Everyone seems to have his own definition of diversification. To some, portfolio diversification means investing outside of the usual suspects of public debt and equities. To others, it means exploring options beyond North American shores into Europe and Asia.

All of these definitions are correct, but they don’t go far enough. To me, expanding the notion of diversification is what is required. Anyone seeking impactful, true diversification should ask himself or herself one simple question. "Am I focused on risk or am I focused on rewards?"

Risk is the true diversifier. It is the most important factor one should consider when talking about true diversification. Investors make a huge mistake when they run from risk. Our industry tends to promote a returns based analysis. Using backwards looking models these spreadsheets convey the sense that somehow the past represents the future despite fine print that dispels that notion.

Diversified portfolios with an expanded allocation to a broader set of risk factors are generally better equipped to withstand periods of market drawdowns. And these portfolios should include investments whose volatility is connected to different factors of causation. In other words, focus on the causes of risks — not the outcomes — and allocate accordingly.

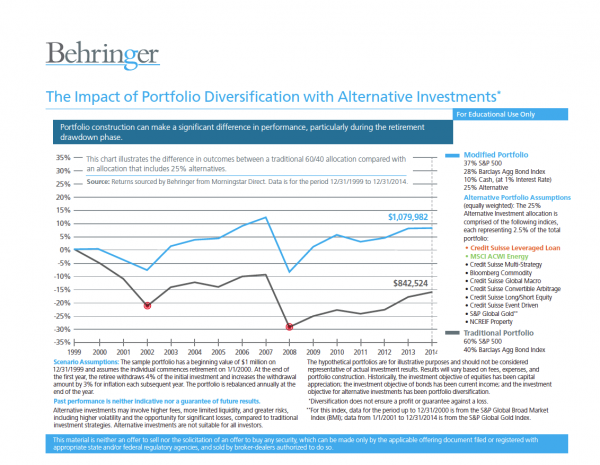

Market research shows that generally investors buy when the price is high and sell when the price is low. [1] For decades, financial experts have been preaching about staying the course during a market correction, but the research shows that (in the chart below) in a real or perceived crisis, many investors tend to ignore this advice.

Portfolios with traditional allocations of 60% stocks and 40% bonds

In a stylized Three Factor Model, style, capitalization and geography tend to manifest volatility well outside of what we know investors can actually tolerate. The data in this regard is as foundationally true as is the data that supports the 3 Factor model. Accepting one set of facts and ignoring the other is part of the problem.

The chart gives a retrospective view of how the addition of reduced-correlation asset classes can help dampen drawdowns. Note the grey line tracking performance over the last 14 years for a retiree that followed the standard model to construct a portfolio with 60% stocks and 40% bonds.

In 2002 and 2008, a retirement account with such a portfolio would have seen portfolio drops of more than 20% in both instances. After 14 years, the hypothetical investor would have had a decline in his remaining portfolio of nearly 16%, while annually withdrawing 4% of the principal. Worse yet, the probability that fear caused by this volatility would have prompted the investor to sell assets at a loss would have been quite high. Statistics during 2008 show massive net redemptions in equity funds and that is precisely the problem. [2] It’s a clear example of investors doing the wrong thing at the wrong time notwithstanding noble and well-intentioned arguments that investors should ignore their emotions.

Portfolios with a modified allocation of 37% stocks, 28% bonds, 25% alternatives and 10% cash

Consider another hypothetical portfolio with investments held for the same time period. Unlike the previous example, this portfolio includes additional asset classes and investment styles. As correlations tightened in traditional asset classes due to increased connectedness of a globalized world, this investor used an expanded definition of diversification to reduce their exposure to the volatile equities market by adding new asset classes and risk components while still challenging the portfolio to produce inflation-adjusted monthly income. With this approach, drawdowns in 2002 and 2008 would have been significantly muted, probably reducing the temptation to sell assets during these downturns. Reduced investment volatility would have reduced the probability that an investor would develop fear sufficient to sell at the wrong time. In addition, after 14 years, our hypothetical investor would have seen his portfolio increase in value, while still taking an annual 4% distribution, compared to the decrease in value of the traditional portfolio. [3]

Make no mistake, this portfolio is not optimized and certainly could be improved both in terms of allocation weightings and investment selections. Its simple point is to illustrate that adding new risk factors does actually help performance. This argument is not meant to refute the 3 Factor model but rather support it. This argument merely postulates that other factors exist as well and that even the attempt to add new risk factors to a portfolio may provide an enhanced diversification benefit which is vital for retirees most especially.

Reduce the potential of fear-based selling

An expanded application of diversification may temper volatility. It may also reduce the perception of risk that often prompts fear-based selling. The benefits of broadening the concept of diversification to include more risks are simple and clear. This technique of expanding the number of risks we expose portfolios may actually reduce volatility, and decrease the likelihood of fear-based selling during market downturns.

[1] Source: DALBAR’s 20th Annual Quantitative Analysis of Investor Behavior 2014.

[2] Source: Morningstar Direct

[3] Note: Past performance is neither indicative nor a guarantee of future results.

Frank Muller is Executive Vice President and Head of Distribution at Behringer