We’re about to hit the 10th anniversary of Lehman’s demise, which I suspect will be the subject of some dubious nostalgia.

Let me go over my perspective of what’s changed with an eye to new, or renewed risks, suggesting that history can repeat itself.

Bear in mind that the economy and markets were well under pressure long before this benchmark event—the S&P 500 had peaked a year earlier. For context, I rebased the S&P 500 to 100 at the peak, and the day before Lehman’s demise it was just under 80 on its way to 43.6 in March. Today, it stands at 185.

In the last 10 years there’s been a reduction/consolidation of primary dealership with a consequent reduction in liquidity, providing that was offset by the simple demand for Treasurys. Then bouts of quantitative easing here and overseas soaked up the supply. Between the expansion of the crisis to Europe’s peripherals, the Greek thing and broad de-risking that kept growth and inflation subdued, interest rates ran remarkably, if somewhat artificially, low. Negative rates became a new phenomenon, even as they failed to provoke the sort of recovery they were intended to provoke.

Bank regulations, capital going to risk-taking positions and the need to hedge the massive mortgage portfolios and pipelines of the agencies while big mortgage banks have gone away, as have the jobs that went with those activities. New product creation, especially from mortgage-related areas, has really dried up, not necessarily a bad thing.

Central banks and algo funds have filled a liquidity void left by a diminished primary dealer community, and even there I sense that a handful of firms are dominating. A conference I attended a couple of years back named some of the biggest “traders” in the Treasury market, and they were firms I’d never heard of. A few large banks cited internalizing activity, like deal hedging, implying that more peripheral firms were scrambling for smaller and fewer scraps. One day there will be a need for more liquidity depth, especially with rising Treasury issuance, but that will happen at an economic/market turn, and for now, relative stability warrants complacency.

U.S. households have gotten themselves into much better shape (looking at debt service ratios), even if we consider that a lot of that was forced: people lost their homes, went bankrupt, lending standards tightened and the aging population may have found religion. In 2007, the median age here was 36.7. Today, it’s 37.9 and going north of 40, hopefully in our lifetimes. Meanwhile, the 55 and over cohort was just 30.6 percent of the population before the crisis against 35.2 percent today and a projected 36.5 percent in 10 years. Older people need less, so spend less and borrow less. The experience of 2008/09 surely scared them to follow a path that, demographically speaking, they would have followed anyway—just with more vigor.

Have no fear, people are catching up. Credit card debt is about $830 billion today versus $870 billion at the peak, while all revolving credit is $1.04 trillion over the 2008 peak of $1.02 trillion. And student lending is doing wonderfully—unless you’re the student—at $1.4 trillion, nearly triple the level from 2007, and today 30.5 percent of consumer credit from 4.5 percent in 2007.

Overall debt in the U.S. is 249 percent of GDP. When Lehman went under, it was 235 percent, rising to 250 percent at the peak of the recession. The rise, of course, is largely about federal debt at 77.4 percent of GDP (or 105.7 percent if you use the broad measure) from 40.4 percent 10 years ago (69.6 percent with the broad measure). But that doesn’t take corporations off the hook. Corporate debt is 45.2 percent of GDP, a bit higher than where it was when Lehman went bust, and a tad higher than just before the Y2K bubble burst.

This is all to say that when we look back at the next recession, it surely will be this level of indebtedness. I wonder how the recent corporate tax breaks, which will further boost the federal deficit, will stand with the household public when that happens. “Make America Great(ly) In Debt Again” could be the legacy of the last few years.

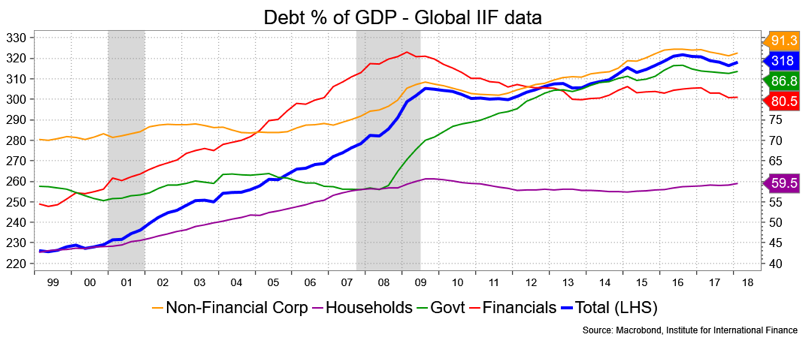

To be fair, it wasn’t Trump’s fault before this tax bill. The global story warrants its own note of discontent. Global debt as a percentage of the world’s GDP was 286 percent when we were watching pictures of Lehman employees carrying out their boxes. Today it’s 318 percent.

To all that I’ll note the rise in populism in much of the developed and underdeveloped world, which has implications I’m trying to fathom. That may prove economically good for a brief spurt to domestic economies (trade), but ultimately economically dampening and politically dangerous. Nationalism leads to economic competition, and that can lead to conflicts of another nature. “War,” to paraphrase Carl Von Clausewitz, “is a mere continuation of politics by other means.” That’s a new risk we didn’t have 10 years ago.

On a more prosaic level (I pray), we have limitations to traditional policies when we have another financial crisis or simple recession, both of which I can see as debt inspired. Interest rates are still low by historic standards, more so elsewhere in the G7, and debt, as posited above, is frighteningly high—all the more so given we’re still in expansion mode, when tradition tells us we should be paying down debt, not adding to it. The implication is that we have borrowed tomorrow to consume today and at some point that has to be paid back.

Lehman was a particular moment in time, I get that, but things had turned before then when the markets started to wake up to those debt valuations and balked, got worse with Lehman, forced government and central bank action the likes of which we’ve never seen and, 10 years on, have put debt very much back into the worry frame. I think we at least now know where to look for the cavity in the economic tooth, so to speak.

The structure of the market is also something I think has gotten too little attention. I refer to the: rise in Treasurys and duration in a bond index, rise in passive versus active investment, making indexes more of a market influence, lower credit quality on the corporate side of market (the weighting of BBB in that index), and a less defensive nature of the S&P 500, with defensive stocks holding a lower weighting. I think we need to focus on structure of markets at least as much as pure economics to guide investment strategy.

I suppose this is a way of saying that history repeats itself. If the state of debt I outline here is the cause of the next round of problems, economies will have less ability via monetary and fiscal policies to deal with them in big gun fashion. Thus, I suspect that central banks, and certainly politicians, might tolerate some inflation relief on the debt side, but I think bond and equity markets will be quick to respond.

David Ader is Chief Macro Strategist for Informa Financial Intelligence.