manage these strategies effectively, he said.

“My biggest concern is there are lots of folks that are jumping into the space, particularly the sponsors, who don’t have a lot, if any, experience in corporate credit in writing BDCs,” Michael Forman, CEO of Franklin Square.

The Structure of BDCs

BDCs provide financing to small and mid-sized businesses. In recent years, they’ve sought to capitalize on the relative lack of debt capital in these markets, as banks restricted lending to build their capital reserves, Stanger says.

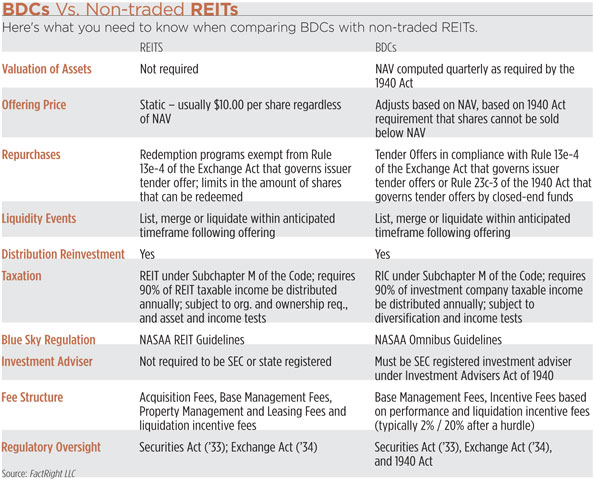

BDCs use a structure similar to non-traded REITs in that capital is raised in a continuous private offering, but BDCs are regulated under the 1940 Act that governs mutual funds. The big difference is that they’re valued quarterly, while non-traded REITs are required to publish their valuations no later than 18 months after the conclusion of the offering. (See chart below comparing other aspects of BDCs and REITs.)

“I think there’s a lot of concern and skepticism with respect to the REITs, and they look at us as being different,” said Forman. “I think we’ve kind of forced the REITs to have to change their business model a little bit.”

But they are private vehicles, so they don’t have the daily liquidity that comes with the public markets. “When you have the opacity and you’re away from the public market, your filing requirements are different, you don’t have to disclose as much financial metrics as you would if you were public; it gives you the opportunity to fudge numbers, prolong taking of losses, prolong taking of marks in the portfolio," Brown said.