The jobs market is robust on so many levels, but scrape beneath the surface and there are chinks in the armor.

Demographics are the main idea—an aging population is content with working at all, with benefits and a bit of flextime at the expense of income gains. Whether you buy into that concept or not, you can’t argue with facts.

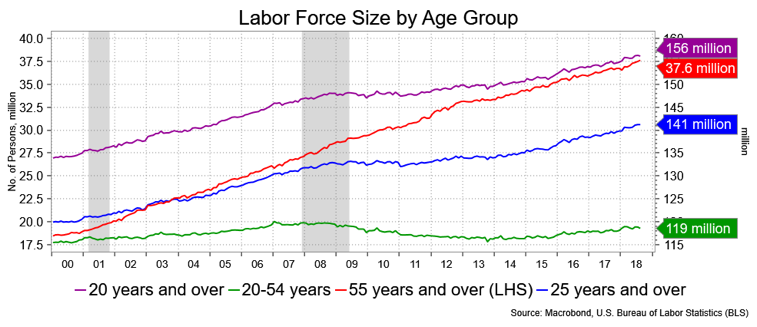

And the facts are that real wage gains are lame, the workforce and population is aging and most of the jobs are going to the older demographic cohort, begging the question, “what do they really want?”

My calculations show that those 55 and older took over 50 percent of all the job gains since early 2009. That is a remarkable achievement for older folks. Those 20-54 year olds have not fully regained the jobs they had in 2008.

There are various factors at work here, not the least of which is sharp rise in the older cohorts as a percent of the population and, perhaps, the young having had a harder time and staying in school, outside of the workforce entirely or doing something altogether different. The evidence for this broad shift can be seen in the Participation Rate by age group. Those 55+ folks are at 40.2 percent; in 2000 their participation rate was just 32 percent. Part of the story is just that the country is older, but participation rates are about a specific group relative to itself, not the population as a whole. Thus, it also shows that older people are staying in the workforce longer than ever.

Meanwhile, overall participation has fallen: from 67.2 percent in early 2001 to 62.7 percent today. The best performing participation rate lies with those 55+.

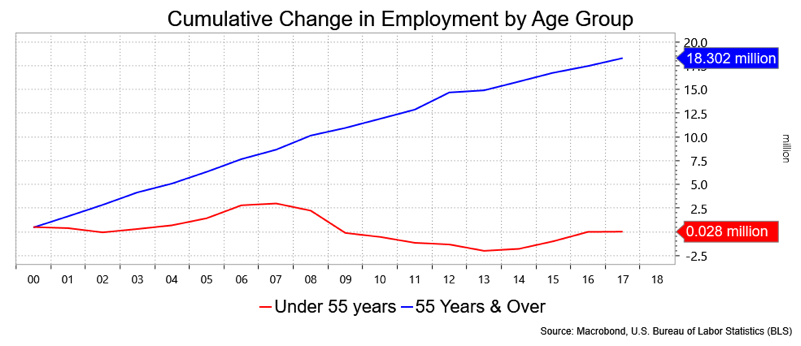

The St. Louis Fed did a piece recently that challenges some of my figures. Their report on the matter runs “Staff Pick: Older Workers Account for All Net Job Growth Since 2000.” In other words, my numbers were not as dramatic as what these Fed researchers found; “all of the net increase in employment since 2000—about 17 million jobs—has been among workers aged 55 and older.” (This next chart is a replication of the chart in the Fed report.)

The authors caution that phenomenon raises the concern about slower economic growth as a result. While older workers are more productive, the lack of younger people coming in to learn skills, gain experience, work longer and consume come to mind as long-run problems. The researchers do suggest that this trend cannot continue; people are aging at a slower rate and there is an end game to that older cohort, if you catch my drift. The report also doesn’t expect employment-to-population ratios by age group to diverge. The latter means that the employment-to-population ratio for 55+ is at 39 percent from just 31 percent in 2000, but it has fallen to 72 percent from 77 percent for those under 55. “Unlikely,” is how they put it, “although not impossible.”

For the investable future though, they still see the recent trends holding. For instance, based on Census data, they see employment by age group for 55+ moving to 23.7 percent in 2027 from 23.1 percent today, and 65+ moving to 8.4 percent of total employment from 6.2 percent today. In other words, the aging population and workforce that may have held back economic growth will give way in “the next decade or so.”

David Ader is Chief Macro Strategist for Informa Financial Intelligence.