One topic that too often receives inadequate attention from those working with individuals considering large charitable gifts is the challenge and planning opportunity that arises from the restrictive limitations on charitable deductions under our nation's income tax laws.

Under the terms of Internal Revenue Code Section 170(b), a taxpayer may deduct charitable gifts up to 50 percent of adjusted gross income (AGI) for gifts of cash to qualified organizations, 30 percent for gifts of non-cash appreciated assets and certain other gifts and 20 percent for gifts to private foundations (PFs) and certain other entities.

Unfortunately, when these limitations come into play, a donor can incur taxes on income that he didn't enjoy but he instead donated to one or more charities. In many instances, careful planning can reduce or eliminate what may be unintended negative societal impact caused by this IRC provision. Here's how.

Who's Affected?

Before examining ways to cope with this challenge, it can be helpful to point out which individuals are most likely to encounter these limitations.

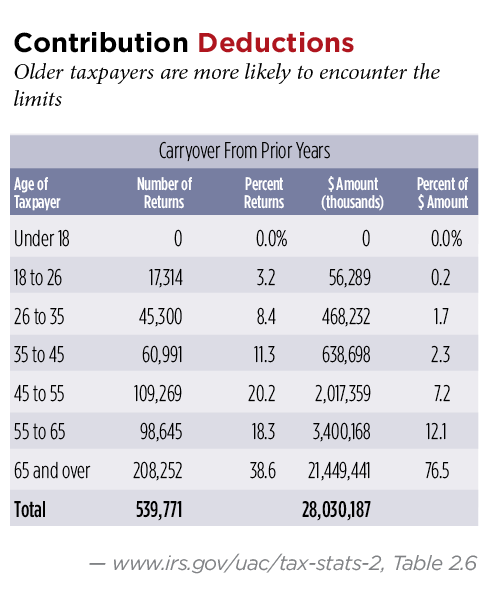

In 2013, the most recent year for which Internal Revenue Service statistics are available, some 539,000 taxpayers (more than the population of Omaha, Neb.) carried forward $28 billion in charitable deductions for gifts that were made in prior years.1 To put that amount in perspective, the total amount received by charities from estate gifts in 2013 was $24 billion.2 Further, just over $18 billion worth of securities were donated to charity in 2012, according to the IRS.3

It's also interesting to note that according to IRS figures, limitations on charitable gift deductions don't affect taxpayers across the board. In fact, as illlustrated in "Contribution Deductions," this page, in 2013, almost 39 percent of the taxpayers who encountered these limits were age 65 or older, with 77 percent of the dollars linked to that same age group. The numbers were almost 57 percent and 89 percent, respectively, for those age 55 or over.4

This age distribution can be explained to some extent by the fact that when individuals are retired, their AGI in comparison to their wealth may not be in the same alignment as it was during their working years when they may have had a higher income and less in terms of assets. Not surprisingly, the most recent IRS data indicates that gifts of securities and other noncash gifts are also disproportionately made by those age 65 or over. While just 20 percent of taxpayers who itemize are age 65 or over, some 51 percent of donors who itemized gifts of securities came from that age range.5 See "Securities Donors," this page. Those age 65 or over accounted for nearly 50 percent of the value of the donated securities (as indicated by the "Amount of Gifts" column in "Securities Donors").

As the 30 percent of AGI limitation applies to gifts of appreciated property, and a large portion of the asset base of many older individuals is held in this form, it becomes clear that much of the challenge in dealing with AGI limits on gifts of all types of property can come when working with clients in this age range who are contemplating larger gifts of cash and other assets.

Negative Effects of Limitation

Consider this example: A 75-year-old individual with assets totaling $10 million holds $5 million in the form of highly appreciated securities that yield annual dividends of $45,000. He also has $3 million in an individual retirement account from which he must withdraw $130,000 this year. His Social Security income is $30,000. In addition, he has $2 million invested in tax-exempt bonds that yield income of $45,000 a year.

This individual enjoys a gross income of $250,000. His AGI is just $200,000, however, after adjusting for his tax-exempt bond income and the portion of his Social Security income that isn't reportable.

Suppose he would like to make a gift of $360,000 in the form of appreciated securities to a capital campaign. This gift represents 3.6 percent of his wealth but over 150 percent of his AGI. In this situation, he would be allowed to deduct 30 percent of $200,000, or $60,000, in the year of the gift, and it would require that year and the entire 5-year carry forward period to fully deduct the gift.

On top of that, he won't be able to enjoy tax benefits from other gifts of securities made in the year of the gift or five future years and will see the amount he can give in the form of cash limited to 20 percent of his AGI during the same time period, as the combination of his cash and non-cash giving can't exceed 50 percent for any given year. Note that if he wants to make cash gifts of, say, $10,000 beyond his AGI limit during the limitation period triggered by the stock gift, it will require $15,000 pre-tax income to make such a gift, given his 33 percent marginal federal tax rate. This disparity is why philanthropically minded persons are sometimes advised under these circumstances to reduce or delay larger gifts they may have otherwise made.

This cap on giving unfortunately limits the amount of funds that might otherwise be available to fund America's social needs at a time when government spending is increasingly under pressure. Helping clients who face these limits plan effectively for them and minimize their impact can thus be of great value to taxpayers and the charitable entities they support. Fortunately, there are a number of ways to plan for AGI limits.

Spread Out Gifts

Perhaps the most obvious approach is to simply spread gifts out over several years. This strategy results in gifts still being made, even if their receipt by the charitable recipient is delayed.

Nonprofits have adjusted their fundraising approaches over the years to help accommodate AGI limitations, especially in the case of larger gifts. It's not uncommon for campaigns to allow pledge payment periods of five to seven years to help donors spread out their gifts in efforts to cope with limitations on their deductions and avoid the unfortunate situation in which they're forced to pay tax on amounts earned prior to their donation. I recently worked with a donor who won't begin to fulfill a $1.5 million pledge for six years and will then complete it over the following six-year period. This outcome was largely a result of a combination of cash flow issues and the need to plan for the 50 percent of AGI limit.

Modern practices that regularly allow the payment of large pledges over multi-year periods were undoubtedly influenced to some extent by the introduction of the charitable income tax deduction in 1917 and the limitations on the relatively restrictive 20 percent initial limit on amounts that could be deducted each year. In fact, historical evidence indicates that prior to the imposition of income taxes, donors were more likely to make gifts immediately and were even charged interest on unpaid pledges in some cases.6

Increase AGI

Another strategy is for a taxpayer to generate additional AGI in years when he wishes to make larger gifts. This may, in some cases, involve a sale of a portion of an appreciated asset and the donation of the remainder, a practice sometimes referred to as a "balanced sale." This strategy may come into play in a year when a client is selling a business or experiencing another significant income realization event. In other situations, a donor who's at or approaching retirement age may generate large gains in a year when he's rebalancing his investment portfolio.

Take Losses

In other cases, a client may decide to realize losses to offset gains and take advantage of other possible tax benefits. In this case, the taxpayer will have additional cash that can be used to make gifts that will be subject to 50 percent of AGI limits on gifts of cash rather than 30 percent limits for gifts of appreciated assets.

Voluntarily Forgo Deductions

It may also be advisable to take advantage of provisions in IRC Section 170 that allow a taxpayer to opt to take a deduction for the cost basis of an appreciated asset against the 50 percent of AGI limit rather than deduct its full value against the lower 30 percent of AGI limit. This can be a wise alternative when considering gifts of assets when there's been relatively limited appreciation.

Give Directly From an IRA

It may be prudent for individuals over the age of 70½ to make all or a portion of their gifts directly from a traditional or Roth IRA.

Funds donated in this way aren't reportable by the taxpayer, and donors are, in effect, allowed a 100 percent of AGI deduction for such gifts. That's because not reporting income is essentially the same as reporting that income before fully deducting it.

This strategy can allow those who would otherwise be subject to AGI limits to give up to an additional $100,000 per year on a tax-free basis.7 Keep in mind, also, that gifts made in this way in lieu of mandatory or other IRA withdrawals don't "swell" a taxpayer's AGI in ways that can limit other deductions or cause more of his Social Security income to be taxed. In the example outlined above, the taxpayer may have been better off making his $360,000 gift from his IRA to satisfy $100,000 of his mandatory withdrawals and complete his gift over a 4-year period rather than a 6-year period.

Planning for Larger Gifts

What about situations in which donors would like to make relatively larger charitable gifts over an extended period of time? And, suppose they also wish to provide for heirs on a tax-favored basis while they delay an inheritance for a period of time.

In this case, a wealthy couple with an AGI that's relatively low in comparison to their asset base may want to consider a charitable lead trust.8

Suppose, for example, a couple would like to give a total of at least $300,000 to charity each year for the foreseeable future, and their AGI is such that they'll never be able to deduct the bulk of those gifts. If they create a $5 million charitable lead annuity trust (CLAT) with a payout rate of 6 percent, this will generate the desired gifts to charity for 20 years while transferring assets to their children (who are in their late 20s) at a time when they wish them to receive the funds. No gift or estate tax will be paid on the amounts received by the children if the gift is completed assuming the June 2016 applicable federal midterm rate of 1.8 percent.

While donors may not retain the right to change where funds are directed from a trust each year without invalidating their CLAT, they may wish to create a donor-advised fund (DAF) and name the DAF to receive the annual CLAT payments and thereby indirectly influence where the funds are distributed to each year. They may also opt to use the funds to fund a PF over time.

From an AGI standpoint, the results are similar to a gift directed from an IRA because the funds distributed from a CLAT don't flow through the donor's taxable income. Again, this result is tantamount to receipt of the income followed by a 100 percent deduction of those funds.

There's nothing abusive about this plan, as it simply reflects the fact that the donors have irrevocably given up ownership of the underlying assets and are directing that a flow of funds go to charity for a period of time in lieu of an immediate gift of the underlying assets to their heirs.

A Blended Gift

For a client who wishes to make a significant gift as part of her long-term estate and financial planning, but also would like to retain an income for life or other period of time, a charitable remainder trust can offer another alternative when planning for AGI limitations.

Assume, for example, the client decides to fund a charitable remainder unitrust (CRUT) or a charitable remainder annuity trust (CRAT). At the time she funds the trust, she directs that a portion of the income each year be distributed directly to one or more charities she wishes to support over an extended period of time (or to a DAF as described in the example of the CLAT above).

Suppose she uses highly appreciated, low yielding securities to fund a $2 million CRUT making annual payments of 5 percent and specifies in the trust that

20 percent of the annual payments be made to her favorite charity each year. In the first year, the charity will receive $20,000 from the anticipated $100,000 payment, and the donor receives $80,000, some four times the $20,000 of dividends she was receiving from the securities used to fund the trust. She is, in effect, giving the charity a portion of the income each year generated by assets in the trust that would have otherwise been consumed by capital gains taxes had she sold the securities.

The payment amount being shared can fluctuate each year in the case of a CRUT or be fixed for the duration of the trust in the case of a CRAT.

As in the case of the CLAT and the IRA distribution, that amount doesn't flow through the client's taxable income each year and is therefore not subject to AGI limitations. This gift thus functions as a practical hybrid CLAT and CRUT, what I sometimes refer to as a "Lunitrust."

Need for Change

Charitable deduction AGI limits were designed from the outset in 19179 to allow taxpayers to voluntarily direct some, but not all, of their income to charitable purposes without being subject to income tax on those amounts.

Given this nearly century-old policy, Congress should carefully consider the limits that already exist on charitable gifts in terms of AGI when deciding how to account for charitable gifts as part of ongoing tax reform deliberations. Congress should take into account that many taxpayers, especially retirees, already encounter significant limitations on how much they can give, and further limitations would be even more destructive in terms of revenue already foregone each year by America's non-profit community.

The law as currently set out doesn't adequately address the fact that many people have large amounts of donatable assets that yield little income and distorts their ability to make charitable gifts without first paying tax on the donated amounts.

Congress should also differentiate between mortgage interest and certain other deductions that help individuals build their personal wealth and the charitable deduction that's designed to reflect the fact that many selfless individuals are willing to voluntarily forego personal income in favor of gifts to fund societal needs. The charitable deduction isn't a "loophole;" it's in reality an integral part of the intricately woven fabric of a civil society.

While legislators contemplate the future of the charitable deduction and the extent to which it should or shouldn't be limited, the suggestions outlined in this article can serve to help the most generous among us to make significant gifts without being penalized by a tax policy that many question the wisdom of, as these individuals are simply trying to make the largest gifts they can afford given the assets and income at their disposal.

Endnotes

1. Table 2.6, "Returns with Itemized Deductions: Sources of Income, Adjustments, Itemized Deductions by Type, Exemptions, and Tax Items by Age, Tax Year 2013," www.irs.gov/uac/tax-stats-2.

2. Giving USA 2014 (summary of giving for 2013), www.givingusa.org/insights/.

3. Internal Revenue Service Statistics of Income Bulletin, Spring 2015.

4. See supra note 1.

5. Supra note 3.

6. Thomas W. Goodspeed, A History of the University of Chicago (1916), at p. 70.

7. Internal Revenue Code Section 408(d)(8).

8. Ashlea Ebeling, "Precision Wealth Transfer With A CLAT," Forbes (Dec. 10, 2014).

9. "Topics in Wall Street," The New York Times (July 12, 1917).