Merrill Lynch is one of the most recognized brokerage firms in the wealth management world, with some 20,000 financial advisors across the country. It has a rich history that dates back to 1914 when Charles E. Merrill, a bond dealer founded a small investment banking firm, and later took on a partner, Edmund C. Lynch.

But the company has gone through significant change over the last several years, from being acquired by Bank of America during the 2008 financial crisis to pumping the brakes on recruiting experienced advisors. Now, after focusing on its organic growth for a period of time, the firm is back to recruiting veteran advisors, although it won’t do so by offering some of the irrational deals competitors are handing out.

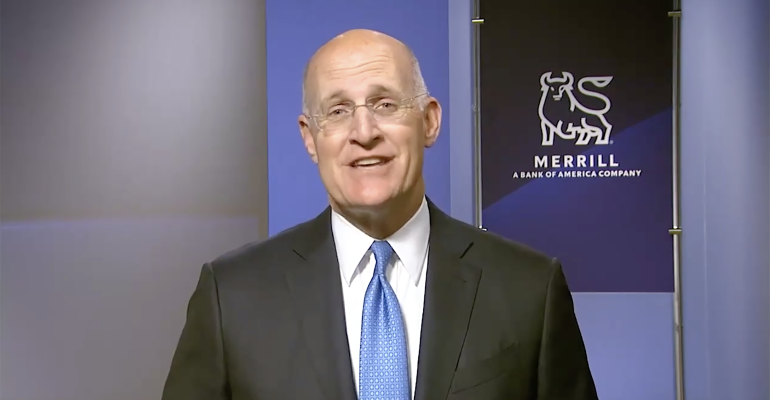

Andy Sieg, President of Merrill Lynch Wealth Management, recently joined Mindy Diamond, CEO of Diamond Consultants, on her podcast, to talk about the brokerage’s relationship with Bank of America, advisor attrition, recruiting and whether the firm will ever add an independent channel.

The following Q&A has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Mindy Diamond: Tell us about yourself, your path from the Kennedy School at Harvard to joining Merrill in 1992 to now being its president.

Andy Sieg: I went to the Kennedy School and received a master's in public policy degree. I worked in the Bush 41 White House for a couple years and then joined Merrill in 1992. So about 30 years ago, my first role at Merrill Lynch was a strategy role supporting the then head of our wealth management—we called it private client business—Launny Steffens. And over the last 30 years, I've really had an opportunity to work in most corners of wealth management in the field and in the home office, strategy roles, product roles, again, field leadership roles across the segments. And so you could look at that as being unable to hold a job for very long, or having an opportunity to see and lead in most areas of the business.

Andy Sieg: I went to the Kennedy School and received a master's in public policy degree. I worked in the Bush 41 White House for a couple years and then joined Merrill in 1992. So about 30 years ago, my first role at Merrill Lynch was a strategy role supporting the then head of our wealth management—we called it private client business—Launny Steffens. And over the last 30 years, I've really had an opportunity to work in most corners of wealth management in the field and in the home office, strategy roles, product roles, again, field leadership roles across the segments. And so you could look at that as being unable to hold a job for very long, or having an opportunity to see and lead in most areas of the business.

MD: What brought you from public policy and working in the White House to the world of wealth management?

AS: If we think back to December '92, if you were a Republican, you were being chased out of Washington. I was part of that crowd, and therefore any job was looking pretty good in December '92. But more seriously, I knew a lot about Merrill Lynch. My older brother worked at Merrill Lynch, and the then-CEO was a friend of my father's and our families, coincidentally through Penn State—Bill Schreyer. So I felt a connection to Merrill, and I was also fascinated and always have been by markets. There’s no better place to be involved in financial markets and the practical side of economics then to join Merrill Lynch.

MD: What do you think Merrill senior leadership saw in you that would put you on the road to the position of head of the firm?

AS: Looking back at my younger self, I was a hard worker. I had an ability to just generally get things done. And in a variety of early roles, I was able to find an answer, bring a project together, get it to delivery. I collaborated well with people and my communication skills have always been a strength. And very early in my career, I just had some unique opportunities to work closely with senior leadership. Dave Komansky was the CEO of Merrill Lynch in the late '90s, and I was Dave's assistant for two years. So my exposure early benefited me over the years to come.

MD: Tell us a little bit about your role as president today. What are the most important things you do today?

AS: I think of my job probably in three main areas, maybe first and foremost being the standard bearer for our culture at Merrill Lynch, ensuring that it reflects the history, but is also very forward facing and bold in terms of what we need to do with our business going forward, that Merrill continues to have the concern for our colleagues and our communities that's really typified this organization for a long, long time.

The phrase “Mother Merrill,” that's a very positive uplifting phrase for me and most of the people who work in this business, despite the fact that over the years some people tried to paint that with a negative brush.

My secondary focus is on our strategy and our direction. And here my primary focus has been trying to get this business back onto a growth footing over the last six or seven years.

And then third, in this role, as is the case for the leader of any business, a lot of focus on talent. Do we have the right people in the right leadership positions to help move the business ahead?

MD: What do you think are the most important things you do as president that impact advisors?

AS: So day-to-day, when I think about the way my role connects to advisors, you can't understate how important it is for advisors to feel that they are part of a team, committed to clients and doing the right thing for clients, but also committed to leadership in our industry. And I think that's what has drawn so many incredible advisors to Merrill over the course of many decades and day-to-day.

What I want to ensure is that my team and I are stepping up to what that history means, and we're continuing to ensure that this organization feels a certain way, maybe more operationally. We're trying to make sure that this set of capabilities inside Merrill and the broader Bank of America, which is unmatched in our industry, is as accessible and as easy to put to work on behalf of clients as possible. Because for our advisors, that's among the key differentiators for us as an organization, the ability to do just so much for clients.

MD: As you see it today, what do you think advisors of all shapes and sizes value most?

AS: I think that they certainly value capabilities. I mean, all strong advisors, they wake up every day thinking about, ‘how can I do the best job possible for my clients?’ And so that means they need a set of capabilities, a set of tools, whether we're talking about our technology, underlying products, specialists.

Another part of the way I would answer the question though is to ensure that advisors feel that by being part of this team, that they can do more, reach further, dream even more aspirationally about their business than they could anywhere else. Some of that revolves around the hard stuff, products and platforms and tools, but some of it is really driven by more the soft stuff, the culture, the feeling that you're inspired by the people that you're working around, that there's a value to being part of something larger than yourself.

I mean, if we're honest, there's a lot that advisors can do independently. I mean, we see the independent marketplace and the growth that it's had over the years. And if the only analysis is, ‘Do I have an ability to access a piece of technology or transact on behalf of a client?’, you can make a case that an independent advisor can do that just as well as an advisor at Merrill Lynch. Therefore for us to ensure that being part of Merrill Lynch has meaning and value for advisors, we've got to demonstrate that being a part of this larger organization, it brings out your ability to serve clients, grow your business, be an entrepreneur, succeed personally and build a team around you is unmatched by what any other environment has to offer.

MD: One of the things that advisors tell us seem to be most important is the notion of greater freedom and control. And that in this new Merrill, advisors feel like they have less freedom and control than they once did. What do you think about that?

AS: It’s not the first time I've heard it, of course. However, I think at any point in time, it's always easy to look back to a prior era and remember it maybe a little different than it actually unfolded. This business is constantly evolving and client needs are constantly evolving and firm strategies evolve over time. I think that much of what people are talking about when they speak to kind of loss of control, as you put in your question, is not unfamiliar.

If you think back to changes that Merrill's made over the course of decades, in particular, the historic introduction of the CMA (cash management account) in the late 1970s, 1980s, that was seen as a massive loss of control by advisors and the firm introducing into advisor practices things that financial advisors had no interest and felt had no value to them. All that comes from servicing credit card relationships and checking accounts and the like. While clients were embracing CMA and utilizing it, many advisors were complaining day in day out to the then leadership of the firm, that the firm had been destroyed by moving in the direction of bringing banking closer to investing relationships. So first I would apply that lens, which is change is always disorienting and always challenging.

Second, I would say though no one should make any mistake, advisors are the center of the Merrill business. The reason clients are here is largely the strength of the relationship they have with their advisor. This firm moves forward based on the entrepreneurship and the creativity of advisors. There is no firm-wide desire or strategy today, nor has there been at any point in the 30 years I've been part of Merrill Lynch to set out to constrain that entrepreneurial strength and spirit that financial advisors have.

Last thing I would mention, we are in a rapidly changing regulatory environment. At this firm and others, unfortunately, advisors are realizing that the introduction of Reg BI, for example, has real implications in terms of how we serve clients, how we need to supervise our firms, what a fiduciary standard means as opposed to a suitability standard. And so some of it comes from this natural discomfort with change that we all have.

MD: I think a lot of advisors would talk about the fact that a lot of the changes they feel in culture has come from Bank of America coming to town, and that change happened almost 15 years ago. So when you say change is disorienting, what change are you referring to that sort of makes advisors feel like they have less control than they once did?

AS: I don't accept the premise that advisors across the board feel they have less ability to be creative and grow. We've never seen a period where advisors have experienced the kind of growth that Merrill advisors have had in the course of the last 13, 14 years that Merrill's been part of Bank of America. The impact of Bank of America on this business is an advance in terms of our capabilities, putting the reach of a broader organization to work to acquire clients utilizing the balance sheet of Bank of America to do more for clients.

I think a lot of advisors read the change in the regulatory environment, which has happened at the same time Merrill has become part of Bank of America, that somehow Bank of America is the source of change in terms of how we have to supervise the business day-to-day. And I understand it because advisors are seeing and feeling the business through the lens of being part of Merrill Lynch and Bank of America. But when you go and talk to advisors at other firms, as we all do, we're all navigating and experiencing the same change in the operating environment. And I think every advisor at every firm has a list of things they love about their firm and a list of things they think are challenging about the firm that they're part of. But make no mistake, Bank of America has propelled the Merrill Lynch business forward, and it's incumbent upon me and our leadership team and our advisors to take now full advantage of the broader capabilities that have come by virtue of being part of Bank of America.

MD: You had mentioned to me offline that there are three basic things you are most proud of within the Merrill organization: culture, focus on and support for teams and its breadth of platform. What do each of those stand for? And how do each of those things impact Merrill advisors or are considering working for Merrill?

AS: If I think about the most profound changes in the business over the last 30 years, the shift from being a business of individual contributors to a business built around teams may stand out as the most visible monumental change. I mean, 30 years ago, if you were operating as a team in this business, you were a real pioneer. And in some ways there were people snickering that folks who were organized in a team format in those days were almost cheating, finding an easier way to get things done.

Today just about 80% of our advisors are on teams. When you look at people earlier in their career, those numbers are even higher. It's no surprise this is a better way to serve clients. It's a better way for advisors to access and deliver all the resources that we have to offer clients. It also is a structure that lends itself to developing talent. In many ways, this is an apprentice like business.

Our support for teams at Merrill, whether that's visible support in terms of consulting, whether those are economics, the way our team grid essentially provides a boost for the earnings power of advisors who are on teams, all of those are commitments. And we're continuously trying to innovate. I mean, recently we created a program we call our succession planning program, which is an ability for advisors mid-career to move equity from their business to their partner's business within their team. This is really just flexibility in terms of being able to change and restructure a team as needs unfold over time.

When you kind of think about the idea of the thundering herd, the idea that there's real value in terms of being a part of something larger than yourself, one of the ways that becomes real is in peer-to-peer coaching and support. If you talk to people at other firms and they're honest and they have a clear line of sight into this, they would tell you this is very different than what happens at other firms. We've also tried to, without introducing bureaucracy, bring more energy to peer-to-peer development by creating something called our Advisor Growth Network, started as 25 or 30 of our top advisors who were gathered helping me think through what we could do to accelerate the growth of our business four or five years ago. This has now become a network of between 800 and 1,000 advisors who have committed themselves with no tangible benefit to them personally, to helping support the growth among their peers just because they see it as an opportunity to give back to the firm. And they have a confidence that if everyone's skills and if the energy across Merrill Lynch is higher, it's going to reflect well on them.

MD: What about advisors who prefer to practice solo? What kind of support do they get from the firm?

AS: We're not mandating a move to teams, but I think to a certain extent, this is kind of a natural evolution.

We're not going to walk into someone's office and say, ‘It's unacceptable to continue working the way you are.’ But I think we are going to show that there's a lot of power and a lot of potential to do more to accelerate growth, to serve clients better by adopting a team structure.

And not only, I think clients are becoming more and more outspoken as individual contributor advisors are getting to later stages of their careers. They hear from clients directly, ‘Hey, what's going to happen on the day you retire, Mr. or Miss Advisor, who's going to be there for my kids and for my grandkids?’ And one of the things that is a very powerful value that comes from working as an advisor team that's in some cases not as appreciated as it should be, is the ability to have a team with multi-generations in the team face off against a multi-generation family that's a source of great security and confidence in the future. Because the matriarch or patriarch knows that when they're not there and when the senior advisor may have retired, that there's a structure in place that's going to be able to support their family going forward.

MD: The other thing you had mentioned is pride in the breadth of platform. Does it create pressure from your perspective on the part of Bank of America for advisors to sell the bank products, credit lending, mortgage, etc.?

AS: I don't think it's accurate or fair to say that there's "product pressure." There's certainly an expectation that we're going to serve clients fully and that we're going to try to meet client needs as broadly as possible. That's very different. That's rooted in seeing who are our most satisfied clients and what are advisors doing, and what are we as a firm doing to serve those clients? And then how can we ensure that all of our clients have that same level of client satisfaction.

But what flows from that is, for example, a commitment that we should try to have a financial plan in place for most of our clients. And that plan should be refreshed in most cases every couple of years. You don't hear me saying mandate 100%, but that is a platform to understand clients and their needs and their goals, and then ensure that we're serving them very broadly. What's important is nothing that has to do with selling a particular incremental product. What's important is by having this commitment to being the only financial institution that a high net worth or ultra-high net worth client needs, we're putting ourself in position to deliver to clients things that are very valuable to them, to give them time back because this is a much more convenient way to manage their financial life, to give them confidence in the future because they've got a single advisor or advisor team that they're looking to help them navigate all the twists and turns in their life out ahead. It doesn't fall on them to sort of knit the pieces together.

When you're bringing different aspects of your financial life together with a single advisor, you should expect as a client that you're getting better pricing or better terms because you're accessing additional capabilities alongside an existing relationship.

There are a lot of firms that would claim they have the ability to be a one-stop shop. I would argue that most simply can't come anywhere close to meeting their claims, because it's very hard to have the breadth of products and to have the visibility that advisors and clients need across all the aspects of a client relationship and to integrate investment products, banking products, lending products, estate planning relationships, and on and on. It's very hard work. It's very resource intensive. It's a reason that scale is so valuable in wealth management because these aren't a couple million dollar investments. These are hundreds of millions of dollars being invested year after year after year to make it easier and more seamless to serve clients across the board.

Bank of America spends $11 plus billion dollars a year on technology. We are operating today in an organization that has an ability to put resources behind technology development and innovation at a scale that prior generations of Merrill Lynchers could have only dreamed of.

Bank of America acquired Merrill Lynch in January 2009.

MD: How do you compare Merrill Lynch’s all under one roof, fully integrated approach to other models?

AS: Take the independent who says, "I'll help you find the best banking relationship." That has a certain positive ring to it. But when you think about the experience that's being delivered to clients, it's nowhere near the experience that we can offer to have a high net worth client talk to their Merrill team and access the banking capabilities they need through that Merrill team. And therefore, you've got the convenience that comes from the integration, and then you've got the white glove service that comes from a high net worth Merrill team. That's an unmatched proposition.

One of the things clients are frustrated by in the world of consumer banking is they aren't receiving the kind of white glove service that you get from your wealth management organization. And so that's why it's powerful being able to deliver banking through your Merrill team. I'm not going to go firm by firm and draw comparisons, but what I would say, we talked earlier briefly about CMA, Merrill attempted to bring banking capabilities to clients beginning in the late '70s and early '80s. And while it attracted attention and was a powerful innovation, it never fully scaled.

In an average year now, we're opening 150,000 or 200,000 additional checking accounts for Merrill clients every year. Our clients are on the Bank of America mobile app, for example, every day at scale; 80% of our wealth management clients are engaged with us on mobile or online. And one of the reasons that engagement's happening every day is it's about transactional activity that takes place in the banking realm that would've been impossible to achieve if Merrill wasn't connected with the premier consumer bank in the country.

MS: Merrill under your direction has really dramatically grown net new households and assets under management, and the advisor force now stands at about 20,000. What do you think has been the most impactful things you've done to influence such success?

AS: At the core has been the idea of moving growth back to the center of the table in terms of our strategy at Merrill. And we went through some self-reflection six or seven years ago and kind of felt that we had lost that focus on growth. And so by bringing that back and putting that at the core of our strategy, a lot of things kind of flowed from that. We made changes in terms of what we expected our leadership teams to do in the field.

One of the things that we had discovered was in many ways, advisors legitimately felt like their local managers were less empowered and less connected to the success of advisors’ businesses. One fundamental change six years ago was to reset the way we were gauging the performance and paying our managers so that they had skin in the game.

We also very visibly made a change in our compensation framework. The grid is the core of compensation at Merrill Lynch. But we also added to our traditional FA comp program something called the growth grid. As advisors understood the importance of getting the business back on growth footing, the fact that their leaders also had skin in the game around growth, I think that made people be willing to pause and sort of see, "Hey, let's look here over the course of a few years and kind of see how this all plays out."

Over the last five or six years, we've seen just new flows into this business based on client acquisition at unprecedented levels. And when we talk about what responsible growth should look like, organic growth in this business, the best indicator of whether you're getting it done is whether you're bringing in new clients.

There were people who knew this business very well, who were saying, "well, that may be fine for people who are early in their career, new advisors, but to expect growth from senior advisors. That's unwise." Others said, "Hey, are we prioritizing the acquisition of new clients, but turning our back on existing clients? Or if we focus on new households, are we going to bring in a lot of new clients? But we're going to find they're going to be a lot smaller in size than the clients that we serve today." And I'm happy to say that after six years we've discovered or we've proven each of those critiques were wrong. Our senior most advisors are actually growing the most rapidly.

At the same time we saw client acquisition increase, we've seen the client's satisfaction of our existing relationships also rise to all-time highs. And I attribute that to the fact that just the tempo in the business is much higher.

In the fourth quarter 2022, we brought in 8,500 net new households to the firm, at an average size of $1.7 million. That's one of the strongest quarters we've ever seen in terms of new household acquisition. And if you think back 10 years ago, the average new client that we were bringing was not even half that level. So what we've seen actually an increase in terms of the wealth profile of the new clients that have been coming in.

MD: You talk about this interconnectivity between Bank of America and the Merrill Lynch wealth advisors. And a lot of people think about that in terms of referrals from the bank to the advisors. Does every advisor get referrals? How is it determined who gets them and who doesn't?

AS: The lion’s share of advisors are involved in one form or another in referral networks. There are referrals that come from the consumer bank at scale. There are referrals of course, in the high net worth arena that come in the context of investment banking relationships or other institutional relationships. There are access to new clients that come through a presence in the retirement business, whether it's rollovers or other downstream opportunities.

Increasingly, the term referral is becoming a little bit archaic. You want to have the working relationships between Merrill Lynch advisors and the rest of the company get closer and closer over time, so that relationships and opportunities passing from Merrill to the broader bank or the broader bank to Merrill just feel like coordinated client coverage, not something that the word referral conjures up, which on a bad day can feel like tossing an opportunity kind of over the fence to another side of the company.

MS: Now when a lot of advisors talk about Merrill Lynch, they talk about Mother Merrill being overbearing and bureaucratic, and they credit the bank for having made that change. What you would say to those advisors that feel that? And how do you think about managing the delicate balance between the desire to listen to advisors and give them what they want and manage the needs of the organization as a whole?

AS: I think there is much, much, much more that is the same than is different in terms of what it feels like to be part of Merrill Lynch. At any given point over the last 30 years, there's always 5% or 10% of things that the firm is doing which is frustrating to advisors. And one of the great strengths of Merrill Lynch over long periods of time has been the commitment to take that feedback from advisors and put it to work. I try to make sure that we as a leadership team are connected to advisors in the right way so that the feedback is coming in and that we're certainly aware of what are the 5% or 10% of topics that need to be addressed in the moment.

It's a dynamic which has always been in our business and other businesses where, things are challenging, the market is changing, client needs are changing and organizations have to adapt to it. And there's friction.

MD: Do you think that growth and growth of an advisor's business, the ability to make more money to serve clients well necessarily is equivalent to being happy or content? How do you think about the connection between contentment and happiness and changes in culture and the attrition and why big teams are leaving?

AS: The competitive attrition rate on average over the last five years has been just about 4%. If we go back to the years immediately after the acquisition of Merrill by Bank of America, attrition rates were far higher. And if we go back to prior to 2008, I think competitive attrition rates were probably closer to 2.5% or 3%.

There is a tremendous focus on how attractive the wealth management marketplace is. And it has brought lots of focus, lots of capital, and created a war for talent in wealth management. And unsurprisingly, Merrill Lynch as the premier brand in wealth management with an advisor force that tops Barron's list, Forbes’ lists, and many others, we get more than our fair share of incoming calls from recruiters and others.

I hate seeing any advisor leave Merrill Lynch full stop. I want our team to thrive and to grow. I want everyone to be commercially successful and contented and to feel like there's an ability to serve clients here like you can nowhere else.

So when anyone leaves, it hurts. I think that that war for talent means there's a bid that is very attractive, that at different points in people's lives, based on factors that are pretty far-field from their client business to something that's happening in their own life that causes the need or the desire for change. There's not a lot that we can do about that. What we can do is try to put in place the most advisor-centered and positive support for advisors across the lifecycle that exists anywhere in the industry. And by that, I mean best in class training program, most growth oriented set of programs and products and services while advisors are in the core, a period of their career serving clients and hopefully thriving. And then a very attractive and compelling program at the end of advisors’ careers to transition their business, monetize their business, and ensure clients and colleagues are being well treated through the transition.

I know that the advisors that I know at Merrill Lynch and elsewhere, where they get satisfaction is doing an awesome job for their clients and seeing the impact of that work, doing a great job in terms of supporting colleagues and ensuring that their colleagues are growing and developing, playing a role in their communities and seeing opportunities for the success that they have achieved to kind of flow back to the causes and groups that they care about in their local communities.

MS: I'm not sure that I agree that when a big team leaves, it's because there is a transitory problem, some operational problem, something that's not working. From where I sit when a big team leaves, it's a combination of two things: One, they're drawn to another model. But it's also equally in most cases when a big team leaves that there are pain points, some sort of a philosophical disconnect with the firm. What do you think about that?

AS: I think very broadly, people leave firms for lots of different reasons, and some of them are anchored in legitimate business strategy concerns. Hey, if I was a Merrill advisor over the years and I had a large institutional investment business serving public fund clients, we were very clear that this was not going to be the right firm for you because we had well-founded concerns about serving public sector entities from an investment management perspective, and we tightened that area of our business down substantially.

I think that scenario is a small percentage of the people who leave. And I say that because over half of the people who left Merrill Lynch last year were individuals who had come to Merrill on a recruiting deal nine or 10 years earlier. I'm not saying anything about that is untoward, but I think what that says is, this is an advisor who's made a decision that over the course of their career, they're going to move firm to firm. And that is a part of their personal strategy for maximizing their success over the course of their career.

We see a third set of advisors who have maybe not a difference of opinions strategically around the attractiveness of a segment, but they may have a different view around what business practices are acceptable in the current regulatory environment. And in some cases, these are tricky situations where something may be on the radar screen of the firm, the local supervisors, and caused an advisor to feel that the firm's holding the supervisory reigns pretty tight.

I would strongly make the case that great advisors are not leaving here because they feel that something's happened to change the course of this platform or franchise or limit the potential for their success in a way that's rooted in a strategy change at Merrill or the impact of the broader bank. I think it's just the opposite interestingly. I'll give you a factoid. When Merrill Lynch was acquired by Bank of America, I think there were four or five financial advisors at Merrill Lynch who did more than $5 million in gross commissions. But that number last year was over $250 million. And we are as an organization, applauding that growth every day and doing all we can to reinforce it and ensure that we're building on that momentum going forward.

MS: You were quoted some time ago saying that you viewed aggressive deals as a pointless expense because many advisors just turn around and leave in 10 years for another deal. But it was reported at the end of '22 that Merrill is back in full force in veteran recruiting offering competitive deals. What changed your mind and what is your stance on recruiting today?

AS: We've got to focus here on driving and delivering 3%, 4% per year net growth in our advisor force over the balance of the decade, and we're focused on doing that, not largely based on experienced advisor recruiting. That's part of the story.

But our growth strategy is really founded four pathways into the firm. One is our core advisor training program—the Advisor Development Program. We really reset it during the pandemic so that there's a pathway for people who are just out of college new to the industry, in most cases, come in and spend time initially in our mass affluent business, the Merrill Edge business, learn the foundational skills to be an advisor there, and then transition to become a Merrill Financial Solutions advisor, which is essentially a trainee role at Merrill. That program has more than a thousand people in it now. And we're looking to see about a thousand advisors a year graduate from that program.

Second pathway, I used the word earlier on the podcast, apprentice. This is an apprenticeship business, and we've got a lot of opportunities within teams for people to move from client support roles to advisor roles. We call it our team financial advisor. That's 250, 300 new advisors per year for us.

As we got these two programs up and moving over the last months or two years, we've also then felt we were in position to do more recruiting. And our initial focus was advisors early in their career at other firms who we thought if they joined Merrill would have the potential to increase their success as an advisor, maybe move their practice more to the high net worth and ultra-high net worth market in many cases to join an existing Merrill team. And we call this our Accelerated Growth Program. Basically, we're looking to bring people in on a salary plus grid based compensation plan, with the salary expiring after three, four years, bring them into the firm and see if we could put them onto a stronger growth path as an advisor through this AGP program. Last year, we hired almost 300 advisors through the AGP program. That's our strongest year in recruiting in over a decade.

With the fourth pathway, we are back looking to add some experienced advisors. And we had really closed that down five or six years ago, because we wanted to ensure that we were focused on organic growth. We've done that well despite the market environment of '22 and the impact of the pandemic in 2020 and 2021. We have an offer that I think is consistent with the market, but we see some deals that take defy any rational economic analysis in terms of them being accretive to the acquiring firm. We just had some advisors who unfortunately left us in the northeast, and the reported deal that they took was above a 400%. We've seen what the transition experience has been for their clients and six months in less than 50% of the clients have moved. When you put all that together and kind of assess what that would look like in terms of an economic proposition for the acquiring firm, that's not good. We're focused on bringing some experienced teams over, but we're also going to ensure that we're doing it in a way that is client friendly, shareholder friendly, and good for the advisors who make the move.

MS: What do you think Merrill looks like five or 10 years from now?

AS: When we talk about modern Merrill, there are really three ideas. One is the idea we touched on earlier, being a one-stop shop for high net worth and ultra-high net worth clients. And so 10 years from now, you'd expect to see even more seamless integration of the broader products and services. If I open up my Merrill app on my phone or my Bank of America app, I can see all aspects of my financial relationships here all brought together. We're investing hundreds of millions of dollars a year to continuously improve that experience. I would expect us to feel even more integrated, even more seamless, more intuitive to clients.

Second, to see our technology prowess be recognized by clients, it's not the same as the power of the relationships that clients have with their advisors, but it’s another very powerful reason to be doing business here versus somewhere else. That this is a firm that is both high touch as we've always been, but also high tech, and then 10 years from now expect to see much more in the way of diversity across our advisor force.

You had asked earlier, "If you could close your eyes and wish for kind of one dream to come true, what would it be?" For me that dream would be a lot more diversity among our advisor force. I'd like to see 50% of our advisors be women, because more than 50% of our clients are women today. And I feel that's a place where Merrill Lynch and in the whole industry has a lot of ground to cover very, very quickly.

MS: Andy, will there be an independent channel within Merrill Lynch 10 years from now?

AS: I don't think so, predominantly because I don't think it will or would serve a need. It's something that we've looked at every couple years for 30 years. We always felt that we wouldn't have an ability to support those advisors in the same way that we support Merrill advisors. That's not only a topic that revolves around products and services and platforms, and comp, it revolves around culture, the idea of one unified Merrill Lynch organization out in the world.

MD: What's your morning routine?

AS: It's up at 5:15 generally on the way to the office by 6:00. I get here around 7:00, absorb the news that I can in 45 minutes or so. And then a series of meetings that get rolling usually around 8:00, and there's normally a good amount of watching CNBC or listening to it at least on the drive to work in the morning.

MD: What's the toughest decision you've ever had to make?

AS: Over the last 20 years, having the balance of what does an organization need from a senior manager, senior leaders, are people in position able to deliver what the firm needs and what our advisors and clients need. Weighing that off with loyalty, longstanding relationships, and then having to make decisions around when change is needed. Those are always really, really hard. And when change happens and you look back generally you feel that the difficulty of those decisions caused you to weigh them probably longer than you should have. But nevertheless, I think those are usually the tough decisions alongside people decisions. See, choices end up generally being easier, and they're frequently decisions that are two-way door decisions that you can kind of make a decision test and learn a little bit, and then redirect if things aren't working out. People decisions—those are very different because as I said, those are long-standing relationships, people's lives, their families that are involved alongside what's right for the firm.