By Chris Bryant

(Bloomberg Opinion) --Top corporate lawyers can take home millions of dollars a year, but until recently it was all but impossible for investors to share in the spoils — only a handful of U.K. and Australian law firms have gone public and U.S. practices are prohibited from doing so.

But finance didn't grow to become such a big slice of the economy by letting big pots of money escape its tentacles. The top 200 U.S. law firms generated about $110 billion in revenue last year, according to ALM Intelligence. Globally, a multiple of that figure is likely to have been paid out in damages. A tempting target.

Enter, litigation finance, companies like Burford Capital Ltd., IMF Bentham Ltd. or Vannin Capital that provide capital to a company or law firm to finance lawsuits in return for a share of any proceeds. Some will immediately question their social benefit: there's a potential conflict between money and justice being served, not to mention the possibly inflationary impact on the number and cost of lawsuits. For its part, the industry argues it gives access to justice and frees up funds for other purposes. (You can read a good overview of this debate from Bloomberg News’s Kit Chellel here.)

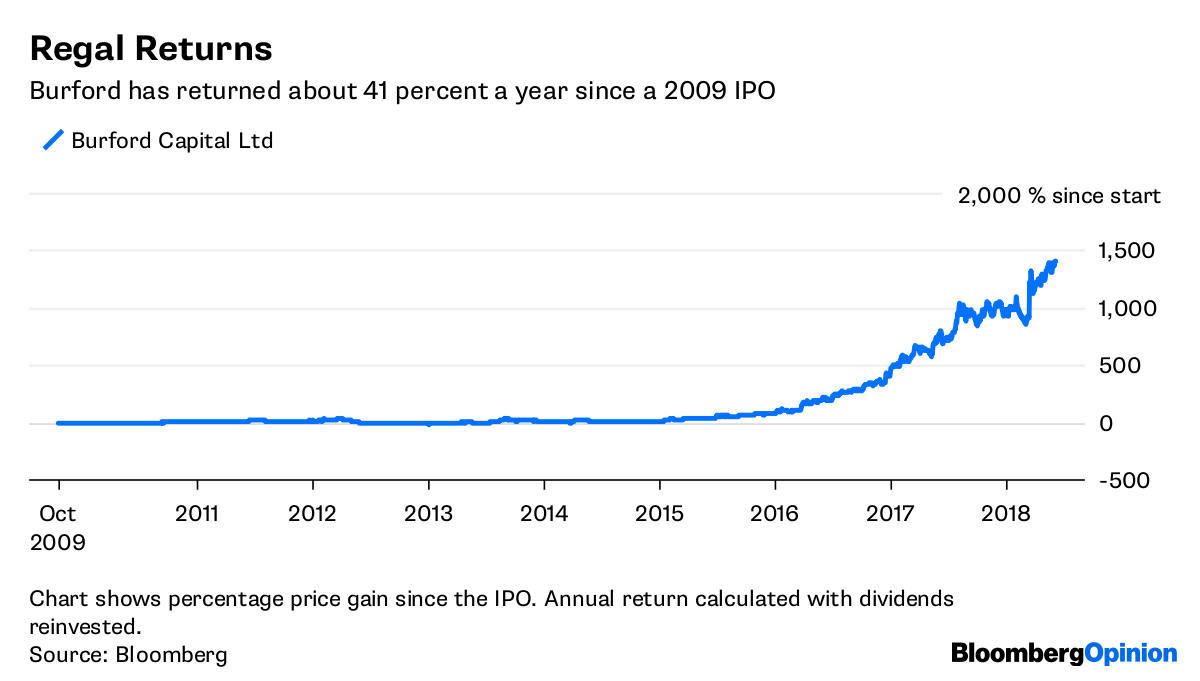

There’s no argument that the business can be enormously lucrative. Burford says the cases it has concluded so far have generated a 75 percent return on invested capital. Since going public on London's Alternative Investment Market in 2009, the stock has risen about 1,500 percent to value the company at 3.3 billion pounds ($4.4 billion) and make millionaires of lawyer founders Christopher Bogart and Jonathan Molot.

Yet Burford's finances are relatively opaque and valuing it is difficult. The company's strategy, at least, follows a script familiar to anyone acquainted with the financial services industry:

First, identify a big but illiquid asset class — lawsuits — whose returns are potentially very large and aren't correlated with the economic cycle.

Second, transform the risk profile of those win-lose lawsuits by spreading capital across scores of different cases, or by bundling several of a client's cases together.

Third, establish a secondary market to lock in some of the expected gains from a case, and allow reinvestment of capital, without having to wait for the appeals process to conclude.

Fourth, generate fee income from fund management to smooth out profits from inherently lumpy law cases. (Burford acquired a litigation funds business when it bought rival Gerchen Keller Capital LLC in 2016.)

Forecasting how much Burford will earn with much precision is all but impossible: litigation outcomes are inherently unpredictable, clients demand confidentiality and income typically stem from investments made years ago.

As with other financial firms, accounting rules oblige Burford to revalue its litigation assets based on progress made in those cases. In the legal world, those judgments are, by nature, somewhat subjective. About half of its reported litigation profits are so-called unrealized gains, which arise as a result of a positive court ruling or settlement offer. The related cash can take longer to turn up. Burford's auditors acknowledge inaccurate carrying values are a risk but say they test key assumptions and conduct their own external research.

Burford insists it takes a conservative approach to valuation and so far it has resisted the temptation to leverage up the balance sheet to juice returns on equity. And crucially, it's still been able to generate prodigious amounts of cash — even if a fifth of the individual cases Burford has financed turn about to be duds.

Burford's cushy position isn't impregnable. Burford’s profits will surely attract competition, driving down returns. Growth of the industry could also lead to regulation. If you want a guide to the future, look to the private equity industry, where firms are finding it hard to deploy the record amounts of capital they have amassed. Nothing — not even the most protracted lawsuit — lasts for ever.

To contact the author of this story: Chris Bryant at [email protected]

For more columns from Bloomberg View, visit bloomberg.com/view