Retirement is getting a lot more expensive.

That’s the conclusion of a provocative new analysis by three respected retirement researchers. They conclude that a low-return outlook and rising longevity will require today’s workers to boost their savings by 40 percent or more to maintain their lifestyles in retirement. The same factors create challenges for today’s retirees relying on bond ladders or annuities for income.

The paper’s authors are David Blanchett, Morningstar’s head of retirement research, and Michael Finke and Wade Pfau, who both teach at The American College of Financial Services. They begin with the assumption that returns will be lower in the future than they have been historically. Noting today’s negative bond returns (net of asset management fees) and inflation, they suggest that planners should adjust their thinking accordingly with the rate of return assumptions in the models they use with clients.

“The international equity premium historically has been three to five percent,” says Blanchett. “So, if the long-term averages hold, we can’t expect returns to stay as high as they’ve been historically in the U.S.”

Longevity is the other factor driving up the cost of retirement. As I noted in a recent column for The New York Times, it is the most important factor determining retirement plan success and the most difficult to solve. Longevity for men and women at age 65 has jumped more than 10 percent since 2000, according to the Society of Actuaries. Men who reach age 65 can be expected to live to an average age of 86.6, and women to 88.8.

But those numbers are just averages—and higher-wealth households tend to beat the averages. Blanchett and his colleagues note that rising longevity—and very low real bond returns—have ratcheted up the cost of buying retirement income from annuity providers. They estimate the price of buying $1 in income via an inflation-adjusted annuity and find that the price of a dollar of safe income for a client retiring today is nearly 50 percent higher than it was in 2000.

The authors modeled the saving rates needed to maintain pre-retirement income using low, moderate and high rate-of-return environments. They found that a household that starts saving at age 25 would need total contribution values (employee and any employer contributions) of 4.3 percent for low earners and up to 9 percent for high earners, assuming historical rates of return. But in the low-return model, optimal saving rates range from 7 percent to 16.4 percent.

For households that start saving at age 35 or 40, the differences are larger. A single worker who starts saving at 35 would need a 14.3 percent rate in a high return environment, compared with 24 percent in a low-return scenario.

Blanchett acknowledges that high saving rates will be all but impossible for many workers. “But from my perspective,” he adds, “This is just saying people need to be saving more—and most households aren’t even close to where the numbers should be right now.”

Indeed, 28 percent of non-retired households with income greater than $100,000 said that they save more than 15 percent of their income, according to a 2015 survey by the Federal Reserve. Another 15 percent reported saving 11-15 percent and 24 percent said they save six to 10 percent.

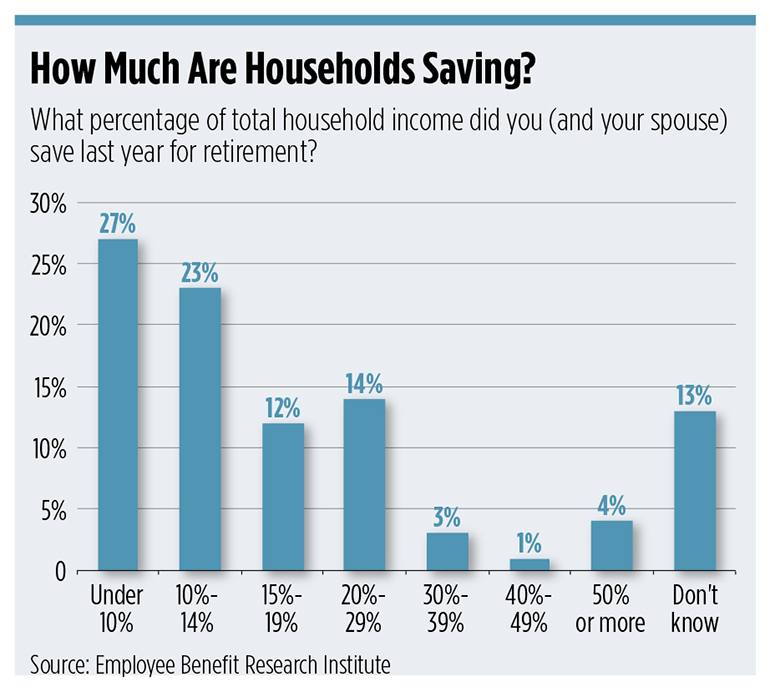

Looking only at saving for retirement, the annual Retirement Confidence Survey conducted by the Employee Benefit Research Institute finds that fully half save 14 percent of income or less, and 27 percent save less than 10 percent (see chart). At the same time, workers acknowledge that they should be saving more—17 percent say they need to save between 20 and 29 percent of their income and another 22 percent indicate they need to save 30 percent or more.

One hopeful sign: automation and behavioral nudge features added to defined benefit plans are improving saving patterns. Participation rates have risen sharply as a result of default auto-enrollment, especially among younger workers. Vanguard reports that 78 percent of workers age 25-34 participated in 2015, up from 68 percent in 2010 (the data is participant weighted).

Among defined contribution plans administered by Vanguard that used auto-enrollment, 48 percent defaulted workers into their plans at a three percent contribution rate, but the number of plans using higher rates is steadily ticking upward—for example, 11 percent started workers at five percent in 2015, up from just 10 percent in 2010. Most of the plans (69 percent) increase the rate automatically by one percentage point annually.

“The participation rates really have improved over the past ten years across the board,” says Jean Young, senior research analyst with the Vanguard Center for Investor Research. “You can see it in traditionally-designed plans, but it is really huge in plans that use auto-enrollment.”

For advisors working with clients, Blanchett advises a conservative approach. “Lots of advisors like to just use historical long-term averages because it’s easier and doesn’t require making any kind of forecast,” he says. “But clients do rely on you to tell how much to save, so your estimates need to be reasonable.”

Another finding from Blanchett and his co-authors that may surprise is that annuitization is a relatively more attractive option in the current low-rate environment—they find that the cost of building a bond ladder is greater than the increase in cost for an income annuity. “With a bond ladder, retirees spend principal and interest,” they write. “With an income annuity, retirees spend principal, interest and mortality credits, which are the subsidies from the short-lived to the long-lived. With interest low in both situations, the mortality credits become more important. Meanwhile, the low discount rate for the bond ladder makes it increasingly expensive, relatively speaking, to fund spending planned for the distant future.”

I’ll go one step further, and suggest this: If we want to encourage annuitization, why not get the job done by expanding Social Security—which is our most efficient annuity program?

61 percent of retirees rely on Social Security for at least half of their income, according to the Social Security Administration.

Expansion advocates argue for an across-the-board boost in benefits, with progressivity built in to avoid large increases to the wealthiest households.

Benefits could be expanded while simultaneously addressing Social Security’s projected long-term shortfall by eliminating the cap on payroll taxes for high-income workers, or at least raising it significantly (currently, no income over $127,200 is taxed). Other reasonable revenue ideas that have been floated include a very gradual increase in payroll tax rates over time, expansion of estate taxes and investing a small portion of the trust fund in stocks to boost returns (currently, reserves can be invested only in low-return Treasury notes).

Washington will get around to a debate about restoring Social Security’s financial balance at some point in the future. That is necessary, as the program’s retirement and disability trust funds are forecast to be depleted in 2034. At that point, benefits would be cut an estimated 21 percent, unless Congress takes action.

When they do, lawmakers should keep in mind the mounting challenges Americans face building for a secure retirement through savings alone.