With investors worried about rising interest rates, bond funds sank in May and June. The declines were severe for exchange traded funds and closed-end funds. Some municipal ETFs dropped to discounts of 2 percent of their asset values, while closed-end bond funds fell even further. Seeing the discounts, you could be tempted to invest. After all, it is often attractive to buy when a dollar’s worth of assets sells for 98 cents or less. But discounts can be misleading. While some of the closed-end funds represented bargains, the ETFs were not necessarily on sale.

“The fact that an ETF trades at a 2 percent discount can be irrelevant,” says Paul Baiocchi, an analyst for IndexUniverse.com.

To appreciate the varying meanings of discounts, it is important to understand that ETFs and closed-end funds have different structures. As a result, the funds don’t always move in lockstep. Shares of closed-end funds regularly swing up and down sharply, while ETFs are more stable.

Closed-End Fund Volatility

Like conventional mutual funds, closed-ends invest in portfolios of stocks and bonds. Trading on stock exchanges, the shares can sell at premiums during bull markets and slip to discounts in hard times. Many advisors urge clients to buy the funds at discounts and avoid them when shares command premiums. The volatility of closed-ends was on display during the rough bond markets of the past year. With investors desperate for income—and not worried about rising interest rates, many closed-end funds moved to substantial premiums in the fall of 2012. Then this year, the pendulum swung. AllianceBernstein National Municipal Income (AFB) followed a typical path. Last September the closed-end fund commanded an 8.1 percent premium. But by May this year, the fund had shifted to a discount of 4.3 percent.

While all closed-end funds can be volatile, municipal funds can be especially erratic, says John Cole Scott, portfolio manager of Closed-End Fund Advisors. Scott says that nearly all municipal closed-end funds are owned by retail investors who seek income. Most institutions stay away because they have no need for tax-free dividends. When they crave yields, the unsophisticated closed-end shareholders bid up prices to unrealistic levels. At the first sign of trouble, the investors bolt. Most bond closed-ends trade in small daily trading volumes of less than $5 million, says Scott. “It does not take a lot of trading to push the shares up or down,” he says.

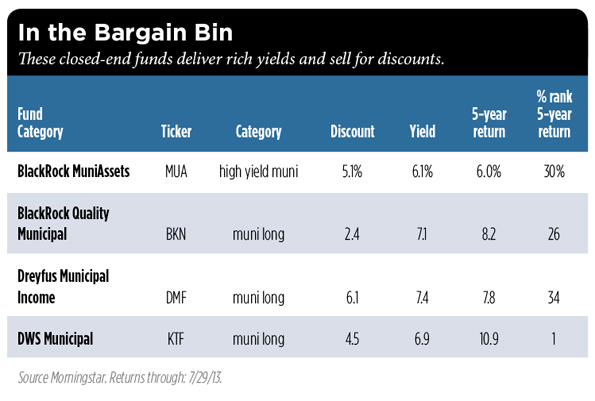

Scott recommends BlackRock MuniAssets (MUA), which sells for a discount of 5.1 percent and pays a tax-free yield of 6.2 percent. While BlackRock keeps most of its assets in investment-grade bonds, the fund increases the yield by holding some issues that are rated below-investment grade.

Sizable closed-end discounts can persist for months. That provides time for contrarian investors to take positions. On July 23, the average municipal closed-end fund had a discount of 6.3 percent, according to Cecilia Gondor, executive vice president of Thomas J. Herzfeld Advisors, which specializes in closed-end funds. Some funds traded at double-digit discounts and paid tax-free yields of more than 6 percent. The discounts could remain for awhile because of the uncertainty created by the bankruptcy of Detroit, says Gondor. But she says that the discounts will narrow eventually. “The yields are so attractive that investors will come back,” she says.

Part of the reason for the discounts is that most closed-end bond funds use leverage. In a typical approach, a fund will issue debt worth about 30 percent of the value of the portfolio. The borrowing is used to finance more investments for the portfolio. In good times, the leverage magnifies gains, but it increases losses in downturns. Wary investors have been reacting to the possibility of future problems.

The ETF Bargain Bin

While closed-end funds periodically trade at sizable discounts, ETF shares only hit big discounts during moments of extreme stress, such as the turmoil of 2008. ETFs are relatively placid because of the way that new shares are created. Say that an institutional investor wants to put $10 million into an ETF that tracks the S&P 500. The institution places the order with a broker known as an authorized participant. The broker takes the client’s cash and buys shares of the 500 stocks in the index. The stocks are then given to the ETF in exchange for shares in the fund. When the institution wants to make a withdrawal, the broker exchanges the ETF shares for the shares of the 500 stocks. If the ETF slipped to a 1 percent discount, an institution could immediately swap its discounted ETF shares for the shares of the 500 stocks. In effect, the investor would be trading an asset worth about 99 cents for something worth a dollar. Such arbitrage can result in profits and help to eliminate discounts.

Because of the arbitrage, broad stock ETFs rarely trade at sizable discounts or premiums. But ETFs that hold relatively illiquid assets—such as municipal bonds—can hit discounts in harsh times. For municipal funds, the problems appear because many tax-free issues rarely trade. The bonds are owned by retail investors and institutions that stash the securities away and hold them until they mature. Since there is no daily trading, an ETF portfolio manager must hire an outside firm to estimate prices to determine the fund’s net asset value.

While the estimates are produced once a day, traders buy and sell the ETFs constantly. During market downturns, the estimates may not adjust fast enough to keep up with changing market conditions. Discounts appear when the share prices drop more rapidly than the estimates fall. “In general, industry participants feel that the share prices provide a fair value of the bonds in the portfolios,” says Timothy Strauts, a senior fund analyst for Morningstar.

The ETF discounts tend to melt away as markets calm and estimates of values catch up with trading realities. In May, iShares S&P National AMT-Free Municipal Bond (MUB) posted a 1.3 percent discount. By July, the discount had faded to 0.8 percent. For long-term holders, the appearance of the discount was not a significant event. Those speculators who seek out such discounted ETFs are not likely to produce any windfall profits.