By Mark Whitehouse

(Bloomberg View) --The Glass-Steagall Act, the Depression-era rule that separated plain-vanilla commercial banking from higher-octane investment banking, has come back into the spotlight as Trump administration officials suggest that they might try to reinstate it. A glance at where financial companies get their money, though, shows why the move wouldn’t address one of the system's greatest weaknesses.

Glass-Steagall has a noble aim: Limit the support that taxpayers provide to financial institutions in the form of deposit insurance and emergency loans from the Federal Reserve. It would draw the line at activities such as trading in securities and derivatives, offering support only to banks that engage solely in businesses such as taking deposits and making loans. If anything other than a bank got into trouble, the Fed would just let it fail.

Problem is, it's hard to imagine how the Fed could responsibly stick to such a promise. When, during the last crisis, the central bank provided emergency liquidity to vast swathes of the financial sector -- including insurer American International Group Inc., numerous investment banks and the entire money-market mutual fund industry -- it did so not because there was no more Glass-Steagall. It did so because those institutions were crucial to the economy and depended on short-term funding that, at a time when private investors were fleeing, only the central bank could provide.

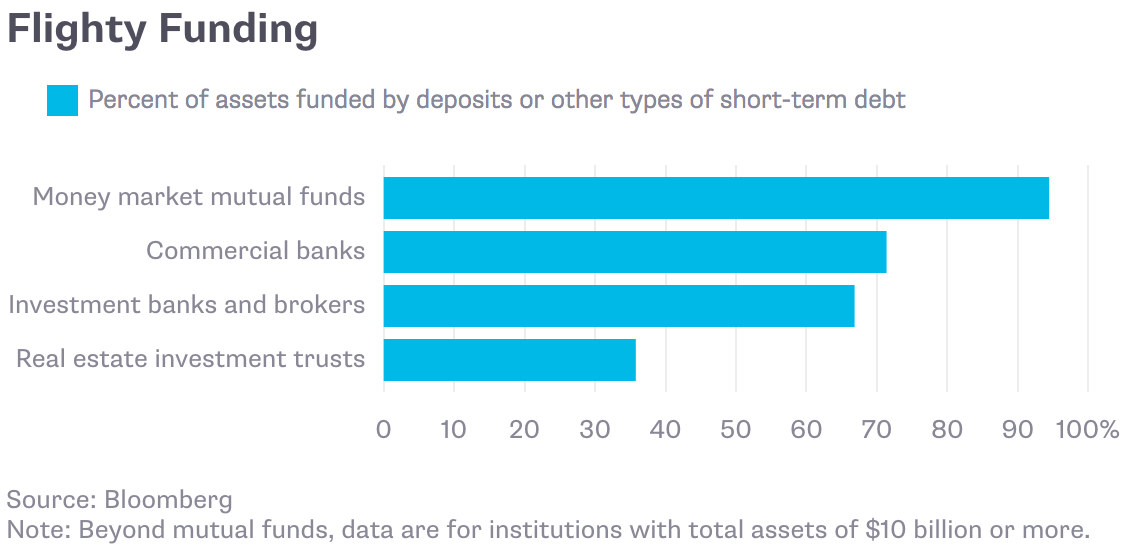

Thousands of pages of post-crisis regulations haven’t eliminated this vulnerability to runs. If, for example, a new Glass-Steagall went into effect today, institutions outside the Fed's safety net -- such as money-market funds, investment banks and real estate investment trusts -- would still rely on various types of short-term borrowing to finance more than $4 trillion in assets, or about three-quarters of all their holdings. Here's a breakdown:

Requiring institutions to finance themselves with more loss-absorbing equity capital could help a lot. The more confidence creditors have in a company’s solvency, the less likely they are to flee. Still, even solvent institutions can be vulnerable when they borrow short-term: If there's any doubt that everyone will be paid on time, each individual creditor has a big incentive to get out first.

So what to do? Increasingly, reform-minded experts --- including former Bank of England Governor Mervyn King and former U.S. Treasury official Morgan Ricks -- are coming to the conclusion that if we want to limit taxpayer support, we must also limit the use of short-term debt. King, for example, would require any financial institution issuing short-term liabilities (such as deposits) to pre-pledge assets at the Fed, in return for guaranteed access to emergency loans. By narrowing the eligible assets to, say, mortgage and commercial loans, the Fed could define precisely what kind of banking it was willing to back. It could also scrap a lot of rules designed to ensure liquidity.

Granted, this mechanism would place greater responsibility on the Fed. Deciding what kinds of assets to accept as collateral, and what haircuts to apply to riskier assets, would be a politically fraught process, affecting everything from bank profits to mortgage lending volumes. If the central bank was too lenient, taxpayers could end up bearing losses. But even in such a bailout scenario, a devastating run would be avoided -- a much better outcome than in 2008.

Such proposals are pretty radical, but no less so than Glass-Steagall. If we want a financial system that acts as a source of strength rather than a propagator of contagion, they deserve attention.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Mark Whitehouse writes editorials on global economics and finance for Bloomberg View. He covered economics for the Wall Street Journal and served as deputy bureau chief in London. He was previously the founding managing editor of Vedomosti, a Russian-language business daily.

To contact the author of this story: Mark Whitehouse at [email protected] To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Greiff at [email protected]

For more columns from Bloomberg View, visit bloomberg.com/view