On Nov. 2, 2017, the House Ways and Means Committee issued H.R.1 called “Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.” Here’s a review of the provisions that affect estate planning professionals.

Transfer Tax Changes

The federal estate, gift and generation-skipping transfer tax exemption immediately increases by $5 million. The exact amount of the new exemption amount could be $11.2 million (or just under $11 million), depending upon how inflation adjustments are calculated. A married couple can transfer $22.4 million dollars gift, estate and GST tax free with the use of inter vivos planning or portability. A mere .02 percent of taxpayers paid estate tax before the Act. With the increase in the exemption, the percentage will be lower. Likely less than 1,000 estate tax returns will be filed per year with a tax due if the Act becomes law.

- Permanent repeal of the estate and GST taxes in 2024. However, this is subject to the risk that a future administration may repeal it or that the taxes are readopted later. Under Internal Revenue Code Section 2611, the term “generation-skipping transfer” includes a taxable distribution, a taxable termination and a direct skip. In other words, upon repeal of the GST tax, after Dec. 31, 2023, for any trusts to which GST exemption hadn’t been previously allocated, distributions could be made to “skip persons” without incurring a GST tax. What happens to assets already transferred to trusts that aren’t already exempt from GST taxes? Would taxpayers be able to make distributions to skip persons without triggering a GST tax? It would seem so.

- Retention of the gift tax on gifts over the exemption amount made after Dec. 31, 2023 with a top tax rate of 35 percent. Additionally, with the increased exemption to $11.2 million under the proposal, practitioners should consider whether transfers should be made from any trusts to which GST exemption hadn’t been allocated to take advantage of the additional exemption amount. To the extent that these transfers are made from trusts that had been previously funded, no additional transfer tax would be incurred. To maximize the potential for this strategy of taking advantage of the increased GST exemption, practitioners should consider whether distributions may be made from non-exempt trusts to GST trusts. While there had been some speculation as to whether the gift tax would be retained when candidate Trump made his initial recommendations as to the transfer tax system, the Act appears to confirm what most advisors thought, that the gift tax will remain intact.

- Assets held by the decedent may still obtain a step-up in basis to its value on the date of death, as under current law.

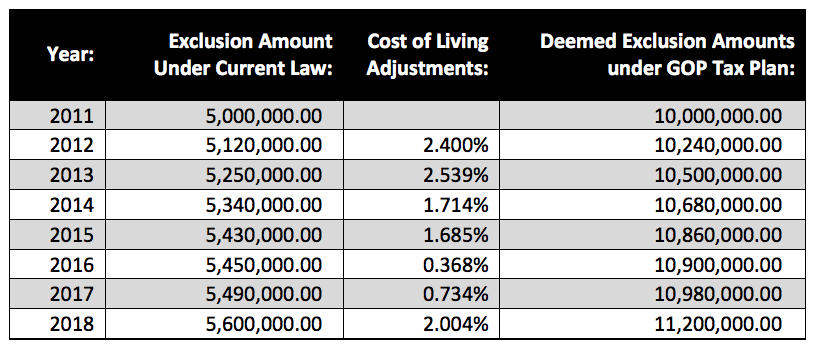

Transfer Tax Exemption

The proposal changes the basic exclusion amount as set forth in IRC Section 2010(c)(3)(A) from $5 million to $10 million. The effect of this change is that the exclusion is deemed to have increased per Section 2010(c)(B) each year by cost-of-living adjustments so that, assuming the law is enacted and becomes effective as of Jan. 1, 2018, the exclusion amount appears it will be $11.2 million based on the following table:

Qualified Domestic Trusts and Non-Citizen Spouses

Under current law, the estate tax is imposed upon any distributions made from a qualified domestic trust to the surviving spouse and on the value remaining in the QDT on the death of the surviving spouse. The Act will eliminate these taxes:

- For any QDT created on or before Dec. 31, 2023, there will be no tax on distributions made to the surviving spouse after the 10th anniversary of the creation of the QDT. If the surviving spouse dies after Dec. 31, 2023, there will be no tax on the value remaining in the QDT.

- For any QDT created after Dec. 31, 2023, distributions won’t be taxable, and the value remaining in trust won’t be subject to the estate tax.

If the Act Becomes Law

With the doubling of the exemption amounts, clients have an opportunity to accomplish significant gifting after the effective date of the Act. Connecticut residents who might face a state gift tax for transfers over $2 million should exercise caution. Assuming that repeal of the estate tax will be temporary or never become effective, making gifts will enable these clients to remove further assets from their taxable estates and exempt any future appreciation from transfer taxation. Further, with no assurance that a future administration will not only negate the repeal of the estate and GST, but also might lower the exemption amounts, planning shouldn’t be deferred for wealthy clients. Will there be a clawback if there’s a future change of excess exemption? While that hopefully won’t occur, practitioners might caution clients making new exemption gifts of this possible risk. As to what level of wealth is appropriate to plan for will depend on various factors.

- Certainly, if asset protection or other non-estate tax benefits might alone be worthwhile, the new exemption should be used as soon as feasible.

- Those clients with estates over $10 million to $12 million should consider using the new exemption. As the level of net worth increases, the incentive to proactively plan should increase.

- Large estates should use the increased exemption, if enacted.

- Clients who’ve previously consummated note sale transactions should consider immediately funding additional gifts to the purchasing trusts to shore up the economics of those sale transactions. If the practitioner subscribes to the mythical 10 percent seed gift theory, an additional $5 million gift (perhaps $10 million with gift splitting, and perhaps more if the inflation adjustment in fact applies) can support an additional $90 million to $100 million of the sale transaction (depending on whether the practitioner subscribes to the 9:1 or 10:1 application of this construct). On those transactions, consider evaluating the need for the existing guarantees. On much larger transactions, the additional trust “capital” might be supportive, but have no meaningful impact on guarantees. On smaller note sale transactions, that additional $5 million gift might be used to pay off a portion or all of a note, thereby eliminating the IRC Section 2036 string argument as to the note.

- Evaluate powers of appointment and related planning. If, for example, a client created a trust and named a not-so-wealthy elderly relative to have a general POA over the trust, or even more so if a client had considered such planning but didn’t proceed because of the size of the relative’s estate, the increased exemption available next year to that relative might be enabled using a general POA to obtain a large basis step-up on that relative’s demise for the client’s asset in that trust. This is precisely the type of basis planning that one wonders about if those scoring the tax consequences to the federal fisc in the summary addressed.

What clients might be willing to do with respect to planning, and how practitioners approach and advise different clients, will in part depend on how far client planning has progressed.

How to Plan Now

Apart from the tax issues, those who haven’t completed, or even started, meaningful planning should nonetheless act now. Estate planning should never be only about estate taxes. For most people, more wealth is dissipated from elder financial abuse, lawsuits, divorce, spendthrift heirs and other risks than from estate taxes. Properly crafted modern trusts can address all of these concerns and provide more flexibility no matter what results from the Act. Given that the tax laws are still in flux, the best course is to infuse flexibility into plans. The Act defers repeal until 2024, leaving open the possibility of unfavorable changes by a future administration. By way of example, married clients should consider forming non-reciprocal, spousal lifetime access trusts called SLATs to which gifts or sales transfers might be made. Single clients might consider self-settled domestic asset protection trusts called DAPTs, or hybrid DAPTs (a dynastic trust that has a mechanism to add the settlor back as a beneficiary so that the trust at inception isn’t a DAPT).

Example 1: Client started a plan to create two non-reciprocal SLATs in late 2016 out of concern about adverse tax changes, but put the planning on hold after Trump was elected. The client should evaluate whether additional gifts may be made to these trusts after enactment of the Act to take advantage of the higher exemption amounts. So long as the gifts contemplated to each trust are under the exemption amount, this planning might be viewed as having no downside gift tax risk and there should be no reason not to complete the planning. The non-tax benefits of the structure, such as asset protection and divorce protection, also remain.

Example 2: Client is quite concerned about malpractice suits. The estate includes significant holdings in an investment limited liability company and has a value of approximately $20 million. The client’s attorney drafted non-reciprocal SLATs to which the clients contemplated gifts of discountable assets. Part of the motivation is asset protection planning. While the need to secure those discounts might appear academic considering the significant increase in exemption amounts, the clients will assuredly benefit from the asset protection benefits of irrevocable trusts regardless of whether there are estate and gift tax benefits. If the plan hasn’t yet been implemented, the trusts might be modified to incorporate additional flexibility, for example, naming a non-fiduciary to add the grantors back as beneficiaries in the event of premature death of one spouse. Perhaps the level of transfers might be reduced somewhat to lessen the gift tax exposure until more is known about future tax legislation. However, if the client resides in a decoupled state, perhaps the planning should continue unabated. Another option might be to amend and restate the LLC operating agreement to negate discounts.

Example 3: Client whose net worth is about $8 million owns a valuable building held in an LLC. The client shifted $2 million worth of the LLC interests to a irrevocable DAPT to secure discounts. The client is quite old and infirm and is domiciled in a non-DAPT decoupled state. Now that we know the repeal of the estate tax won’t happen until 2024 (if at all), the planning might need to be modified. Because the estate tax exemption could be more than $11 million when the client passes—and because all the assets owned by the client at death will be eligible for a basis step-up—it might be advisable for the client to retain sufficient incidents of ownership so that the assets may be includible in his estate. Depending on the risks of asset depletion, the practitioner may wish to consider whether it would be advisable to prepare an action by the trust protector now to move the situs and governing law of the trust to the client’s non-DAPT home state to cause estate inclusion.

Example 4: Client owns a large family business. The family is involved in a complex note sale (installment sale to a grantor trust) transaction that involves several tiers of transactions. Should the plan be abandoned? Likely not. Safeguarding and preserving the family business is the major goal. Leaving stock in the family business exposed to possible transfer, remarriage or creditor risks wouldn’t be prudent, nor would that be acceptable to the family. Stock that’s held in an irrevocable trust that isn’t GST tax exempt might be better protected in a dynastic trust. To the extent that the transaction has progressed reasonably far down the planning continuum, and regardless of the outcome of the estate tax repeal, it may be advantageous to have the family business stock shifted to the dynastic GST tax exempt trust. The risk of death before repeal in 2024 is a concern. While the risk of a worsening estate tax environment isn’t as material as when planning began, the efforts and cost to complete the transaction are worthwhile when weighed against the potential benefits to be gained and are insignificant relative to the value of the business. Most importantly, the family has no confidence that even if the Act becomes law in its current form or some modified version, a future administration won’t overturn the estate tax repeal.

With the possibility of repeal on the horizon, avoiding a gift tax remains paramount. Because the fate of the Act is uncertain, the following planning remains worth considering regardless of whether or in what form the Act is enacted:

- Annual exclusion gifts.

- Gifts of the exemption amounts including the possible increased (double) exemption that the Act might make available in 2018.

- Grantor retained annuity trusts that can have an automatic adjustment mechanism.

- Note sales using defined value mechanisms. The type and application of the defined value mechanism should be considered in light of the IRS’ continued attack on such techniques. True v. Comm’r, Tax Court Docket Nos. 21896-16 and 21897-16 (petitions filed Oct. 11, 2016).

- New life insurance should favor flexible policies to facilitate adjustment to new developments. For example, it might be advantageous to consider policies that build a cash value so that there’s an exit strategy if the policy is no longer needed.

- Additionally, with the Act’s increased exemption to $11.2 million under the proposal, practitioners should consider whether transfers should be made from any trusts to which GST tax exemption hadn’t been allocated to take advantage of the additional exemption amount. To the extent that these transfers are made from trusts that had been previously funded, no additional transfer tax would be incurred. To maximize the potential for taking advantage of the increased GST tax exemption, practitioners should consider whether distributions may be made from non-exempt trusts to GST trusts. For taxpayers with estates of a size where there’s no need to preserve the new GST tax exemption, it might be prudent to make late allocation of GST tax exemptions to existing trusts so that if a future administration rolls back the Act’s benefits, those trusts will already be exempt (barring some type of clawback).

Example 5: Client has a $25 million dollar estate and has made no taxable gifts. She gifts $5 million of marketable securities to a self-settled trust in 2017, and plans to make another $5 million gift in 2018 if the Act's increased exemption becomes law. This is very low or no risk in terms of gift tax. There are no valuation issues, and the gift is below the client’s exemption. The practitioner may wish to encourage the client to gift more to the trust to take advantage of the higher exemption. What if a new administration repeals the Act in 2020? Might there be a clawback of amounts gifted?

Example 6: Clients have a $30 million dollar estate, $10 million of which is comprised of an LLC that owns marketable securities and $10 million of which is a real estate LLC that owns commercial rental property. They have not made any prior taxable gifts. Wife gifts $5 million of discounted membership interests in the marketable securities LLC to a SLAT. Thirty days later, she sells $5 million of discounted interests to the SLAT. Is this likely to be minimal risk in terms of gift tax exposure? There are potential valuation issues, so some type of valuation mechanism might be appropriate. But given the remaining exemption she’s preserved in 2017, would the Wandry approach suffice? Since the Act’s version of estate tax repeal doesn’t include repeal of the gift tax, what will happen to these planning structures? If the client is audited and faces an audit adjustment, the gift tax exposure on that audit may have been for naught because if the client had waited, the repeal of the estate tax may have obviated the need for planning. Should this planning be pursued? Does a Wandry clause make the transaction lower risk? What if a different type of defined value mechanism were used instead? Does lowering the discount rates lower the risk profile of the plan? Would it be more advantageous to wait until 2018 and make a gift of perhaps $8 million when the exemption may be $11.2 million? The reality is that determining the risk profile of any transaction is quite subjective, fact sensitive and will vary as each practitioner weighs these factors.

Unintended Consequences

Because the Act is certain to face significant opposition, even if some variation of the Act becomes law, estate tax repeal may not extend past the next few election cycles. Nonetheless, practitioners should consider alerting clients of the possible unintended consequences and planning considerations that might result from proposed repeal of the estate tax:

- Practitioners might encourage all clients to revisit testamentary and revocable trust dispositive schemes. In particular, how might language in existing documents be interpreted under the Act? Might the client’s intended dispositive plan be disrupted? Even if uncertainty abounds, might it be advisable in some instances to take a precautionary stance and revise documents now? If existing documents make a bequest of an amount equal to the exemption amount, how might the doubling of the exemption amount in 2018 affect the distributions under those existing documents should the Act become law?

- If a client has a long-term GRAT or note sale transaction in place, the contractual obligations to continue payments may or may not be affected by the repeal. If a court-ordered modification is obtainable, such as the GRAT no longer serves its purpose, will that trigger a gift tax by the inception of the transfer if the gift tax isn’t repealed? Will the result differ if the gift tax is repealed? What about the fiduciary duty of the trustee? Would a court even permit the modification of an irrevocable trust that’s valid under state law because of a post-funding change in tax law? For existing note sales, making an additional gift of the increased exemption might facilitate, in smaller note sale transactions, repaying the note and concluding the transaction.

State Estate Tax Systems

What will the impact of the many provisions of the Act be on different states? Evaluating the impact of the state income tax issues and loss of state and local tax deductions could be devastating for higher tax states. State income tax rate could be 40 percent higher for wealthy taxpayers in higher tax states so that 39.6 percent maximum federal rate + 3.8 percent net investment income tax of a deduction will be lost. In other words, a higher federal tax is paid on state income tax. This might result in state income and property taxes pressuring wealthier people to move their residences to states without income tax and with lower property taxes. Might we see a migration to low or no income tax states?

What will this do to state budgets? There could be a dramatic shift in tax burdens. There could be dramatic difference in how different people are affected by the interplay of all these changes.

What’s the interplay of the Act’s $10 million inflation adjusted exemption and state estate tax systems? What about the New York estate tax cliff? Under New York law, if an estate slightly exceeds the exemption amount, the exemption is lost, and the entire tax is incurred on the entire estate. While a higher exemption amount would obviate the issue for many New Yorkers, the magnitude of the cliff will create an incredibly costly penalty for moderate wealthy clients who only modestly exceed the exemption. In 2019, the New York estate tax exemption is supposed to equal the federal one. Will it be $10 million, or will New York be forced to amend its estate tax law to maintain its revenue base? How will other states react? Only about 14 states have independent state estate tax. How will this affect them? What will states with estate tax systems do if the Act becomes law? Will they retain their estate taxes? Will it be cost-effective with a $10 million inflation adjusted exemption amount for a state that parallels the federal estate tax to retain an estate tax? Will non-decoupled states feel an increased pressure to repeal their estate tax system if so few residents will be subject to tax?

Portability

With recent leniency provided by the Internal Revenue Service on filing late portability elections, will clients be willing to incur any cost with the prospect of the exemption doubling? (Rev. Proc. 2017-34, Internal Revenue Bulletin: 2017-26, dated June 26, 2017.) In the future, will clients even be willing to listen to recommendations to file a federal estate tax return if the exemption is doubled? Certainly, fewer moderately wealthy clients may be willing to do so. For those clients affected, in the event that the estate tax is reinstated as expected, loss of portability from failure to file an estate tax return on the death of the first spouse can create greater estate tax on the death of the survivor.

Those taxpayers with portable exemptions from a prior deceased spouse might consider using those exemptions before a future administration may negatively affect them. This could take the form of using that deceased spouse’s unused exemption to fund a DAPT. By using a DAPT, the client may not be prevented from accessing the wealth transferred. So, if a future administration negatively affects the portable exemption, it will have already been used.

Non-Tax Estate Planning

More moderately wealthy clients may choose simplistic outright bequests if there’s no tax incentive. The term “moderate” may again be redefined relative to the new doubled exemption amounts. Practitioners will have to educate clients as to the obvious benefits of continued trust planning, such as divorce and asset protection benefits. In the absence of any transfer taxes, this may become the primary goal for many trust plans. With increased longevity, the likelihood of remarriage following the death of a prior spouse will increase. The need for trusts on the first death to protect those assets may be more important than many realize.

While trusts may afford tax planning opportunities by sprinkling income to whichever beneficiary is in the lowest income tax bracket, will the lower income tax brackets provided under the Act reduce this benefit sufficiently enough to mitigate against this use of trusts? The distributions carry out income under the distributable net income rules of IRC Sections 651-652 and 661-662. Might it make more sense for trusts to make non-interest-bearing loans to beneficiaries to repay mortgages, the interest on which is no longer deductible under the new Act?

Trust planning may also be modified to reflect the potential repeal of the estate tax:

- Discretionary trust distribution standards should replace mandatory income distribution standards because these won’t be required to qualify for qualified terminable interest property requirements under IRC Sections 2056(b)(7) and 2523(f).

- Consider including POAs so that assets can be revested in the grantor (or another person) if it proves advantageous under the new post-repeal planning rules to obtain a basis step-up. The provisions should permit inclusion but not mandate or force inclusion.

- How might practitioners contemplate a repeal of the repeal, or the reinstatement of an estate tax, in drafting new documents? With so much uncertainty, is it even advisable to endeavor to anticipate reinstatement in documents? What might be done with a tax apportionment clause for documents anticipating a future reinstatement of an estate tax? This situation is similar to what practitioners considered as 2010 approached with the law providing for no estate tax in that year. Practitioners had to construct their documents to say, in effect, “I leave my assets this way if there is an estate tax in effect when I die, but that way if there is none.” This will require careful thought in structuring and drafting. And, as indicated above, even if the estate tax is repealed, the repeal may be cancelled before the 2024 date, if not earlier, by a change in the White House and the Congress.

- Because the estate tax might be reinstated, planning that removes assets from the client’s estate (with the powers to cause inclusion if that proves advantageous) might protect the family from the estate tax if it comes back in the future.

Wealthy taxpayers should consider undertaking arrangements that have low gift and income tax risk and low cost and significance non-estate tax benefits such as asset protection and income tax shifting. Ultra-high-net-worth clients should proceed with planning because the deferral of repeal until 2024 doesn’t appear to provide sufficient certainty to ignore planning. These options, including an installment sale to a grantor trust or a GRAT as described above, are two of many that can be implemented. Obviously, these will work best to remove assets from an estate tax system if the assets perform well from a financial viewpoint. Consider creating these arrangements under the laws of a domestic asset protection state so the grantor may be able to continue to enjoy them if desirable.