Modern trusts1 continue to gain popularity as new trends develop. With the federal estate, gift and generation-skipping transfer (GST) tax exemptions now at $11.18 million up from the prior $5.49 million,2 it’s surprising that more clients haven’t elected to use these increased exemptions. We could see a tsunami similar to 2012 depending on whether future elections impact the exemption levels. The amount of U.S. households with $10 million or above in net worth is between 1.25 and 1.75 million so the market is more limited—approximately 1 percent of the U.S. population.3 Additionally, the number of millionaire households in the United States is approaching 15 million, which is about 12 percent of the U.S. population.4 There are approximately 7.2 million of these millionaire households with $1 million investable, which is 5.8 percent of the U.S. population.5 Some of these clients with net worths between $1 million and $11.18 million may need to decide whether income tax planning is more important than long-term intergenerational estate planning. Alternatively, they may desire to plan for both when possible. I’ll discuss some of these key planning strategies along with the associated issues and advantages.

Spring Delaware Tax Trap

There are many reasons to transfer assets intergenerationally into a long-term or perpetual trust with trust situs in a modern trust jurisdiction. Some of the key reasons are intergenerational federal death and GST tax savings, state death and income tax savings, asset protection, governance, privacy, preservation of family values, flexibility and control regarding investments and distributions.6 Despite these overwhelming advantages, many clients with net worths below the current exemption limit of $11.18 million may desire to intentionally spring the Delaware tax trap pursuant to Internal Revenue Code Section 2041(a)(3).7 This would in turn make an existing GST trust includible in the estate for income tax purposes so that the assets can receive a step-up in basis at death. It’s important to note that this strategy may not work in every state. Many of the states have rule against perpetuity (RAP) statutes that prevent this strategy.8

The Delaware tax trap deals with successive powers of appointment (POAs) if a state statute doesn’t require that a beneficial interest created by the exercise of a special POA must vest within a period beginning with the trust’s creation. The result is that the value of the trust principal could be included in the donee’s taxable gross estate as a result of the intentional springing of the Delaware tax trap. Generally, these states have abolished the RAP, have opt-outs or made it inapplicable to perpetual trusts.9 This can also generally apply to both common law RAP10 and Uniform Statutory RAP11 states. For example, say a parent establishes a perpetual trust in one of these states and creates a special POA in his daughter, Dorothy, in the year 2018. Subsequently, if in 2020, Dorothy exercises a special POA by creating in her child, Carolyn, another special POA, and the perpetuities period that governs Carolyn’s exercise of the power isn’t calculated from the date the trust was created (2018), the trust assets will be included in Dorothy’s federal gross estate pursuant to IRC Section 2041(a)(3). In some instances, the springing of the Delaware tax trap will result in giving a beneficiary the ability to take assets out of the trust while others will result in the assets remaining in trust, protecting them from the beneficiaries’ creditors. The Delaware tax trap may also be sprung by the creation of a presently exercisable general POA. Generally, use of the limited POA is preferred so that creditor protection can be maintained with the trust.

The springing of the Delaware tax trap generally won’t work in many of the perpetual trust states that have abolished the RAP and have codified the Murphy v. Commissioner case.12 These states have adopted a rule against the suspension of the power of alienation. This Murphy case approach, acquiesced by the Internal Revenue Service, eliminates possible problems with limited POAs for estate-planning purposes with perpetual trusts, which is very important to most wealthy clients. On the other hand, these Murphy case RAP statute states may be less advantageous to smaller estates looking to spring the Delaware tax trap from an income tax planning perspective.

Many other states have adopted long-term perpetuity periods13 without maintaining an alienation rule (that is, suspension of the power of alienation) so as to trigger the Delaware tax trap on the grant of successive POAs. The thought is that this approach provides a way of avoiding Section 2041(a)(3) by providing that a special power must be exercised within a very long period of years beginning at the creation of the trust based on the time period specified in the local statute. These are the term-of-years states. It’s also difficult to intentionally spring the Delaware tax trap with trusts in these states.

The decanting14 of a GST trust may also provide an alternative strategy to spring the Delaware tax trap. If a GST trust changes situs, it usually does so retaining the existing RAP provision of the original trust situs jurisdiction. Changing the RAP will generally be problematic. Also, the newly drafted trust to which the decant takes place usually adds limited POAs, thus providing added flexibility. These new trusts need to be carefully drafted with provisions to ensure that none of these new POAs may be exercised to extend the original RAP if they don’t desire to trigger the Delaware tax trap.

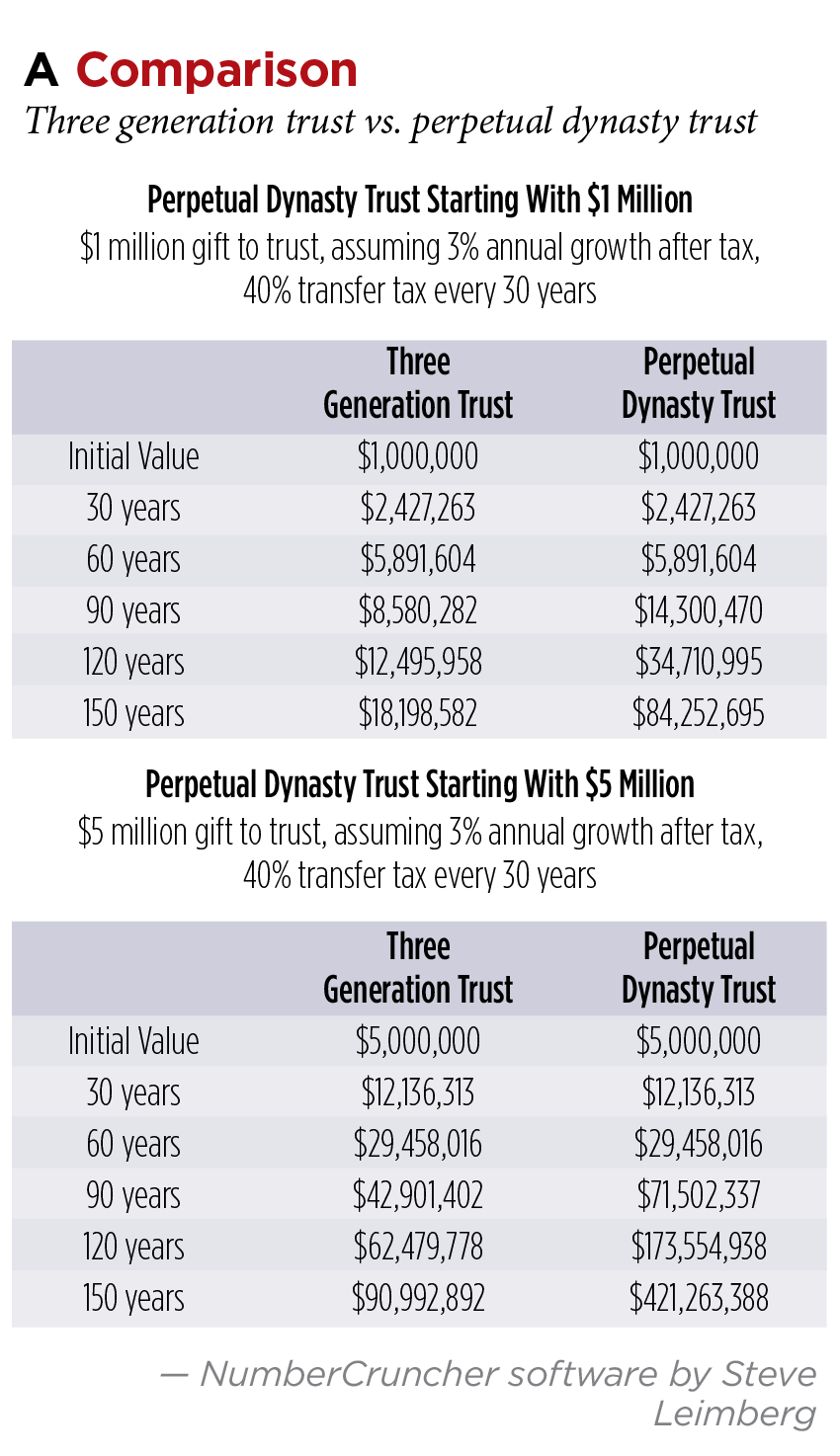

Consequently, the type of state RAP statute is very important in being able to spring the Delaware tax trap. This strategy is prohibited in Murphy case states15 and term RAP statute states16 but may be available in other states,17 thus providing for an income tax planning opportunity. This income tax planning opportunity may be short sighted. The trade off between income taxes and estate taxes is an important one. Clients should carefully weigh the importance of the GST tax exemption and how powerful it can be when used with long-term trusts or perpetual dynasty trusts before making income tax planning decisions such as springing the Delaware tax trap and including the GST trusts in their estate. Funds in a long-term or perpetual trust can provide powerful trust asset growth as well as all of the other previously mentioned benefits. The growth of a trust without federal and state death taxes and without state income and capital gains taxes is illustrated by “A Comparison,” this page, assuming $1 million and $5 million contributions respectively. Triggering the Delaware tax trap may eliminate this powerful growth opportunity of family trust assets as well as the creation of a family bank.

Swapping Assets

A preferred alternative to springing the Delaware tax trap with a GST trust may be the ability for a settlor of a grantor trust to buy back or otherwise swap assets tax free with the trust so that at his death, these assets receive a step-up in basis.18 This strategy combines all of the advantages of a long-term or perpetual dynasty trust with the ability to add income tax planning if desired. One popular example of this strategy involves the promissory note sale of a primary residence and/or vacation home to a defective grantor dynasty trust.19 One of the key advantages of this strategy is the ability to get the house back out of the trust to get a step-up in basis. This flexibility to get the house out of a trust doesn’t exist with a qualified personal residence trust (QPRT). Both of these trusts are grantor trusts and consequently allow the grantor to personally use any income tax advantages and planning allowed for personal residences. Additionally, the dynasty trust is a long-term or perpetual trust preserving the family home for several generations, while the QPRT isn’t a GST trust and thus not able to accomplish this objective.

Life Insurance

Another trend as a result of the high $11.18 gift, estate and GST tax exemptions deals with life insurance. Many states have creditor protection statutes protecting the cash value and/or death benefit of a life insurance policy. Some of the better state creditor protection statutes are Florida, New York and Texas. If a client isn’t in a state with a high creditor protection exemption for life insurance, he may consider using an irrevocable life insurance trust and/or a self-settled trust for the transfer or purchase of an insurance policy that should, if properly structured, fully protect the insurance policy.20 The exceptions to this trust protection include a fraudulent transfer, exception creditors and bankruptcy. These trusts, in addition to providing asset protection, may also provide an opportunity to garner lower state premium taxes.21 Limited liability companies (LLCs) may also be used,22 particularly with private placement life insurance (PPLI), to provide asset protection, access to cash value, low premium taxes and available solutions for dealing with the accredited investor rules.23 The LLC is generally included in the estate unless it’s owned by a trust that’s excluded from the estate.

Community Property Trusts

Another interesting income tax planning opportunity involves the conversion of joint property to community property via community property trusts.24 Many clients already live in community property jurisdictions, such as Arizona, California, Idaho, Louisiana, Nevada, New Mexico, Texas, Washington and Wisconsin. Alternatively, non-community property jurisdictions, such as Alaska, South Dakota and Tennessee, have enacted community property trust statutes that allow for assets transferred to a community property trust in one of these states to be designated as community property. Consequently, clients in non-community property states can transfer their joint property to a community property trust in Alaska, South Dakota or Tennessee and receive a 100 percent step-up in cost basis of assets held in the trust at the death of the first spouse. This assumes that the trust is properly drafted and administered in the community property trust state. This is in contrast to non-community property states with joint property, where at the death of the first spouse, the surviving spouse doesn’t receive a full step-up in cost basis. Instead, with joint property, the surviving spouse only receives a partial increase in cost basis. Therefore, only one-half of the joint property included in the gross estate pursuant to IRC Section 2040 would receive an IRC Section 1014 cost basis adjustment. There’s no basis adjustment of the other half. These trusts are generally includible in the gross estate.

PPLI25 is another popular trend and income tax planning opportunity that exists with trusts. PPLI is particularly popular with clients in high tax cities, such as New York City (12.86 percent), and high tax states, such as California (13.30 percent), Connecticut (6.99 percent), Minnesota (9.85 percent) and New Jersey (10.75 percent). PPLI is generally purchased to provide a tax-efficient wrapper for both traditional and sophisticated investments, such as publicly traded securities, alternative investments, hedge funds and private equity, many of which are tax inefficient. The modern PPLI policy provides an inexpensive tailored insurance wrapper for such investments, thus eliminating federal and state capital gains and income taxes on these PPLI cash value investments. The cost for a PPLI wrapper is typically between 70 basis points to 100 basis points. This is minimal compared to the high tax rates of many states. The tax savings are a key benefit particularly given the current high state income tax environment coupled with the reduction of the state and local income tax deduction by the recent tax reform. Further, if the PPLI isn’t structured as a modified endowment contract,26 then federal and state tax-free policy loans (that is, trust distributions) may also be made from the cash value of the policy. This is very advantageous to trust beneficiaries or even the grantors (if a self-settled trust, revocable trust or LLC is used) who reside in the high tax states. Consequently, zero tax dynasty trusts may be established, if funded by PPLI.

To acquire PPLI, many trustees will purchase insurance in a trust and/or LLC with situs in a modern trust state with low premium taxes27 and other favorable insurance laws.28 Insurance laws in certain low premium tax states also allow for in-kind distributions of cash value during life or with the death benefits, so if underlying assets are subject to an investment lock-up, there aren’t any issues. Additionally, as previously mentioned, the creditor asset protection of a life insurance policy owned by a trust and/or LLC may provide additional protection beyond the creditor protection provided by various state statutes if the policy is owned outright. Consequently, despite the high transfer tax exemptions, directed trusts and/or LLCs are usually the ideal choices for the purchase and administration of PPLI policies depending on a client’s goals and/or desires.

Endnotes

1. Typically, a directed perpetual or long-term dynasty trust in one of the favorable trust jurisdictions such as Alaska, Delaware, New Hampshire, Nevada, South Dakota and Wyoming. See Al W. King III, “Drafting Modern Trusts,” Trusts & Estates (December 2015).

2. Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017.

3. 2017 United States Net Worth Quantiles (using 2017 Federal Reserve Survey of Consumer Finance Data).

4. Ibid.

5. “The Kiplinger Letter” (Oct. 25, 2018).

6. See supra note 1.

7. Internal Revenue Code Section 2041(a)(3): “Creation of another power in certain cases—To the extent of any property with respect to which the decedent (A) by will, or (B) by a disposition which is of such nature that if it were a transfer of property owned by the decedent such property would be includible in the decedent’s gross estate under section 2035, 2036, or 2037, exercises a power of appointment created after October 21, 1942, by creating another power of appointment which under the applicable local law can be validly exercised so as to postpone the vesting of any estate or interest in such property, or suspend the absolute ownership or power of alienation of such property, for a period ascertainable without regard to the date of the creation of the first power.”

8. Robert J. Kolasa, “Problems in Springing the Delaware Tax Trap,” Trusts & Estates (April 2018); James M. Kane, “Income Tax Planning Using the Delaware Tax Trap,” LISI Estate Planning Newsletter #2295 (March 30, 2015); Lee Raatz “Delaware Tax Trap Opens Door to Higher Basis for Trust Assets,” Estate Planning (February 2014—Volume 41 Number 2).

9. For example, Arizona, Delaware, Hawaii, Illinois, Kentucky, Maine, Maryland, Michigan, Missouri, Nebraska, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Rhode Island, Virginia and Washington D.C.

10. For example, Iowa, Mississippi, Oklahoma, Texas and Vermont.

11. For example, Arkansas, California, Georgia, Indiana, Kansas, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Montana, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oregon South Carolina and West Virginia.

12. Idaho, New Hampshire, New Jersey, South Dakota, Wisconsin as well as North Carolina allow for a trust to last for unlimited duration relying on Estate of Murphy v. Commissioner, 71 T.C. 671 (1979), in which the Internal Revenue Service acquiesced to the method used to abolish the rule against perpetuities (RAP) by dealing with both the required “vesting” and “timing” issues associated with the RAP. In Murphy, the Tax Court held that the exercise of a limited power of appointment (POA) to create another limited POA didn’t spring the Delaware tax trap because under applicable Wisconsin law, the exercise of a limited POA didn’t commence a new perpetuities period. Wisconsin had a perpetuities statute expressed in terms of a rule against suspension of the power of alienation that limits the duration of a trust, rather than a rule based on the remoteness of vesting. This was accomplished by giving the trustee an implied or express power to sell assets that allows the trustees to jump outside the rule against suspension of alienation, thus creating an alternative vesting rule to avoid the vesting problem. Additionally, please note that the Idaho, South Dakota and Wisconsin unlimited duration statutes are pre-1986 and pre-date the modern generation-skipping transfer tax.

13. For example, Alabama (360 years), Alaska (1000-year limit with a limited POA), Colorado (1000 years), Florida (360 years), Nevada (365 years), Tennessee (360 years), Utah (1000 years), Washington (150 years) and Wyoming (1000 years).

14. There are currently 28 jurisdictions with decanting statutes. Generally, decanting is a discretionary distribution by a trustee of an older trust to a newly drafted trust. The power to decant derives from the trustee’s authority to distribute to one or more beneficiaries under the trust document, which is typically referred to as the “power to invade the trust.” However, with a decant, instead of distributing the trust corpus outright to a trust beneficiary, the trustee distributes or pours over the trust corpus to another trust. Al W. King III, “Decanting is a Popular Strategy but Don’t Ignore Several Key Considerations,” Trusts & Estates (August 2018).

15. See supra note 12.

16. See supra note 13.

17. See supra notes 10 and 11.

18. Generally, a grantor trust is a trust in which trust income is attributable to the grantor instead of the trust, thus the grantor pays the trust income tax instead of the trust. This is achieved by the grantor retaining certain powers under the trust that trigger the grantor trust status. If structured correctly, the trust wouldn’t be includible in the grantor’s estate.

19. See Al W. King III, “Trust Options for Residential Real Estate,” Trusts & Estates (December 2015).

20. See Al W. King III and Pierce H. McDowell III, “Selecting Modern Trust Structures Based on a Family’s Assets,” Trusts & Estates (August 2017).

21. Typically, a state premium tax is built into each insurance premium paid. The life insurance company pays this tax directly from the premium paid into the policy. Typically, the premium tax averages 200 basis points though the premium taxes vary dramatically among the states. The premium tax is generally based on the ownership of the policy. Please note that Alaska and South Dakota have two of the lowest state premium tax rates for both trusts and limited liability companies (LLCs). Delaware is one of the lowest for trusts.

22. For example, if a client has an existing trust in a high premium tax state and the client wishes to acquire private placement life insurance (PPLI) in a low premium tax state, a potential solution is for the client to form an LLC with a resident co-managing member in the low premium tax state. The resident co-managing member of the LLC in the low premium tax state can then purchase PPLI within the LLC and allocate the LLC units to the out-of-state trust, thereby allowing the existing out-of-state trust to benefit from the low state premium tax. Also, if the existing trust doesn’t qualify as an accredited investor who’s a qualified purchaser (for example, holds less than $5 million), then the grantor (assuming that individually the grantor qualifies as an accredited investor who’s a qualified purchaser) can form an LLC in a low premium tax state to take advantage of the low premiums.

23. Investors in PPLI must be “accredited investors” who are “qualified purchasers.” Under the accredited investor rules, natural persons must have a net worth of over $1 million, not including the value of the investor’s permanent residence or an annual income over $200,000 in the last two years. Generally, individuals or trusts who have at least $5 million in investment assets are considered qualified purchasers. See 115 U.S.C. Section 77(b)(15); 17 CFR Section 230.501(a); 15 U.S.C. Section 80a-2(a)(51).

24. See Terry N. Prendergast, “South Dakota Special Spousal Property Trusts: South Dakota ‘Steps-up’ to the Plate and Hits a Home Run for Surviving Spouses,” 61 S.D. L. Rev. 431, 432 (2016).

25. A PPLI policy is typically a privately issued variable universal life insurance policy that has both a cash value and death benefit component. PPLI is subject to the accredited investor and qualified purchaser requirements. Al W. King III and Pierce H. McDowell III, “Powerful Private Placement Life Insurance Strategies with Trusts,” Trusts & Estates (April 2016); Al W. King III and Pierce H. McDowell III, “State Premium Tax Planning?” Trusts & Estates (June 2011).

26. PPLI is usually designed as a non-modified endowment contract (non-MEC) policy that limits the amount of premiums that can be paid into it within the first seven years. Consequently, there are typically four to five premiums versus a single premium policy so as not to create a MEC. MEC policies (single premium) are subject to additional taxation of withdrawals and loans from policy cash value usually based on premium funding levels and timing of premium payouts. A non-MEC policy allows for tax-free withdrawals up to basis and tax-free loans against the balance of the account. Withdrawals in excess of basis are taxed as ordinary income, though a client can access the policy’s cash value without triggering a tax liability by taking a loan against the policy. Contrast with a MEC, in which accumulation within is tax-deferred, but withdrawals and loans are taxed as ordinary income first, and recovery of basis second. Consequently, the policy owner can only withdraw the initial premium tax-free after all of the accumulated gain has been withdrawn and taxed, so the policy owner can’t access the cash value in a tax-efficient manner.

27. Such as Alaska and South Dakota for both trusts and LLCs and Delaware for trusts.

28. See supra note 21.