Mutual funds changed investing. They made it possible for mainstream, nonwealthy investors to access the markets with broad diversification, professional management and the safety of a regulated fund. They propelled the careers of star portfolio managers and analysts and prompted corporate managers to grow more efficient companies for all shareholders, not just insiders. And they helped create lucrative practices for many, many financial advisors. They have long been the basis for the retirement plans of millions of Americans.

But what have they done for us lately?

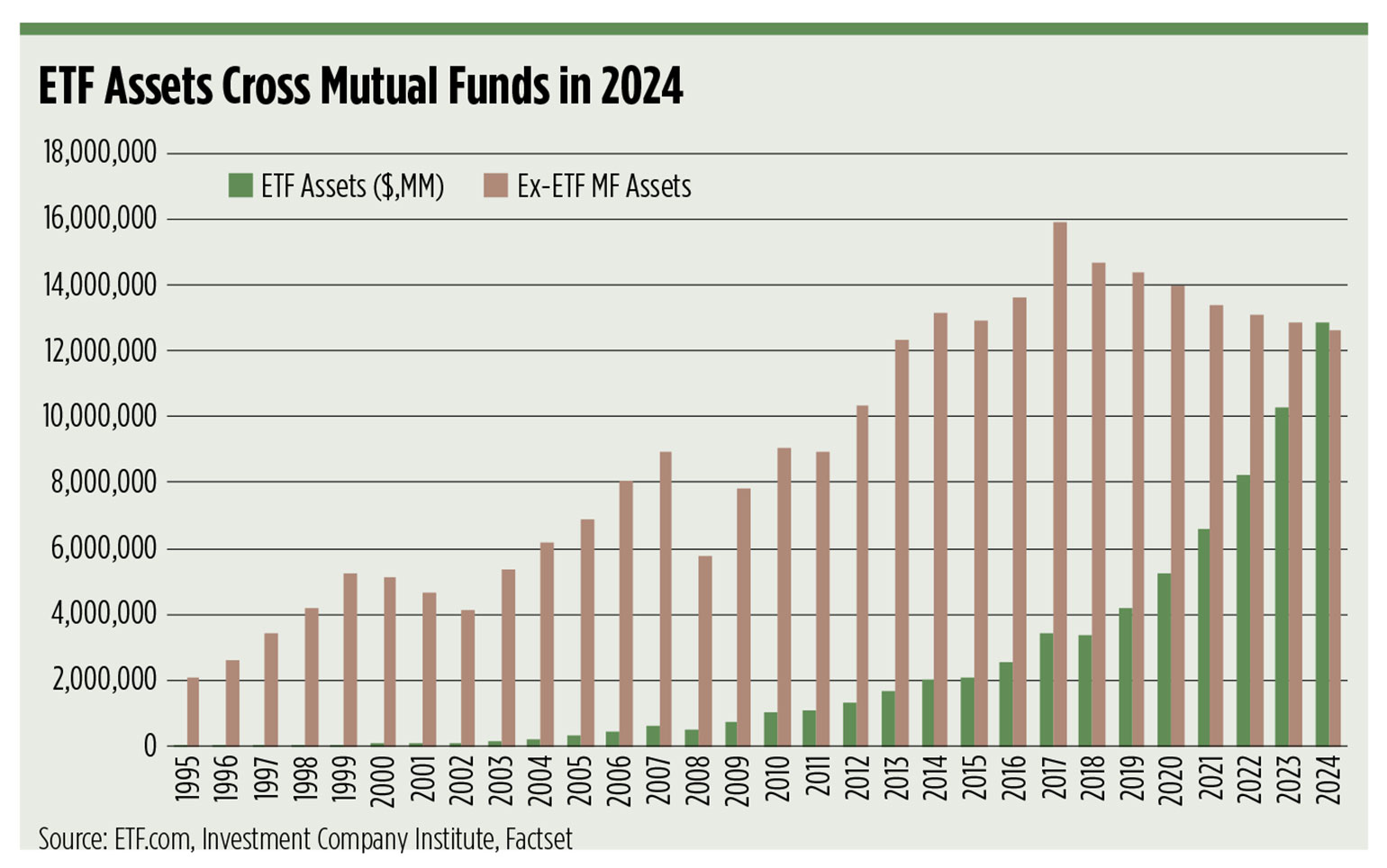

Some industry observers argue mutual funds’ best days are behind them. They’re bleeding assets in favor of exchange traded funds and separately managed accounts. The fees and incentives baked into mutual funds—good for asset managers, bad for clients—are under pressure too, as cheaper, less conflicted alternatives come into the market.

With the advent of active ETFs, some without the need to disclose a manager’s strategy, commission-free trading and the ability to make whole-dollar investments in a swath of funds via fractional shares, advisors can fairly ask: Why would anyone invest in a mutual fund anymore?

“It would certainly seem at first blush that mutual funds are slowly dying a death by a thousand cuts,” said Ben Johnson, director of global ETF research for Morningstar. “These are all forces that would, again at face value, appear to be really drinking mutual funds’ milkshake.”

MFS Investment Management is credited with introducing the first mutual fund, the Massachusetts Investors Trust, in 1924. The industry’s heyday came in the 1980s and ’90s, when stocks soared and rock-star mutual fund managers like Peter Lynch raked in assets. Assets in U.S. mutual funds were $135 billion at the end of the 1980s. By August 2000, the funds reached $7.5 trillion, according to the Investment Company Institute and the Federal Reserve. Fund companies had a larger share of assets than commercial banks.

Broker/dealers and advisors have been crucial to that story. The role of the advisor as “the distribution channel” for fund managers was well established via 12b-1 fees and trailing 12-month commissions. In the 1990s, mutual fund loads—charges levied when a fund was either bought or sold—ranged from 8.5% to 5%, according to Morningstar. But fewer advisors are happy with the transactional nature of the business and moving to financial planning as their value proposition. Asset managers have traditionally paid the brokerages back-end fees to get their funds in front of advisors and investors, but those arrangements too are coming under heightened scrutiny by the Securities and Exchange Commission.

It continues to get harder for b/ds and advisors to justify high-fee funds when lower-cost options exist.

“Brokerage firms are paring back the approved list of mutual funds, both from limited demand as well as limited resources to conduct due diligence on thousands of products,” said Todd Rosenbluth, head of mutual fund and ETF research at CFRA. “Whereas newer ETFs are coming to market on a monthly basis and, if they gather enough assets, are soon getting approved and made more available,” he said.

Advisors Falling Out of Love

Advisors have traditionally been the engine that kept mutual funds on the road. But as new money comes in the door, and younger advisors build practices, they’re finding exchange traded funds better suited to their mission as financial planners building client-centric practices.

A survey by the Journal of Financial Planning and the Financial Planning Association Research and Practice Institute found that prior to 2015, more advisors were recommending mutual funds than ETFs, but those preferences were reversed four years later. This year, 88% of advisors indicated that they currently use or recommend ETFs with clients, compared with 70% for mutual funds, according to the research. Forty-five percent of advisors said they plan to increase their usage of ETFs over the next year, compared with just 19% for mutual funds.

Among other reasons, ETFs are more portable, said Morningstar’s Johnson. They are like the Amazon Kindle to mutual funds’ local bookseller, he said.

“If I’m an advisor that custodies across three or four different platforms, I can replicate the portfolios that I’m delivering to my clients across all of those,” he said.

Neil Bathon, founder and partner of FUSE Research in Boston, argues that it’s not a fascination with the structure that’s driving ETFs’ success. Rather, advisors are trying to lower the cost of portfolio management to avoid lowering their own fees.

“Swap out this 50-basis-point large-cap core fund for a five-basis-point, or a zero-basis-point, index fund. It brings the overall cost down, and I don’t get pressure on my 1% that I charge,” he said.

The Last Corner

If price and portability aren’t the deciding factors, other developments are eating away at any remaining support for mutual funds.

Schwab, Fidelity, E*Trade and TD Ameritrade all recently cut the cost to trade ETFs, stocks and options to zero. Buying a mutual fund still comes with a fee at many brokerages. On the heels of those announcements, Charles Schwab said it would allow investors to buy and sell fractional shares, with most of the other custodians expected to follow soon.

“That will erode what I would’ve considered the last big reason mutual funds win over ETFs, which is that ability to take $300 and spread it across four or five funds,” said Dave Nadig, managing director of ETF.com. That was basically impossible to do with ETFs, he said, because of the transaction costs and the inability to fully invest a fixed-dollar amount.

Those moves also pave the way for direct indexing, allowing advisors to create a kind of separately managed account for non-high-net-worth investors.

Mutual funds have historically had a leg up in providing clients access to active managers that have avoided the ETF structure because they didn’t want to disclose their trades in real time. So firms have been working with the SEC to approve a nontransparent ETF structure that would keep the active manager’s “secret sauce” and daily trades confidential, while still benefiting from the ETF structure.

In June 2019, the SEC approved the first nontransparent active ETF model from Precidian Investments in partnership with Activeshares, which will license the structure to asset managers. T. Rowe Price, Natixis, Fidelity and Blue Tractor all recently got the nod to launch nontransparent active ETFs.

Advisors who prefer active strategies would invest in an ETF if they could, many say. More than four in five advisors (83%) hope their favorite active mutual fund becomes available in a nontransparent ETF, according to a July 2019 survey by Broadridge Financial Solutions.

CFRA’s Rosenbluth thinks we’re likely to see more nontransparent ETFs launched next year—but asset managers will be slow adopters.

“Those that already have an ETF presence, like JP Morgan or Goldman Sachs, may be a bit more aggressive, but I think they’re going to still test the waters with a couple of strategies,” he said.

Distributors are also likely to wade in with caution, said FUSE’s Bathon.

“There are things lining up that would definitely cause a lot of assets to move out of funds into ETFs, whether it’s traditional or nontransparent, but there’s probably a year of hesitation based on not having tax relief, and distributors pushing back, saying ‘let’s go cautiously into this new world,’” Bathon said.

Two SEC commissioners have also raised concerns over the nontransparent structure, arguing that in market downturns, investors won’t get a fair price for their shares, a hypothesis yet to be tested.

Perhaps the last nut to crack for ETFs is an ability to close a fund to new money. A high-conviction active manager who has, say, 10 great stock picks has a natural capacity constraint for how much money he or she can deploy before the strategy loses its edge. But if you close an ETF to new money (assuming you could), you could break the connection between the market price and the fair value of the underlying assets.

“There are lots of great mutual funds out there that have been closed to new money for decades,” Nadig said. “They tend to be more small-cap or special situations. It allows them to hold less-liquid securities. That’s the last corner. But boy does that feel like an edge case for most investors,” he said.

The Future of Mutual Funds

Actively managed mutual funds may not be taking in new money, but they still make up the bulk of advisors’ portfolios.

And the structure itself is evolving. The Department of Labor’s fiduciary rule, though ultimately not enacted, prompted asset managers to create “clean” share classes of mutual funds without the baggage of sales loads and compensation fees.

On the other end of the chain, the SEC has in recent years prompted many b/ds to voluntarily disclose and unwind past conflicts around selling more expensive share classes of mutual funds. The commission has also brought actions against some larger b/ds to shine a light on conflicts around higher-cost fund classes and undisclosed revenue-sharing deals with providers.

Last year, Morningstar found the vast majority of mutual fund flows were now going to so-called “unbundled” share classes, which charge fees for investment management and fund operations only, and “semibundled” share classes, which charge for management, operations and indirect sales distribution in the form of revenue sharing. These share classes don’t charge 12b-1 fees.

By contrast, the market share for those “bundled” share classes—which charge both indirect distribution fees as well as sales loads and 12b-1 fees—has fallen by half since 2000.

All that is for the better, but they are subtle nuances for advisors and clients more interested in a clean break than clean shares, Nadig said.

“What future there is in the mutual fund business will likely be in clean shares, but trying to understand why you should be in the clean share versus the ETF is going to be tricky,” he said.

Last but not least, most defined contribution plans are still in mutual funds. The ETF structure is making some inroads into the space, but the plumbing of retirement plans was set up for mutual funds. Some ETF advantages disappear in the 401(k) plan—most notably the tax efficiency.

Finally, even outside of DC plans, there’s a lot of money “stuck” in mutual funds—funds that advisors sold many years ago and still collect a commission. New money may be going into indexed ETFs, but the mutual funds remain the bulk of advisors’ current portfolios. There’s still hundreds of millions of dollars in high-fee index funds, largely thanks to advisor inertia.

“How do you shake that money out if it’s trapped in some retiree’s accounts, being managed by a financial advisor who’s collecting 50 basis points a year and a trail on that?” Nadig asks. “Truly I think that’s going to take a generational wealth transfer. All of the flows go into the ETF side, and that’s only going to accelerate. I see no reason that that would slow down at all.” n