By Garfield Reynolds and Adam Haigh

(Bloomberg) --Greed seems to be running the show in global markets. Fear has fled, and that may be the biggest risk of all.

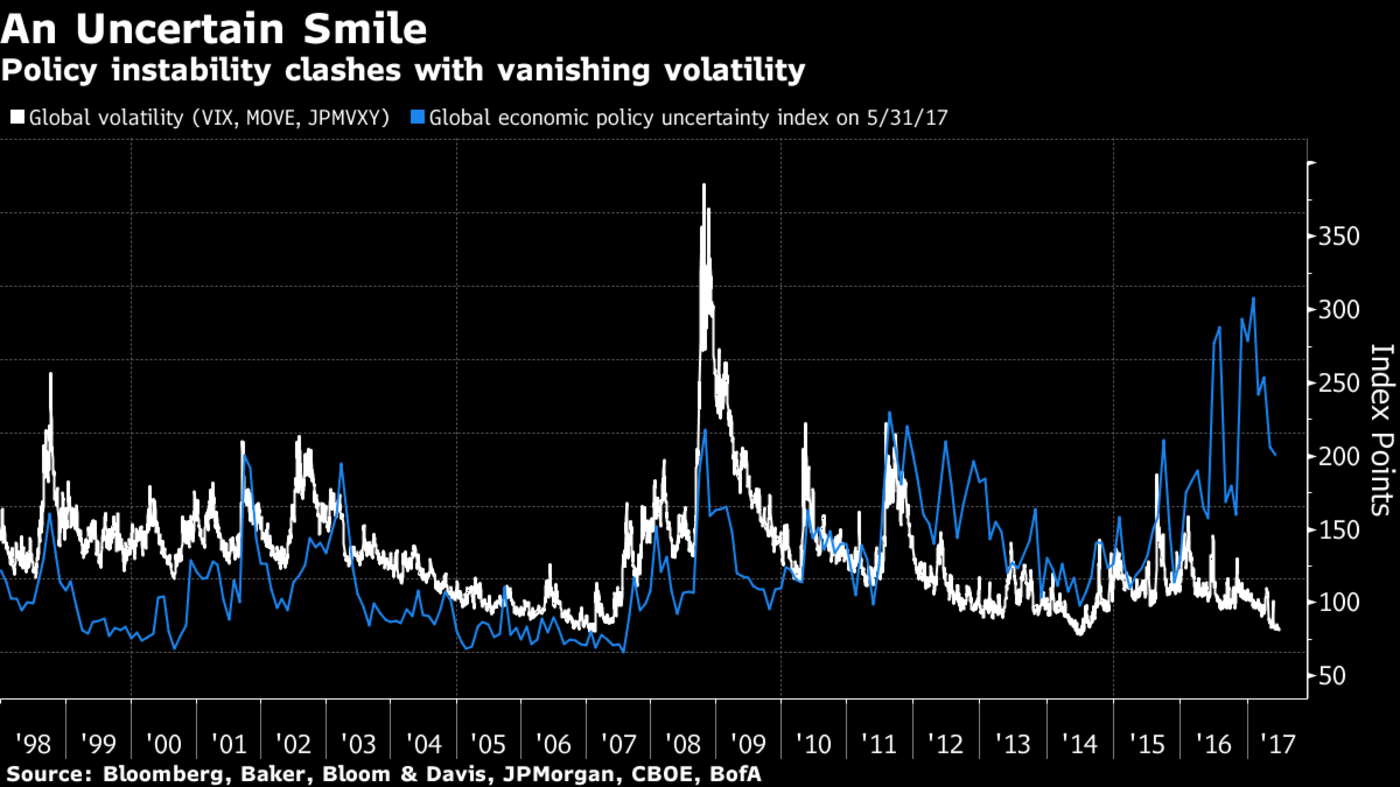

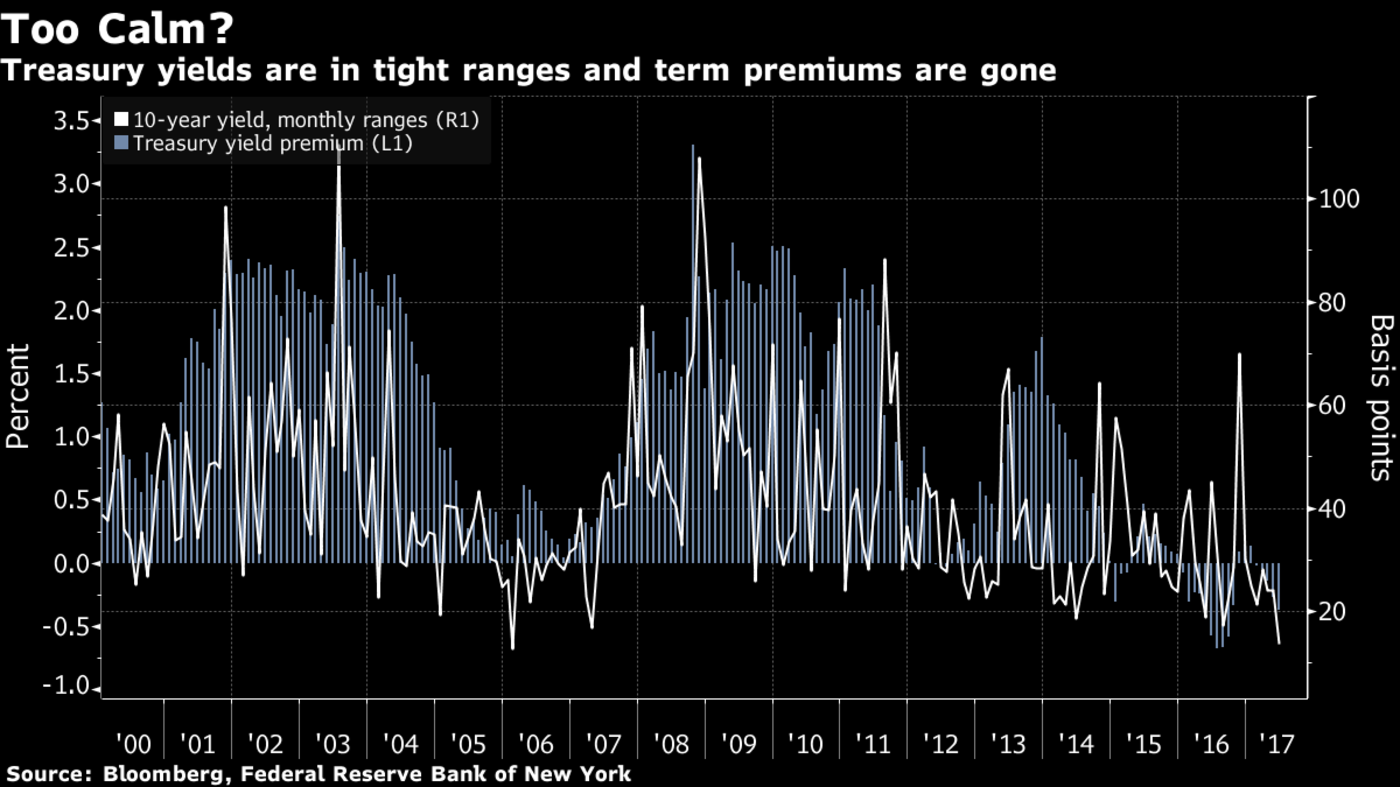

Currency volatility just hit a 20-month low, Treasury yields are in their narrowest half-year trading range since the 1970s and the U.S. equities fear gauge, the VIX, is stuck near a two-decade nadir. While markets have signaled complacency in the face of Middle East tensions, the withdrawal of Federal Reserve stimulus and President Donald Trump’s tweetstorms, the Bank for International Settlements flagged on Sunday that low volatility can spur risk-taking with the potential to unwind quickly.

The following chart shows how a proxy for global fear -- a fusion of volatility indexes on the S&P 500 Index, Treasuries and world currencies -- has tumbled as economic-policy uncertainty spiked.

“I’m uncomfortable that people are so comfortable with this,” James Audiss, a Sydney-based senior wealth manager at Shaw and Partners Ltd., which manages about $9 billion, said by phone. “I’m concerned about the very, very low volatility levels. But valuations aren’t super stretched, and companies are cashed up. It’s a new paradigm” that’s challenging people’s long-held assumptions, he said.

Some are alarmed enough they’re on the defensive:

- Olav Chen, who helps oversee almost $30 billion as global head of allocation and global fixed income at Storebrand Asset Management in Oslo, is cutting back on equities.

- Jeffrey Gundlach, chief investment officer at DoubleLine Capital LP, said this month that traders should raise cash and that the days of low volatility are probably numbered.

- Bill Gross, manager of the $2 billion Janus Henderson Global Unconstrained Bond Fund, said this month he holds a “large cash position.”

Where investors stand on the concern spectrum is to some extent driven by what they think lies behind the market complacency. Following are a range of causes detailed by market participants:

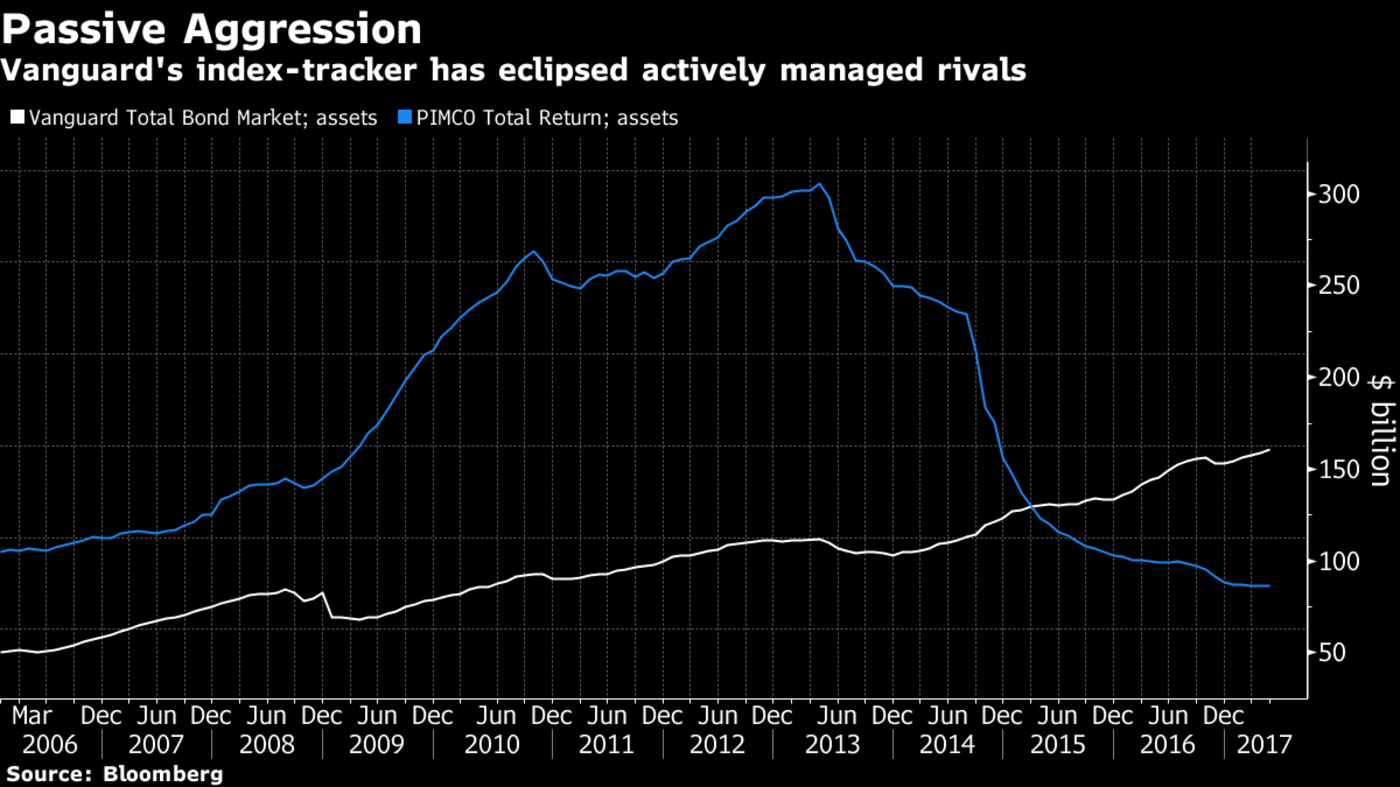

1. Passive Investors Rule

As investors woke up to how hard it was for money managers to consistently beat benchmark indexes, they also started to get allergic to their fees. So, index-trackers and exchange-traded funds have soared in popularity. Case in point: Vanguard’s Total Bond Market Index fund went all tortoise versus hare with Pimco Total Return Fund, the fund where Gross made his name as the bond king. The Vanguard fund, which seeks to match the performance of a benchmark index, in 2015 overtook the actively managed Pimco offering -- which strives to beat its benchmark -- to become the world’s biggest bond fund.

This sort of trend -- replicated across asset classes -- theoretically means a lot of the buying and selling of securities becomes more predictable.

2. Rev-it-up Regulators

Since the near-death experience of the financial system in 2008-09, regulators worldwide have moved to strengthen curbs on behavior they viewed as risky by the largest financial institutions. From big measures to small, that’s meant the banks and insurance companies that had often sought to turn large piles of cash into enhanced revenue streams by investing in all manner of higher-risk securities no longer do as much of that -- causing volatility to drop. Read the strange tale of South Korean callable bonds for just one example.

In the process, the regulators have helped make investors so eager to hold U.S. Treasury securities that the term premium has gone negative -- meaning they are foregoing any extra compensation for the risk involved in buying longer-term securities rather than shorter-term ones.

3. Low Interest Rates

Never before has so much money been lent to so many at such low rates. The yield on the Bloomberg Barclays Global Aggregate Index dropped to an unprecedented 1.07 percent in 2016 and was recently at 1.53 percent -- compared with a 9.6 percent high in 1990, soon after its inception -- and an average since then of 3.3 percent. That’s propelled investors into other, riskier, assets, boosting their prices and in turn reducing volatility. Look no further than serial defaulter Argentina managing to sell a century bond this month.

4. Rise of the Machines

Increasing use of automation and computer-run algorithmic trading has transformed global markets. Because machines are able to swiftly address any anomalies in valuations, they promote more efficient price discovery -- or so the thinking goes -- and that means fewer and smaller swings in price before equilibrium is found. Confidence in algorithms might also have diminished investor demand for options, leaving their prices lower and bringing down volatility gauges along with them.

5. Mean Reversion?

A decade after the global financial crisis erupted, markets might just be getting back to an “old normal.” With solid -- if unspectacular -- economic growth rates and contained inflation, there’s little reason for asset prices to swing dramatically. The S&P 500 index has now gone more than six months without a one-day drop exceeding 2 percent -- the longest such stretch in a decade. That still pales in comparison with the 42-month run that ended in February 2007.

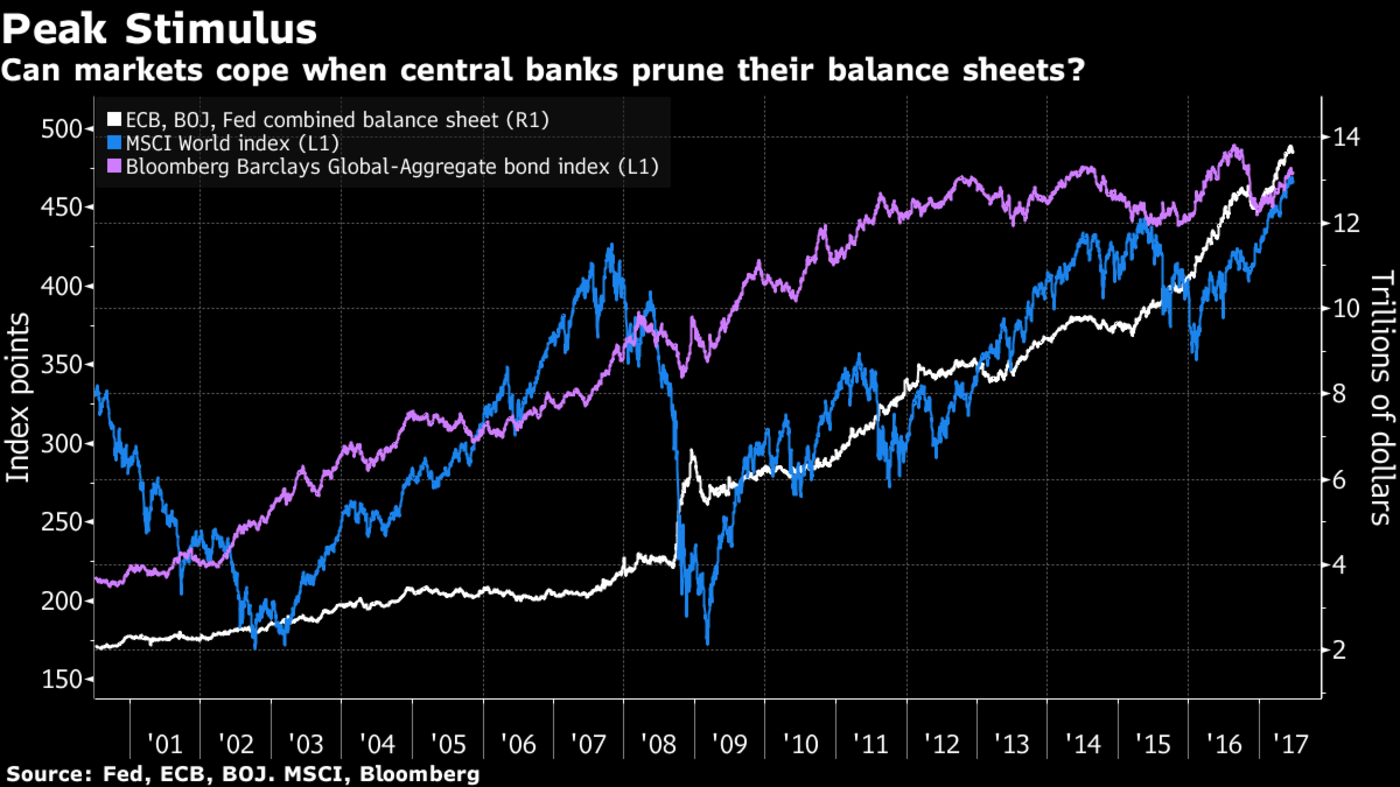

6. Quantitative Easing

Major central banks might have put a floor under global asset prices with their unprecedented balance-sheet expansions over the past decade. While the Fed’s assets topped out years ago and are now poised to fall, the Bank of Japan and European Central Bank are still accumulating securities.

This list doesn’t incorporate all the theories for low volatility, with even social media being assigned some role -- read more about that here. Which of the explanations proves most accurate may not be known until volatility returns.

Looming shifts toward central bank balance-sheet contraction would seem to have as good a chance as any other events to bring about a sea change. As the final chart below shows, the decision by the world’s three biggest monetary authorities to swell their combined balance sheets to almost $14 trillion has helped pump up stock and bond prices -- raising questions about what happens on the way down.

To contact the reporters on this story: Garfield Reynolds in Sydney at [email protected] ;Adam Haigh in Sydney at [email protected] To contact the editors responsible for this story: Christopher Anstey at [email protected] Emma O'Brien