When Vanguard Founder Jack Bogle introduced the first index fund to the American public in the 1970s, he wasn’t promising that it’d outperform the markets. Rather, the promise behind index funds was to diversify across and track the performance of the overall market at a low cost to the investor. Today, you can invest in the Vanguard 500 Index Fund for as low as 4 basis points.

But some legacy index funds—which track the exact same index—charge much, much higher fees than that, and investment gurus say they are simply unjustifiable.

Such high-fee index funds are relics of a time when investors didn’t bat an eyelash at their expense ratios—or more likely didn’t know to ask and weren't explicitly told. Most of these index-mirroring funds are Class C shares that get most of their deadly annual price tag from 12b-1 fees, most always levied at the maximum allowable 1 percent. Much of those “marketing and distribution” fees go to providing brokers with their trailing 12-month commissions. This remains a dark and increasingly archaic corner of the financial services world, yet many investors still live there either due to broker inertia or “set it and forget it” retirement programs.

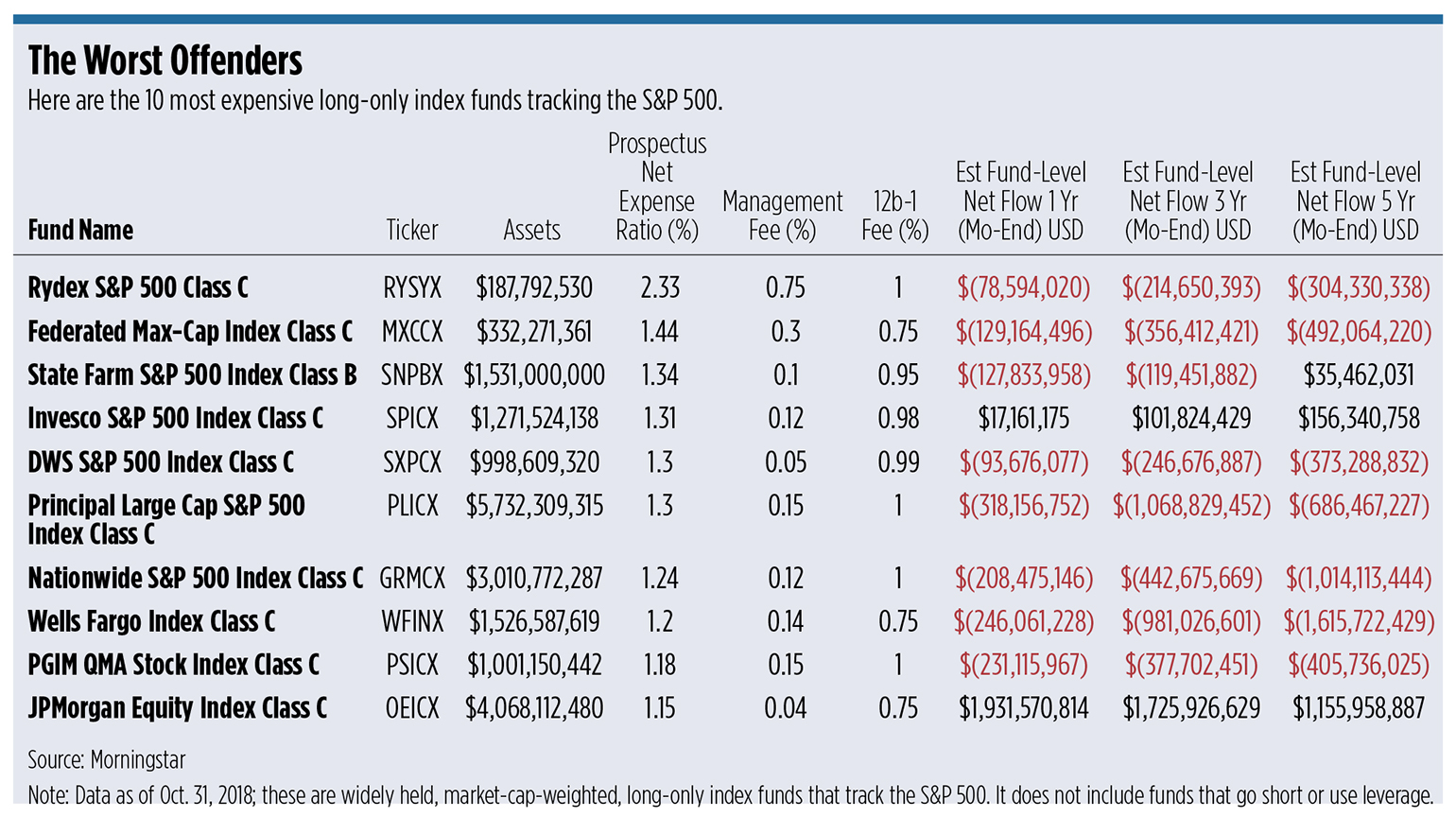

The Rydex S&P 500 Index Fund—often considered the poster child of high-fee index funds—charges a net expense ratio of 2.33 percent. That includes a management fee of 75 basis points and 1 percent 12b-1 fee, a reward to the advisor for selling the fund. But there are more than a dozen similar, plain vanilla funds—also tracking the S&P—with net expense ratios over 1 percent. Federated Investors, State Farm and Invesco are just a few providers.

Defenders of 12b-1 fees say the trailing commissions are meant to compensate the advisor for providing advice to the client that bought the fund; the client's costs would be the same in a fee-based account. But that argument is increasingly dubious, industry watchers say, as the gap between what these funds charge and low-cost alternatives is widening. State Street now charges 2 basis points for its Equity 500 Index Fund. Fidelity recently introduced index funds with zero expense ratios.

“Where we stand today, there’s no excuse that anyone should have to pay fees that are just downright egregious for exposure to mainstream indexes, exposures that can be had for next to nothing if not, in a small handful of cases, nothing in specific channels,” said Ben Johnson, director of global exchange traded fund and passive strategies research at Morningstar.

Despite the prevalence of low-cost options, many investors are still in these funds. According to an analysis by Morningstar, the top 20 most expensive S&P 500 index funds had $57 billion in assets combined. The State Farm S&P 500 Index Fund, for instance, with a net expense ratio of 1.34 percent, has more than $1.5 billion in assets.

“For the time being, there are some unfortunate souls out there paying many, many multiples of what can even be considered borderline reasonable for index exposure,” Johnson said.

Advisors are largely to blame for their persistence. Scott MacKillop, CEO of First Ascent Asset Management, a turnkey asset management platform, says these funds tended to be sold by the larger brokerages, where a broker is incentivized to sell them.

“It’s not really an indictment of investors, per se, because I think somewhere along the line they trusted a broker or an advisor to advise them on the purchase of the funds that they have,” MacKillop said. “But they clearly aren’t doing any due diligence on their own, or they would know that they could very easily go get a different fund.”

Many advisors likely put their clients’ portfolios in these funds years ago, where they remain out of sheer advisor inertia. And unless the investor is proactively doing the due diligence themselves, they’re stuck.

“Once the investor buys the high-fee index fund, a financial advisor may not move the assets away even if the account moves to an asset-based fee model,” said Benjamin Edwards, associate professor of law at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. “One reason for this is that the advisor might be hesitant to criticize his or her own work. Pointing out that the fees are too high tends to raise questions about why it was recommended in the first place.”

“The easy way out is to pick a mutual fund, leave it in there forever, and don’t see if there’s better alternatives or see if anything has changed,” said Todd Rosenbluth, director of ETF and mutual fund research at CFRA. “Even an index-based strategy warrants ongoing due diligence.

“This is setting it and ignoring it. And that’s problematic. Investors get hurt.”

Stranded 401(k) Investors

In many cases, these index funds came about as a way to round out a portfolio of funds made available in 401(k) menus, Johnson says. There’s a lot of inertia there, he says, given that plan sponsors might be reticent to change.

“As market shares have shifted in the 401(k) space, much of the money invested in them has been stranded,” Johnson writes. “These funds’ shareholders are left with what are effectively orphaned funds, which typically sport unreasonably high fees.”

In these cases, the individual plan participant often has no other choice if there aren’t lower-cost index options in the retirement program.

“This is unfortunately still a common problem,” MacKillop says. “A lot of the 401(k) plan sponsors have not done a very good job of screening the available investments for their plan participants.”

“Large firms are really preying on the ignorance of the plan sponsors in setting these things up, and there’s just a lot of payments that are way too high for the services being obtained.”

And for investors who are stranded in these funds over long-time horizons, those high fees could negatively impact their ability to reach their investment goals.

“Over time—over 20-25 years—a 2 percent difference is huge,” MacKillop says. “Depending on the size of your portfolio, that could be hundreds of thousands of dollars that you save for yourself over a long period of time. It’s not something people should be lazy about.”

Some Advantage?

MacKillop says there are things these sponsors could be doing differently that may justify slightly higher expenses. For instance, they could be replicating the index without buying all 500 stocks in the index. They may buy a representative sample, say 100 names or so, and this would save transaction costs. A lot of separately managed account products take that approach, he says.

They could argue that they have some sort of trading advantage. Dimensional Fund Advisors, for example, touts their trading skill.

But even so, he says, those advantages don’t justify the expense ratios these funds are charging.

“It’s almost impossible to imagine that Rydex would have a trading advantage over Vanguard, for example,” MacKillop says.

Investors Are Running the Other Way

The good news is these funds have been in structural decline for a number of years. The Rydex fund had net outflows of nearly $79 million in the last year and $304 million for the last five years ending Oct. 31. The top 10 worst offenders have lost nearly $1.5 billion in the last year. (See gallery.)

Morningstar’s Johnson believes these funds are a dying breed. But CFRA’s Rosenbluth says they’re likely to remain in place for far longer than they should, like The Walking Dead of the investment world. “I think they should die out,” he says. “I don’t think they will because some of the money that’s in these products is being ignored.”