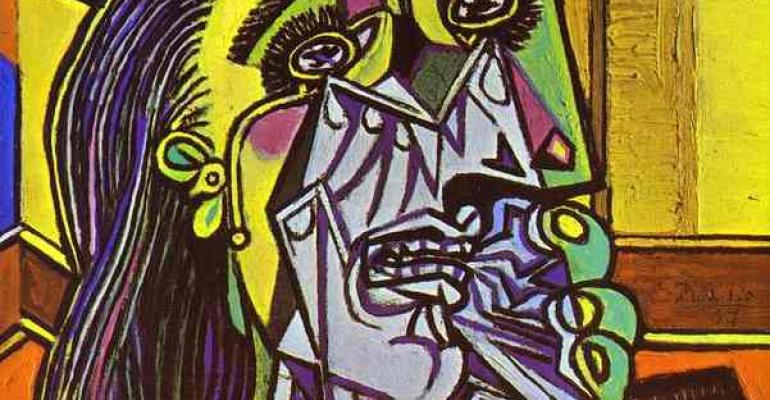

What’s the fair market value (FMV) of a deceased collector’s undivided fractional interest in 64 works of art—art that includes pieces by Pablo Picasso, Henry Moore, Jackson Pollock, Paul Cezanne, Jasper Johns, Ellsworth Kelly, Cy Twombly, Robert Motherwell, Sam Francis and David Hockney? Such was the daunting question facing the Tax Court in Estate of James A. Elkins, Jr. deceased, et al. v. Commissioner, 140 T.C. No. 5 (March 11, 2013).

Quite a Collection

Decedent James A. Elkins, Jr. and his wife Margaret collected contemporary art between 1970 and 1999. They displayed their collection primarily in their Houston home and family office. A few pieces were displayed at other locations, but none of the 64 paintings were ever sold. Because the art was purchased during the Elkins’ marriage, the art became community property under Texas law.

On July 13, 1990, James and Margaret each created a grantor retained income trust (GRIT)) funded by each spouse’s undivided 50 percent interest in a large Henry Moore sculpture, a Picasso drawing and a Pollock painting (the GRIT art). Each GRIT was for a 10-year period, during which each spouse retained the use of the transferred interests. After 10 years was up, each spouse’s interest was to pass to the three children. Thus, after 10 years, the children would have 100 percent ownership of the GRIT art, with each child possessing a one-third interest.

Margaret died in 1999, prior to the expiration of her GRIT, and her 50 percent undivided interest in the GRIT art passed to James. James survived the 10-year term of the GRIT, so his original 50 percent undivided interests in the GRIT art passed to his three children in equal shares (16.67 percent each). James retained the 50 percent interest he received from Margaret, and that interest became part of his gross estate.

James and his three children executed a lease agreement, effective July 13, 2000, for the Picasso drawing and the Pollock painting. The children leased their combined 50 percent interest to James, so that he could retain year-round possession of the two artworks. The lease contained automatic extensions, unless James decided to opt out (which he never did). Under the lease terms, James and his children agreed not to sell their respective percentage interests in any of the artwork during the initial or additional terms without the joinder of the parties. The parties left blank the rent due under the lease until May 16, 2006, when Deloitte LLP determined an appropriate monthly amount for the two art pieces. Deloitte determined that from July 13, 2000, through the valuation date, $841,688 was the amount of rent due. James’ estate sought to deduct payment of that rent amount to James’ children. On audit, the parties agreed to reduce the amount of that deduction to $10,000, the propriety of which wasn’t at issue in the case.

Disclaimed Art

Under the terms of Margaret’s will, her 50 percent community property interests in the other 61 pieces of art passed outright to James. However, James disclaimed a portion of those interests equal to his unused unified credit against estate tax available to Margaret’s estate. By doing so, the disclaimed portion could pass to James’ children free of estate tax. Relying on appraisals obtained by Margaret’s estate, James disclaimed a 26.945 percent interest in each of the 61 artworks (the disclaimed art). Pursuant to Margaret’s will, those fractional interests passed in one-third shares to each of the children, resulting in each child receiving an 8.98167 percent interest in each item of disclaimed art. The balance, a 23.055 percent interest in each item, passed to James. Added to his 50 percent interest in each item of disclaimed art, James retained in total a 73.055 percent interest in each item of disclaimed art.

In February 2000, shortly after James executed his partial disclaimer, he and his three children entered into a “cotenants’ agreement” relating to the disclaimed art. Among other provisions, the cotenants’ agreement provided that each cotenant is entitled to possession and control of each item during a one-year period, equal to the percentage interest in each such item, multiplied by the number of days in such year. The parties also agreed, among other things, to pay for the transport of each item and to maintain/restore each item. Moreover, the parties agreed that any item may only be sold with the unanimous consent of all of the co-tenants; the net sale proceeds would be payable to each party in accordance with their respective percentage interests in the property. The parties agreed that the cotenants’ agreement would be binding on their heirs and representatives and governed under Texas law.

After James’ GRIT terminated in July 2000, the parties to the cotenants’ agreement amended it to include the Moore sculpture, which was one of the art pieces covered in the GRIT but not included in the July 2000 art lease. On Feb. 17, 2006, the children signed the amended cotenants’ agreement for themselves and on behalf of their father (under a prior power of attorney form).

James’ Will and Estate Tax Return

James’ will provided that his children would inherit his personal and household effects, including his undivided fractional ownership interests in the art. His residuary estate passed to a foundation (the Elkins Foundation), which entitled his estate to a charitable deduction under Internal Revenue Code Section 2055. All estate taxes, interest and penalties due from James’ death were to be charged against James’ residuary estate, reducing the distribution to the Elkins Foundation and thus reducing any corresponding charitable deduction.

James’ estate timely filed a Form 706 on May 21, 2007, reporting a federal estate tax liability of $102,332, 524. The estate also filed a Schedule F that included James’ 73.055 percent interests in the 61 works of disclaimed art subject to the original cotenants’ agreement, valued at $9,497,650 and his 50 percent interests in the three pieces of GRIT art (the Picasso drawing and Pollack painting remained subject to the art lease on the valuation date), valued at $2.652 million. The estate derived at these values by determining James’ pro rata share of the FMV of the artworks as determined by Sotheby’s Inc. and then applying a 44.75 percent combined fractional interest discount for lack of control and marketability, as determined by Deloitte, to those pro rata share amounts. The estate and the Internal Revenue Service stipulated a total undiscounted FMV of $24,580,650 for the disclaimed art and $10.6 million for the GRIT art.

IRS Says “Pay Up”

The IRS determined that James’ gross estate included his 73.055 percent interests in the disclaimed art, at an undiscounted FMV of $18,488,504, and his 50 percent interest in the GRIT art, at an undiscounted FMV of $5.3 million. As an alternative basis for using the undiscounted values of James’ fractional interests in the art, the IRS argued that the restrictions on the art subject to the cotenants’ agreement and the fractional interests in the art subject to the art lease were “an option…to use such artwork at a price less than fair market value” and “ a restriction on the right to sell or use” the interest in the artwork so that pursuant to IRC Section 2703(a)(1) and (2), James’ interests should be valued without regard to those restrictions. The IRS further claimed that the discounts used in determining the FMV of James’ fractional interests in the artwork were overstated and a discount was inappropriate. Finally, the IRS argued that because James’ will provided that estate taxes should be paid out of the residuary estate passing to the Elkins Foundation, the deduction for the charitable bequest to the foundation by the amount of the additional estate tax payable, should be reduced.

James’ Estate Says “No Way”

James’ estate timely filed a petition, assigning error to the IRS’ deficiency, seeking a refund of estate tax based on the estate’s 1) overvaluation of the art, 2) entitlement to a greater charitable contribution deduction than claimed, and 3) entitlement to deductions for attorney, accountant, appraisal and administration fees.

Expert Nash Speaks

To support its proposed discounts in valuing James’ fractional interests in the art, the estate offered the testimony of three experts. David Nash, the estate’s first expert, was accepted by the court as an expert in the art market, the marketability of art and art valuation. Before his valuation report, Nash viewed each of the 64 pieces, met with James’ three children and was asked to assess the marketability of James’ interest in each work. He believed that any potential buyer would have to take into account that the children (whom Nash called “shareholders”) are “committed to retaining the art in the family until the last shareholder dies.” Nash determined that potential buyers of the pieces would demand steep discounts from the pro rate FMV for James’ fractional interests; noted that auction houses don’t sell fractional interests in art; and believed that a collector would be “put off by the uncertainty of his ever being able to acquire the whole work.” He also noted that it would be highly unlikely that a museum would pay “anything close” to the pro rata value of the fractional share, when it would never know if or when it could obtain full control of the pieces. Noting, however, that although it’s common for two museums to jointly buy a work of art and rotate exhibiting the pieces in proportion to their interests, Nash concluded that in this instance, museums wouldn’t be interested in buying joint interests when the co-owners were James’ children (rather than another museum) and would face potential litigation to force a sale of the art. Finally, Nash concluded that art dealers, investors and funds would similarly have little interest in buying the fractional interests, due to the logistical difficulties surrounding the ownership of the pieces.

Nevertheless, Nash did acknowledge that spectators would be willing to buy James’ interests if appropriately discounted. To determine the FMV of James’ fractional interests in each of the 64 pieces, he categorized the pieces into three groups. Category I consisted of five pieces that were “highly desirable” and included a Jasper Johns piece that he valued at $8 million and a Robert Motherwell piece that he valued at $1.5 million. Nash’s discounts from the pro rata FMV of James’ interests in Category I pieces were between 50 percent and 80 percent. Category II contained 19 pieces for which “alternate choices could be found and purchased outright.” Nash considered these pieces as good examples, but “not masterpieces” by the artists. He concluded that a potential buyer would demand a discount of about 80 percent to 90 percent of the pro rata value. The 40 pieces in Category III were “not worth the risk at any level” and a potential buyer would demand a discount of about 95 percent. As such, the interests in Category III pieces had only a nominal value. Thus, Nash determined the discounted FMV of James’ interests in the art as Category I, $4,336,859; Category II, $976,451; and Category III, $149,056, for a total of $5,462,66.

Experts Miller and Mitchell Speak

The Tax Court accepted the estate’s second expert, William T. Miller, as an expert on the nature, procedure, time and cost of partition actions. Miller stated that partition is prohibited under the terms of the cotenants’ agreement, but it could proceed through an adversarial partition action that would culminate in a private or public sale of the work of art. He estimated that a buyer of James’ fractional interest in any of the more expensive pieces would have $650,000 in legal and receiver fees. Thus, he reduced the FMV of pieces, between $250,000 and $650,000 to $250,000. For the remaining pieces, he assumed fees equal to the pro rata value of each piece and assumed additional costs for sales commissions, appraisals, crating, moving, insurance, storage and auction house fees. Thus, for a hypothetical buyer, Miller determined that the total costs for legal fees and other expenditures could range from $25,000 to over $1 million (for the Jasper Johns piece) from trial through appeal.

The estate’s third expert, Mark L. Mitchell, proffered his opinion as a director of valuation services at Clothier & Head in Seattle. Mitchell derived his opinions based on Nash’s report on the FMV of the 64 pieces and on Miller’s report regarding partitioning rights and costs relating to partition. He also analyzed the economics of the art market and used a quantitative approach to reach his conclusions. Mitchell noted the limitations imposed by both the cotenants’ agreement; the nature of fractional interests; the need for expensive partitioning processes before any sale; the limited use of the art as collateral; and a limited market for such interests, and concluded that substantial discounts were warranted. As such, he described two options for a holder of an undivided interest in art to monetize his holding: Option 1, which would be a sale of the undivided interest, and Option 2, which would be a successful partition ultimately leading to a sale of the work and pro rata distribution of proceeds among all the interest holders. Under Option 1, both the holder and buyer would consider several adverse factors in arriving at a price for the undivided interests (including limited possession of the art, transportation costs, insurance, etc.). Moreover, under this option, the buyer would risk ending up with a non-marketable interest, since the other interest holders have no desire to sell. Under Option 2, to make the investment worthwhile for the buyer, the discount must exceed the cost of anticipated partition litigation. A buyer under Option 2 is, in essence, purchasing a “litigation claim.”

Thus, Mitchell determined that a buyer under Option 1 would expect a nominal financial return for art in general of 6 percent plus, in this case, an additional 8 percent consumption return. Mitchell then added a 2 percent rate of return for impaired marketability and other risk factors, resulting in a total 16 percent rate of return. He then modified the 16 percent overall rate of return to account for the varying quality of the pieces. Adopting Nash’s three categories, Mitchell concluded an overall 14 percent required rate of return for pieces by Pollock and Moore and 18 percent required rate of return for the other three Category I pieces. With those rates of return, he arrived at a 51.7 percent discount from pro rata FMV for James’ s interests in the Pollock and Moore pieces, a 65.8 percent discount for James’s interests in the Francis and Motherwell pieces and a 71.7 percent discount for James’ interests in the Johns piece. For James’ interests in the 19 Category II pieces, Mitchell determined a 71.1 percent discount from pro rata FMV. For Category III pieces, Mitchell arrived at a 79.7 percent discount from pro rata FMV.

Mitchell computed the discounts under Option 2 as follows: For James’ interests in Category I pieces and five of the Category II pieces, discounts ranging from 60 percent to 85 percent; for James’ interests in the remaining Category II pieces, a discount of 90 percent or more; and for James’ interests in all Category III works, a 100 percent discount, on the theory that the costs of litigation would exceed the sale price of all Category III works.

Mitchell chose the lesser of the Option 1 versus Option 2 discounts as the appropriate discounts for James’ interest in each work of art and determined the discounted FMV as follows: Category I, $5,150,420; Category II, 1,904,117; and Category III, $604,108, for a total of $7,658,645. Although Mitchell’s total exceeded the discounted FMV computed by Nash, it was still much less than the $12,149,650 total discounted value for James’ interests in the art reported on Schedule F of his estate tax return. It’s the difference between $12,149,650 and Mitchell's discounted total FMV that constitutes the basis for the bulk of the estate’s claim for refund, the balance being attributable to the increase in the charitable contribution deduction arising by virtue of the refund relating to the estate's alleged overvaluation of the art on its return.

Experts Hanus-McManus and Cahill Speak

The IRS offered the opinion of two experts. The court accepted the IRS’ first expert, Karen Hanus-McManus, as an appraiser of modern and contemporary art. She testified that there’s no established marketplace, both in the primary and secondary market, for the sale of a partial interest in a work of art.

The Tax Court then accepted the IRS’ second witness, attorney John R. Cahill, as an expert in art transactions. Relying on case law and his own observations of museum-related and commercial transactions involving joint ownership of art, Cahill concluded that, “the Sale Restriction and related terms in the Cotenant's Agreement, Amendment to Cotenants Agreement and Art Lease are not comparable to similar arrangements entered into by persons in arms length art market transactions.”

Each Side Makes Its Case

The court was faced with the challenge of whether to reduce the total value of James’ interests ($12,149,650) included in his gross estate and reported on his estate tax return to $7,658,645. The parties had stipulated that the total, undiscounted FMV of the art on the valuation date was $35,180,650 ($24,580,650 for the disclaimer art and $10,600,000 for the GRIT art), and the IRS issued a deficiency based on its opinion that the undiscounted value, to the extent it’s allocable pro rata to James’ interest in each of the 64 pieces of art (totaling $23,257,3939) constitutes the value of James’ interests in the art for federal estate tax purposes.

The IRS argued that there should be no discount of the pro rata FMV of James’ interest in each of the 64 pieces of art. First, the IRS stated that the restrictions on sale in the cotenants' agreement and the art lease are restrictions that must be disregarded under IRC Section 2703(a)(2). Second, because the proper market in which to determine the FMV of fractional interests in pieces of art is the retail market in which the entire work (consisting of all fractional interests) is commonly sold at full FMV, a fractional interest holder (being entitled to a pro rata share of the sale proceeds) isn’t entitled to any discount for his interest.

The estate argued that IRC Section 2703(a)(2) doesn’t apply to the cotenants' agreement because Paragraph 7 of the cotenants’ agreement restricts only the sale of any of the 62 works of art covered by the agreement (cotenant art). It doesn’t restrict the sale of a cotenant's or co-owner's fractional interest in the work, and it’s James’ fractional interests in the cotenant art, not the art itself, that must be valued for federal estate tax purposes. The court noted that the estate, however, didn’t oppose the application of Section 2703(a)(2) to the two works of GRIT art subject to the art lease; that is, the estate didn’t argue that the restriction on sale provision in the art lease gave rise to a discounted value for those two works. The court thus interpreted the estate’s silence in this regard as an admission that, pursuant to Section 2703(a)(2), it must value James’ interests in the leased art without regard to the restriction on sale provision in Section 10 of the art lease.

The Court Weighs In

The court noted that IRC Section 2703(a)(2) doesn’t refer to intent as a controlling or even relevant factor; thus, the only question is whether the property to be valued, for estate or gift tax purposes, is subject to a restriction on sale or use. According to the court, whether Paragraph 7 of the cotenants' agreement was a restriction on James’ right to sell the cotenant art or was a restriction on his right to use the cotenant art wasn’t important. What was important, said the court, was that pursuant to Paragraph 7 of the cotenants' agreement, James, in effect, waived his right to institute a partition action, and, in so doing, he gave up an important use of his fractional interests in the cotenant art. Thus, Section 2703(a)(2) was applicable to the restriction in Paragraph 7 of the cotenants' agreement, on sales of cotenant art.

The court’s conclusion that Section 2703(a)(2) negated the restriction on sales of cotenant art in Paragraph 7 of the cotenants' agreement left a hypothetical willing seller and buyer in the same negotiating position with respect to James’ interests in all 64 works of art. The court’s next task, therefore, was to determine whether any discounts were permissible, on each of the 64 pieces. The IRS argued that that no discount was appropriate for two reasons: 1) under Estate Tax Regulations Section 20.2031(b), the FMV of tangible personal property must be determined with reference to the market in which the property is most commonly sold to the public, and 2) in the case of art, that market is the retail market in which all fractional interest holders agree to sell (or sell after a partition action) the underlying art (that is, the art is sold for its undiscounted FMV, after which each fractional interest holder receives his pro rata share of the proceeds). The IRS also cited case law to support its position.

The court reviewed the “unchallenged facts” that demonstrated that James’ three children had “strong sentimental and emotional ties to each of the 64 works of art” so that they treated the art as "part of the family." Those facts “strongly suggested” that a hypothetical buyer of James’ fractional interests in the art would be confronted by co-owners who were resistant to any sale of the art, in whole or in part, to a new owner. In fact, James’ children specifically communicated this position to expert Nash. Given the children’s resistance, a hypothetical seller and buyer necessarily would be faced with uncertainties regarding the latter's ability to monetize his investment in the art. Thus, some discount was appropriate to allow for these uncertainties.

The court rejected the IRS’ interpretation of Estate Tax Regs. Section 20.2031-1(b) as mandating reference to the retail market for entire works of art in determining the FMV of James’ fractional interests in the art. The court noted that experts Nash and Hanus-McManus agreed that there’s no market (retail or otherwise) in which undivided fractional interests in art are "commonly sold to the public." Furthermore, the prospect of an FMV sale of the art followed by a pro rata division of the proceeds among the co-owners is extremely uncertain. Although there existed a retail market for works of art with multiple owners, that didn’t mean that all fractional interests in art must be valued as if it’s certain that the art will be sold in that market. “The regulation should not be read in a vacuum, without reference to actual circumstances,” said the court, citing prior Tax Court decisions. Moreover, the court’s view was that the IRS ignores precedent and the willingness of courts in other cases to permit discounts for fractional interests in art, provided there’s adequate proof of entitlement. And, the court also rejected the IRS’ argument that partition costs may be deductible as administration expenses under IRC Section 2053(a)(2), but may not be cited as a justification for a valuation discount. Finally, the court found the IRS’ reliance on revenue rulings unpersuasive to deny any discounts. “There is no bar, as a matter of law, to an appropriate discount from pro rata fair market value in valuing, for estate tax purposes, decedent's undivided fractional interests in the art,” the court concluded.

And the Discounts Are…

So, what’s the extent to which the estate is entitled to discount the pro rata FMV of James’ interests in the art?

According to the court, expert Nash's analysis and (derivatively) Mitchell's analysis were flawed because they failed to consider not only the children's opposition to selling any of the art, but also the children’s ownership position vis-à-vis that of the hypothetical willing buyer and the impact that the ownership split would have had on the negotiations between seller and buyer. Both experts should have recognized that the children, cumulatively, were entitled to possess 61 pieces of co-tenant art for a little over three months each year and entitled to possess the three pieces of GRIT art for six months of each year. The brief period of annual possession, the expense and the inconvenience of annually moving the art from the hypothetical buyer's premises back to Houston most likely would have caused the children to reassess their professed desire to hold on, at all costs, to their ownership status quo existing after their father’s death. According to the court, a hypothetical buyer would be “in an excellent position to persuade the Elkins children, who, together, had the financial wherewithal to do so, to buy the buyer's interest in any or all of the works, thereby enabling them to continue to maintain absolute ownership and possession of the art.” In fact, one of James’ children testified that the strong desire to retain possession of the art in place would motivate the children to purchase the hypothetical buyer's interests, most likely in each case for an amount equal or close to the undiscounted FMV of the interest. “It defies logic,” said the court, “to assume that, as 27% or 50% owners and possessors of the art, the Elkins children would spend millions of dollars to retain their status as such, perhaps as defendants in multiple partition actions that could drag on for many years, when they would be able to acquire 100% ownership and possession of the art, which, after all, is what they really want.” The estate, however, argued that the price the children would pay wouldn’t exceed FMV, but the court wasn’t convinced:

[T]the Elkins children would be willing to purchase the hypothetical buyer's interests in the art at a much higher prices than a disinterested buyer would be willing to pay for the same interests because of the children's added motivation of keeping the art within the family as, in petitioners' words, ‘a memorial to their parents rather than [as] an investment.’

Thus, the court considered “the actual bargaining position that a hypothetical buyer of James’ interests in the art would have vis-à-vis the interests of the Elkins children” was relevant. The court also pointed to cases that recognized that certain properties possess an “assemblage value,” in this case, that the children would pay a hypothetical buyer of James’ interests in the art more than a disinterested collector. And, that hypothetical buyer could be satisfied to have the pieces for 7.055 percent (or 50 percent) of each year. As such, the court found that the estate’s experts were incorrect in assuming that James’ children would fight to maintain the status quo. In fact, the court found that the experts ignored the “high probability” that James’ children would want to buy the hypothetical buyer’s interest in the pieces. Thus, Mitchell’s discounted values for the pieces were “unrealistically low.” The court furthermore rejected the estate’s argument that James’ children would spend any amount necessary to keep their minority (or 50 percent) interests in the pieces, finding that the children would most likely be willing to spend even more to obtain their father’s fractional interests and keep for themselves 100 percent ownership and possession of the pieces.

The court thus concluded that a hypothetical willing buyer and seller of James’ interests would agree at a value at or fairly close to the pro rata FMV of those interests. However, a nominal discount of 10 percent from full pro rata FMV was appropriate to compensate for the uncertainty regarding James’ children’s intentions.

And that 10 percent, said the court, was all the discount the estate was entitled to.